Vulvar dermatoses are commonly underdiagnosed in women with skin of color, and culture plays a role. Certain communities of color view vulvar concerns with shame or as evidence of moral impurity, leading women to delay seeking care. Structural and educational barriers can also influence how a woman obtains medical care for her vulvar concerns and even what she shares with the clinician. In addition, gaps in research and clinical education have further enhanced underdiagnosis and undertreatment. A poster presented at Skin of Color Update sought to investigate these barriers and their impact, and envision a new way forward for equitable vulvar care.

I interviewed the poster’s lead author, Grace Herrick of the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine.

What led you to want to investigate barriers to the recognition of vulvar dermatoses in women with skin of color?

Our interest developed from noticing how limited the research is on vulvar dermatoses in women with skin of color and how consistently the literature points to diagnostic gaps, delayed recognition, and underrepresentation. As we began studying vulvar conditions more closely, it became clear that most of the clinical frameworks, educational images, and diagnostic descriptions are based almost entirely on lighter skin tones. This creates an obvious question: What happens to patients whose skin does not match the images clinicians are trained to recognize? The more we explored the literature, the more striking the disparities became. Women of color are almost absent from vulvar treatment studies, textbooks rarely include images of vulvar disease in darker skin, and multiple papers describe systemic delays that are linked to stigma, medical mistrust, and structural inequities. The evidence made it clear that there is a meaningful blind spot in both research and clinical education, motivating us to investigate the barriers that shape diagnosis in this population. Our goal was to understand the cultural and systemic factors that contribute to under recognition and to emphasize why an inclusive, culturally informed approach to genital dermatology is necessary for equitable care.

How did you conduct your review?

We conducted a narrative review using PubMed, Google Scholar, and leading dermatology and gynecology journals. Our search included terms such as vulvar dermatoses, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, vulvar disease in skin of color, cultural stigma, health disparities, and medical mistrust. We focused on peer-reviewed studies, clinical guidelines, and recent reviews that identified epidemiology, diagnostic challenges, patient-provider communication, and structural barriers to care. Since the published literature specific to women with skin of color remains limited, we also investigated related fields such as sexual and reproductive health, health communication, and disparities in research to better understand the cultural and systemic factors contributing to delayed diagnosis and inequitable care.

What were your most surprising findings?

One of the most notable findings of our review was the extent to which cultural stigma and internalized shame shape women’s ability to recognize vulvar symptoms, communicate concerns, and seek timely evaluation. The degree of diagnostic delay was alarming. Lichen sclerosus alone demonstrates an average delay of over 16 months, with even longer delays and higher rates of misdiagnosis in children with skin of color. Additionally, we were surprised by how limited educational resources remain for clinicians. Most training materials continue to center around lighter skin tones, which makes it challenging to identify inflammation, early scarring, or dyspigmentation in darker skin. The lack of clinical trial studies and epidemiologic data inclusive of people with skin of color limits the development of equitable and evidence-based care.

What are some of the cultural and systemic barriers to vulvar care? How does shame impact care?

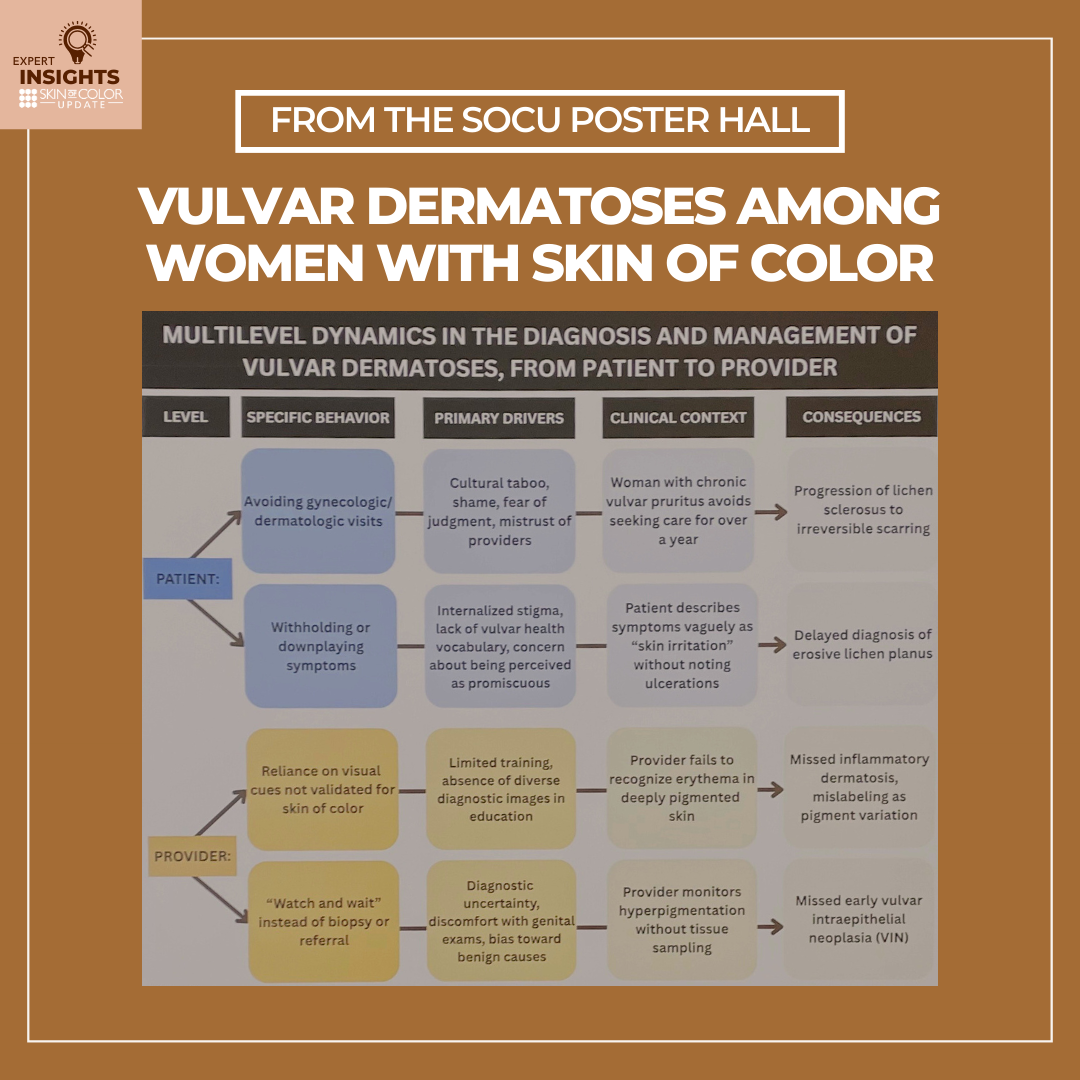

Culturally, many women grow up in environments where genital health is not discussed. Religious and social norms often portray the vulva as something shameful or linked to inappropriate sexual behavior, which creates a foundation of silence from an early age. This leads to intergenerational gaps in basic knowledge, a reluctance to describe symptoms due to embarrassment or fear of judgment, and a tendency to self-manage until the condition becomes severe, further contributing to delayed presentation. Internalized shame deepens these barriers. Many women interpret vulvar symptoms as a reflection of personal responsibility rather than a medical issue, which makes it challenging to seek help. In clinical encounters, shame often appears as vague or incomplete histories, hesitation to disclose sensitive details, or avoidance of the genital examination. Each of these behaviors limits the information clinicians need for an accurate diagnosis. There are also broader systemic obstacles. Women may struggle with limited insurance coverage, long wait times to access specialists, language barriers, or clinical settings where providers appear rushed, dismissive, or uncomfortable discussing vulvar concerns. When patient hesitation intersects with provider uncertainty, the result is a persistent cycle in which opportunities for early diagnosis are missed, and conditions are identified only after they have progressed.

You also mention that there are some barriers that a woman with skin of color may experience when seeking medical care for vulvar dermatoses. What are some of those barriers?

Women with skin of color often face barriers that arise from both societal influences and systemic inequities, and these factors significantly delay disclosure and access to care. Intergenerational silence around vulvar health limits the transmission of knowledge about anatomy, hygiene, and symptom recognition. Without this foundational understanding, it becomes harder for patients to identify early signs of disease or feel confident seeking care. Historical medical mistrust and experiences of perceived racial bias further contribute to hesitation, creating a situation where women may delay appointments, discontinue follow-up, or avoid examinations altogether. There are also provider-level challenges that directly affect diagnostic accuracy. Many clinicians receive limited training in recognizing vulvar disease on darker skin, which often leads to reliance on visual cues that were validated primarily in lighter skin. Because erythema and certain textural changes can appear differently on darker skin tones, inflammation may be underestimated and pigmentary alterations may be misinterpreted. This pattern frequently leads to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment, such as repeated antifungal therapy for presumed candidiasis while underlying inflammatory conditions remain untreated. Limited representation of skin of color in educational resources and the absence of inclusive diagnostic criteria further contribute to prolonged diagnostic delays. Together, patient-level and provider-level barriers extend the diagnostic timeline, increase the risk of irreversible scarring or malignant transformation, and encourage self-management in place of medical evaluation. Addressing barriers requires improving patient education, strengthening provider training, and ensuring that diagnostic guidelines accurately reflect the full spectrum of skin tones.

How good of a job are clinicians doing in diagnosing vulvar dermatoses in women with skin of color?

Clinicians have room for improvement when diagnosing vulvar dermatoses in women with skin of color, and the data makes this clear. Providers receive very little formal training in vulvar dermatology overall, and even less in diagnosing disease on darker skin. Inflammatory signs like erythema are harder to detect in deeply pigmented skin, yet most diagnostic guidelines and textbooks still rely on images of light skin, which leads to misclassification and delayed recognition. Importantly, women of color are almost entirely absent from vulvar treatment studies, a recent study demonstrated Black women represent as little as 1–3% of participants, so clinicians lack evidence-based expectations for how these diseases present in skin of color. Overall, the system has not prepared clinicians well. The result is underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, and delayed treatment in women of color.

Your poster calls for a “fundamental reorientation of how dermatology approaches genital health in historically marginalized populations.” What would that entail?

A fundamental reorientation means shifting from a model where genital health is treated as a narrow subspecialty to one where it is recognized as a part of equitable dermatologic care. For historically marginalized populations, this begins with strengthening education. Clinicians need training that reflects the full range of skin tones and includes clear examples of how inflammation, pigment change, and scarring appear on darker skin. Medical students and residents should receive structured instruction in vulvar examinations rather than learning informally or incidentally. Reorientation also requires more inclusive research. Women of color have been largely absent from vulvar dermatology studies, which leaves clinicians without evidence-based descriptions of how disease presents in these populations. Increasing representation in clinical trials and epidemiologic studies is imperative for improving diagnostic accuracy and treatment guidance. Culturally sensitive communication must also play a central role. Many women of color approach genital health with fear of stigma, shame, or dismissal, and clinical environments need to feel safe, respectful, and supportive. Providers should use patient-centered language, trauma-informed exam practices, and approaches that acknowledge medical mistrust and prior negative experiences. Finally, this shift involves recognizing that vulvar health does not exist in isolation from social and structural conditions. Improving outcomes requires collaboration between dermatology, gynecology, and community-based organizations to ensure that care is accessible, respectful of cultural context, and responsive to patient needs. Reorientation means expanding dermatologic care in order for genital health, skin of color, and cultural context to be integrated into routine practice rather than treated as separate or secondary concerns.

Is there anything else dermatology clinicians should know about vulvar dermatoses in women with skin of color?

Clinicians should recognize that the research base guiding vulvar dermatology remains incomplete. Women of color are underrepresented in treatment studies, case series, and clinical trials, which limits the development of evidence-based descriptions of how vulvar diseases present across diverse skin tones. This places a greater responsibility on clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating symptoms in women with skin of color and to use multiple assessment strategies including palpation, dermoscopy, and biopsy when visual cues are subtle or atypical. Clinicians should also avoid relying exclusively on textbook images that primarily feature lighter skin, since these resources do not reflect diverse patients encountered in practice. Approaching vulvar complaints with a broader and more inclusive framework allows clinicians to improve early recognition, support more accurate diagnosis, and help reduce the long-term morbidity that results from delayed or missed detection.

Additional authors of the poster include:

Daniela Rizzo, BS, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine

Anna Carter, BS, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

Kiratpreet Sraa, BS, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine

Neena Edupuganti, DO, Piedmont Medical Center

Kathleen Click, DO, Creighton University School of Medicine

Stuti Prajapati, DO, MS, St. John’s Episcopal Hospital,

Kelly Frasier, DO, MS, Northwell

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Skin of Color Dermatology here.