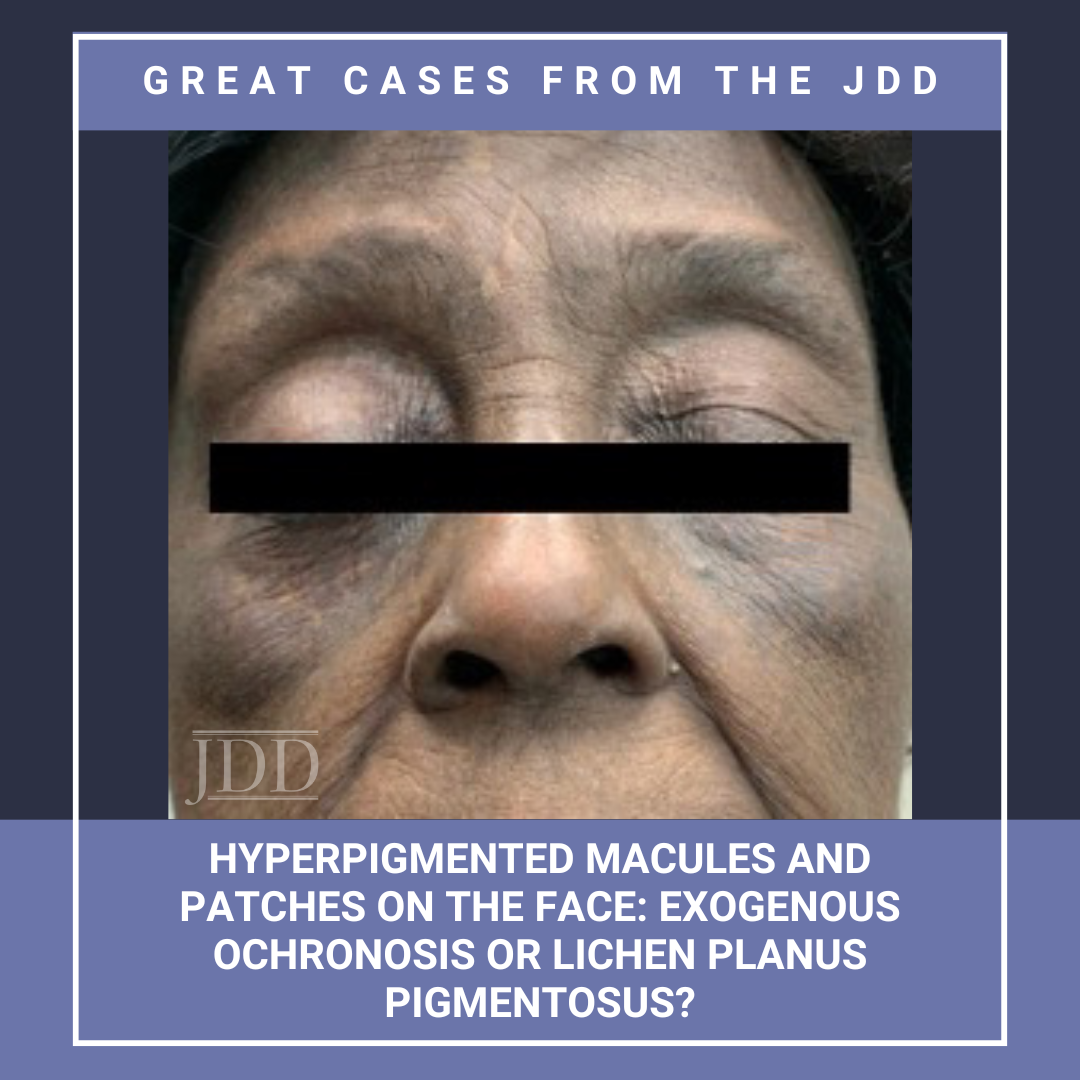

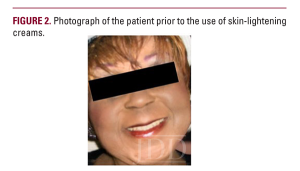

JDD authors Deepika Narayanan, MD and Stephen K. Tyring, MD, PhD, MBA present a case of a patient with a 10-year history of blue-black macules and patches on the face and an associated history of skin- lightening cream usage. The skin lightening cream contained hydroquinone, which is often associated with exogenous ochronosis (EO). Interestingly, the biopsy did not show characteristic findings of ochronosis, confusing the final diagnosis; however, discontinuing the skin-lightening creams halted the progression of the patient’s skin lesions supporting a diagnosis of EO. EO presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation after using products containing hydroquinone. This condition is most common in Black populations, likely due to the increased use of skin care products and bleaching cream containing hydroquinone in these populations. Topical hydroquinone is FDA-approved to treat melasma, chloasma, freckles, senile lentigines, and hyperpigmentation and is available by prescription only in the US and Canada. However, with the increased use of skin-lightening creams in certain populations, it is important for dermatologists to accurately recognize the clinical features of exogenous ochronosis to differentiate it from similar dermatoses. An earlier diagnosis can prevent the progression to severe presentations with papules and nodules. The authors summarize the clinical presentations diagnostic features, and treatment pearls, concluding with a discussion of the differential diagnoses.

Introduction

Exogenous ochronosis (EO) is a common skin condition that presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation after using products containing hydroquinone. Other causative agents include resorcinol, phenol, mercury, picric acid, and antimalarials such as quinine. Hydroquinone in concentrations above 4% and treatment courses as short as 3 months may be associated with EO.1 We present the case of a patient with a classic history of hydroquinone use with contradicting biopsy findings.

Case Report

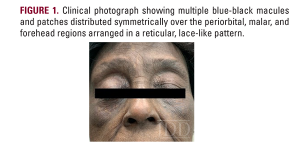

A 79-year-old Black woman presented with a 10-year history of blue-black macules and patches on the face. She had no notable medical history. Cutaneous examination revealed multiple blue-black macules and patches distributed symmetrically over the periorbital, malar, and forehead regions (Figure 1). The lesions were arranged in a reticular, lace-like pattern. No other sites were involved, and systemic examination was normal.

Discussion

EO can mimic other skin conditions, as seen in this case. LPP may mimic EO with gray-brown hyperpigmentation in sun-exposed areas in people with darker skin. LPP is often preceded by a pruritic phase which indicates activity and progression of disease. Furthermore, topical hydroquinone can be utilized as a treatment for LPP in conjunction with tacrolimus ointment. Melasma can appear similarly to OE on sun-exposed areas of the face and is also more common in women with darker skin types. Melasma clinically presents as tan, evenly pigmented macules symmetrically distributed on the face. However, pigment deposition is usually epidermal. On dermoscopy, melasma appears as a reticular pattern accentuation of normal pseudo-rete, dark-brown granules and globules with follicular sparing.4 Patients with melasma are often prescribed skin-lightening agents with hydroquinone, which may lead to the development of EO in patients with pre-existing melasma. Argyria presents as blue-gray discoloration of the skin, including mucosa and sclera, from the deposition of silver within the skin. Involvement of the mucosa and gingivae and associated neurological deficits may help differentiate argyria from EO.

Conclusion

References

-

- Levin CY, Maibach H. Exogenous ochronosis: an update on clinical features, causative agents and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2(4):213-217.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Exogenous ochronosis associated with hydroquinone: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(6):675-684.

- Findlay GH, Morrison JG, Simson IW. Exogenous ochronosis and pigmented colloid milium from hydroquinone bleaching creams. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93(6):613-622.

- Dogliotti M, Leibowitz M. Granulomatous ochronosis: a cosmetic-induced skin disorder in blacks. S Afr Med J. 1979;56(19):757-760.

- Simmons BJ, Griffith RD, Bray FN, et al. Exogenous ochronosis: a comprehensive review of the diagnosis, epidemiology, causes, and treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:205-212.

- Brenner M, Hearing VJ. Modifying skin pigmentation: approaches through intrinsic biochemistry and exogenous agents. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2008;5(2):e189-e199.

Source

Narayanan, Deepika, and Stephen K. Tyring. “Hyperpigmented Macules and Patches on the Face: Exogenous Ochronosis or Lichen Planus Pigmentosus?.” Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD 23.7 (2024): 567-568.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this JDD case report? You can find more here.