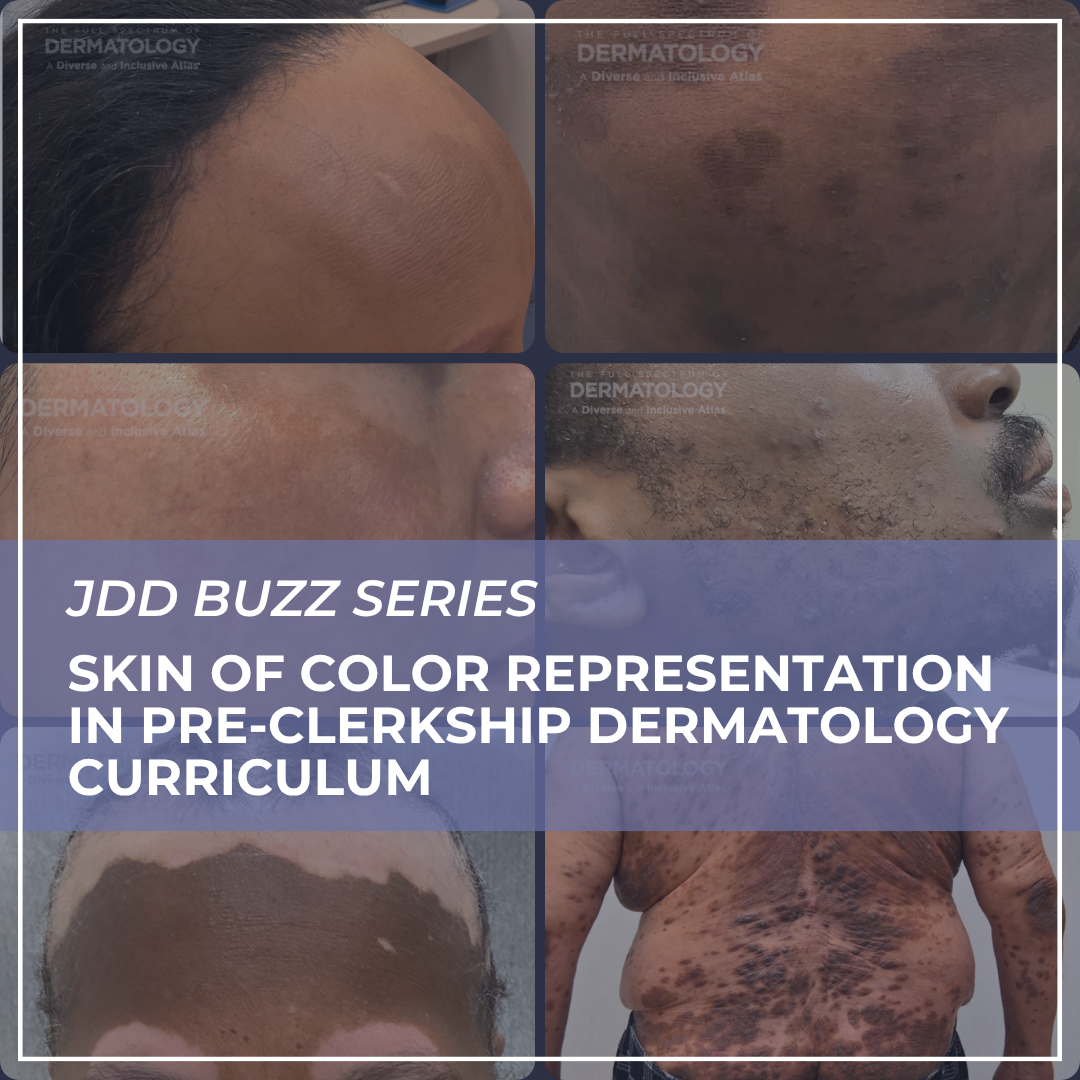

Medical school dermatology curriculum is known for its lack of representation of images of skin of color. A letter to the editor published in the July Journal of Drugs in Dermatology shows the effects on diagnostic accuracy, perception, and confidence when one medical school took action to make its pre-clerkship dermatology curriculum more diverse.

I interviewed authors Dahyeon (Esther) Kim, a fourth year medical student, and Janiene Luke, MD, professor of dermatology and dermatology residency program director at Loma Linda University School of Medicine.

What led Loma Linda University School of Medicine to make its pre-clerkship dermatology curriculum more diverse?

At Loma Linda University School of Medicine, we began to reevaluate our dermatology curriculum in response to consistent student feedback that highlighted a lack of diversity in the skin tones represented during pre-clerkship teaching. This concern aligned with broader national discussions and growing academic literature on the underrepresentation of skin of color in dermatologic education. As accurate diagnosis is often dependent on pattern recognition in dermatology and that must be trained across the full spectrum of skin tones and racial/ethnic backgrounds, this prompted a focused initiative to improve the inclusivity of our curriculum.

What specific changes did the School of Medicine make?

We invited a dermatology faculty member with expertise in skin of color to lead critical portions of the curriculum redesign. Our first priority was to ensure that foundational principles, such as dermatologic terminology, morphology, and the basic science of skin diseases were clearly covered. From there, we emphasized the importance of exposing students to a wide range of dermatologic conditions across all skin tones. We recognized the limitations in current educational resources: many conditions have few, if any, high-quality images available in darker skin tones. We also deliberately included patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds in addition to skin type. Additionally, we aimed to dismantle implicit biases often reinforced in medical education, such as the disproportionate portrayal of sexually transmitted infections in darker skin types.

After the restructuring, your team found medical students scored higher on diagnosing conditions presented in patients with skin of color than the previous cohort. Did that surprise you?

The improvement in diagnostic accuracy among students taught under the revised curriculum was encouraging but not unexpected. Our hypothesis was that increased skin of color representation would result in improved diagnostic competency, and the data validated this assumption. We were mindful of potential confounders—such as differences in clinical exposure between upperclassmen (previous cohort) and underclassmen—yet found that underclassmen outperformed their senior counterparts specifically on skin of color images. Interestingly, diagnostic performance for lighter skin tones remained comparable between cohorts. This suggested that the revised curriculum had a targeted effect in improving diagnostic ability in areas where representation was historically lacking.

Your findings did show that diagnostic accuracy in skin of color is still lacking in comparison to diagnostic accuracy in lighter skin tones. What can be done to reduce diagnostic disparities?

Despite the improvements, we still observed a 10-15% disparity in diagnostic accuracy between skin of color and lighter skin tones. To close this gap, we advocate for a multipronged approach. First, we must increase the number and quality of clinical images representing dermatologic conditions across a wide range of skin tones and ethnic backgrounds. Unfortunately, the lack of available skin of color images remains a widespread issue, underscoring the need for national collaboration in image database development. Equally important is the critical examination of content for implicit bias, ensuring that we avoid perpetuating stereotypes that could harm patient trust or skew diagnostic reasoning. Lastly, examining the curriculum and increasing the proportion of skin of color images to facilitate pattern recognition would be helpful in reducing disparities.

What are some other key takeaways from your study?

A central takeaway is that students are not passive recipients of medical school curricula—they are aware of the diversity, or lack thereof, in their educational materials and view representation as integral to their training. In our study, students overwhelmingly reported that improved skin of color representation would enhance their ability to care for diverse patient populations. Interestingly, though, increased exposure did not translate into increased confidence, suggesting that more immersive, longitudinal experiences may be necessary to build both diagnostic accuracy and clinical assurance. Additionally, our findings highlight the importance of integrating feedback from our learners to continuously evolve the curriculum in a way that alleviates both educational and societal disparities.

How should medical schools and residency programs apply these findings?

Medical schools and residency programs should take an active role in assessing whether their curricula proportionally reflect the diverse patients and communities they serve. Although there is no established guideline on what proportion of dermatologic images should be of skin of color, demographic trends provide useful benchmarks. For instance, non-Hispanic whites made up 62.2% of the U.S. population in 2014 but are projected to comprise only 43.6 % by 2060, according to U.S. Census data.1 In our own curriculum, skin of color image representation increased from 16% to 23% after revision—an improvement, but still short of being demographically reflective. To bridge this gap, institutions may consider restructuring the curriculum to be more reflective of the current demographics, implementing skin of color-focused workshops, increasing student access to platforms with robust skin of color image libraries, and offering clinical rotations at skin of color clinics, if available, to strengthen both knowledge and confidence.

What else should dermatology clinicians know about increasing skin of color representation in medical school dermatology curriculums?

It is important for dermatology clinicians to understand that increasing skin of color representation in medical school dermatology curricula is but one aspect in the overall schema for improving dermatologic care in patients of color. Other key aspects are diversifying the dermatology workforce, providing adequate training in skin of color during residency, and conducting research in diverse populations. Utilizing a comprehensive approach such as this will help to decrease healthcare disparities, improve patient outcomes, and allow patients to receive dermatologic care that is culturally responsive.

Source:

-

- Colby, Sandra L. and Jennifer M. Ortman, Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060, Current Population Reports, P25-1143, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2014.

Did you enjoy this JDD Buzz article? You can find more here.