Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare, neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by rapidly enlarging, painful ulcers with violaceous and undermined borders. It is commonly associated with systemic disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, hematologic malignancies, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).¹ While PG often correlates with IBD flares, its pathogenesis is not well understood. Colectomy has been used to treat severe PG, suggesting a link between PG and bowel inflammation.² However, rare reports of PG developing after colectomy and ileostomy, with ulcers at peristomal sites, indicate that PG can occur independently of active bowel disease.³ Here, JDD authors present a case of PG that occurred one year after total colectomy for ulcerative colitis (UC). The PG was successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone and systemic adalimumab. This case supports the observation that PG can manifest independently of bowel disease activity.

Case Presentation

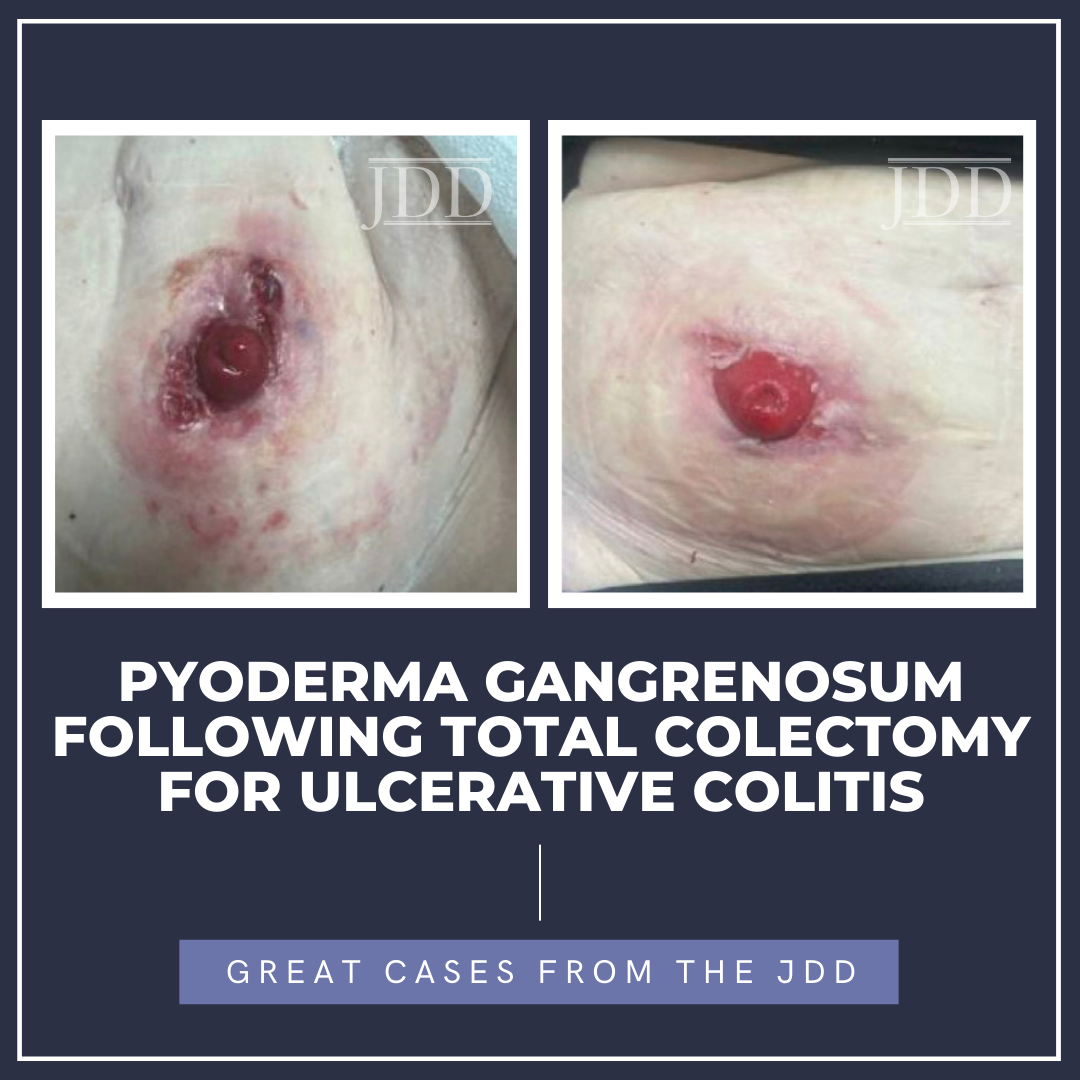

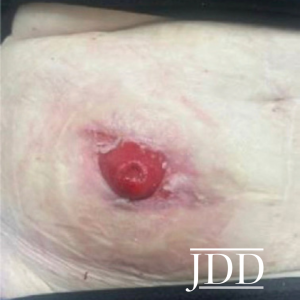

A 55-year-old woman presented with painful ulcerations near her ostomy site one year after undergoing a total colectomy for UC. Her history of UC had been associated with severe refractory diarrhea, fecal incontinence, weight loss, and abdominal pain despite treatment with mesalamine and risankizumab. She also had recurrent Clostridium difficile infections, sepsis requiring fecal transplantation, and a prior sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis with abscess formation. Due to worsening UC despite medical therapy, she underwent total colectomy and ileostomy. Approximately nine months postoperatively, the patient reported pain and irritation around the ostomy site. She was diagnosed with a chronic intraabdominal abscess and underwent drainage on the medial aspect of the ileostomy. Four months later, the patient developed multiple large cribriform ulcers with undermined borders and surrounding erythema surrounding a clean ostomy (Figure 1). Due to increasing pain, history of UC, undermined borders, cribriform appearance, and progression of ulcerations, peristomal PG was suspected. The patient was initially treated with intralesional triamcinolone injections (10 mg/mL x 1 mL) across two visits. Due to the progression of lesions, systemic adalimumab was initiated (160 mg loading dose, followed by 80 mg, then 40 mg every two weeks). Over the following month, her ulcers significantly improved, decreasing from three lesions to a single small ulcer (Figure 2).

erythematous patches around the ostomy site on the lower R abdomen.

and intralesional corticosteroids.

Discussion

This case underscores that PG can occur independently of UC disease activity, even after complete removal of the colon. The pathophysiology of PG post-colectomy likely reflects immune dysregulation despite the absence of active bowel disease, including excessive neutrophil recruitment and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8, IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-36.1,4 Colectomy may also induce intestinal dysbiosis and disrupt immune tolerance by eliminating gut-associated lymphoid tissue, which promotes the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and regulatory T-cells.5 This disruption can alter the gut-skin axis and promote immune-related skin diseases such as PG.5 Pathergy, an exaggerated inflammatory response to minor trauma, is implicated in up to 50% of PG cases and likely also contributes to the development of PG post-colectomy at ostomy sites.¹ Historically, systemic corticosteroids were the primary therapy for PG, but their prolonged use is associated with significant adverse effects. Biologic agents such as TNF-α inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in PG and are increasingly used. This case provides further evidence that PG can develop after colectomy and in the absence of intestinal inflammation. PG should be in the differential diagnosis for IBD patients who develop ulcerations near peristomal sites, even if they occur after colectomy. Further studies are needed to better understand the relationship between bowel activity and PG pathogenesis.

References

1. Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(3):191-211. doi:10.2165/11595240-000000000-00000

2. Talansky AL, Meyers S, Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD. Does intestinal resection heal the pyoderma gangrenosum of inflammatory bowel disease? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;5(3):207-210. doi:10.1097/00004836-198306000- 00002

3. Holmlund DE, Wählby L. Pyoderma gangrenosum after colectomy for inflammatory bowel disease. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1987;153(1):73- 74.

4. Guénin SH, Khattri S, Lebwohl MG. Spesolimab use in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;34:18-22. doi:10.1016/j. jdcr.2023.01.022

5. Sinha S, Lin G, Ferenczi K. The skin microbiome and the gut-skin axis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39(5):829-839. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.021

SOURCE

Lau, Charles B., and Mark Lebwohl. “Pyoderma Gangrenosum Following Total Colectomy for Ulcerative Colitis.” Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD 24.12 (2025): 1254-1255.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this JDD case report? You can find more here.