Delivering effective dermatologic care for patients with skin of color requires a deep understanding of their unique needs. In her presentation at the Skin of Color Update, Dr. Amy McMichael, professor in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest School of Medicine, shared practical insights on managing non-scarring alopecia, emphasizing the importance of considering both biological and cultural factors to optimize treatment outcomes. She also touched on the latest advances in therapies for alopecia areata, emphasizing the need for personalized care and thorough evaluation of hair care practices. As a leading expert in hair and scalp disorders, her contributions have significantly advanced care for diverse patient populations.

Hair Breakage and Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Dr. McMichael emphasized that hair breakage, particularly in African American patients, is often linked to acquired trichorrhexis nodosa, where the hair shaft becomes fragile and breaks easily. Her research pointed to the role of physical trauma from hairstyling and product use, rather than inherent hair structure, as a significant cause of the condition.1 This underscores the need for specific questioning of the patient on their hair care practices (combing, washing, drying, product use, chemical use, etc). She highlighted a study which demonstrated significantly higher hair breakage in African American women compared to Caucasian women.2 Dr. McMichael explained that chemical treatments, such as relaxers, and thermal styling, like flat ironing, damage the hair cuticle by stripping protective fatty acids, leading to breakage.3

Management strategies include:

-

- Check underlying abnormalities (iron levels, thyroid, nutrition, etc)

- Ceasing chemical and thermal styling for 6-12 months. During this interim, place a hair weave that is not too tight and will allow hair care.

- Utilize a layering moisturizing regimen which includes a moisturizing shampoo and conditioner, leave-in conditioners and oils, to protect and hydrate the hair.

- Regular trimming every 6-8 weeks and advising patience, as it may take months to see improvement.

Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA)

A significant portion of Dr. McMichael’s presentation covered androgenetic alopecia (AGA), a patterned form of hair loss affecting both men and women. AGA is highly influenced by genetics and androgen sensitivity, with significant variability based on sex and age.

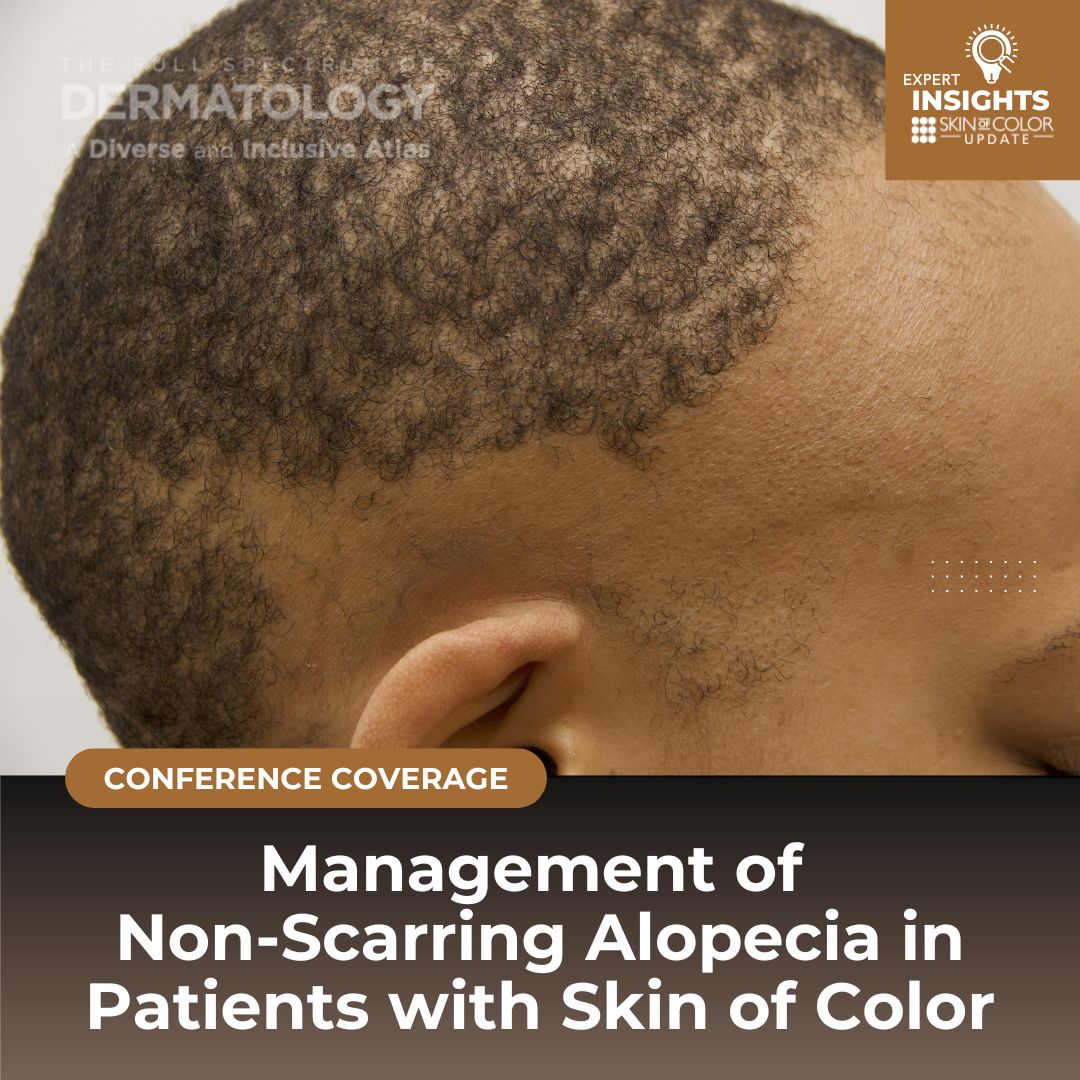

In men, hair loss typically presents as thinning at the crown and frontal scalp, while women may experience diffuse thinning across the scalp, particularly in the bitemporal regions. Diagnosis is made through scalp and hair examinations, scalp dermoscopy, trichograms, and scalp biopsies. Dr. McMicahel highlighted the importance of examining the entire scalp as it is important to distinguish AGA from telogen effluvium and traction alopecia.

Minoxidil as a Cornerstone Treatment

Dr. McMichael emphasized the critical role of minoxidil in treating AGA. Her detailed discussion on both topical and oral minoxidil provided key insights for dermatologists managing patients with AGA:

-

- Topical Minoxidil (5%): Dr. McMichael recommended the 5% solution or foam for both men and women, noting that the 2% solution is less effective for women. While topical minoxidil is a standard treatment, it can lead to side effects like scalp pruritus and hypertrichosis.

- Potential Challenges: Dr. McMichael emphasized that shedding during the first 4-6 weeks of minoxidil use is normal due to the synchronization of the hair growth cycle. Patients need to be informed about this to avoid premature discontinuation of treatment.

- Oral Minoxidil: Increasingly used as a low-dose oral option, minoxidil offers a more potent effect on hair regrowth.

- A 24-week randomized open study found that oral minoxidil (1.25-5 mg daily) increased total hair density by 12%, compared to 7.2% with the topical formulation. Despite its benefits, oral minoxidil can cause side effects such as pretibial edema, which occurred in 4% of patients, and hypertrichosis, which was more frequent in oral users (27% compared to 4% with topical use).4

- Combination Therapy: Dr. McMichael highlighted the benefits of combining low-dose oral minoxidil with spironolactone. In one 12-month observational study, a combination of minoxidil (0.25 mg) and spironolactone (25 mg) led to significant reductions in hair loss severity and shedding.5

- Dosing Guidelines for Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil: Dr. McMichael shared upcoming consensus guidelines from a group of hair experts:

- Adult females: 1.25 mg daily (range 0.625–5 mg).

- Adult males: 2.5 mg daily (range 1.25–5 mg).

- Adolescents: Females (0.625–2.5 mg), Males (1.25–5 mg).

- Common side effects include hypertrichosis and peripheral edema. Contraindications include pregnancy, pericardial effusion, heart failure, and other serious health conditions.

- Patient Education: Dr. McMichael addressed common misconceptions about minoxidil, such as the belief that stopping minoxidil use will cause irreversible hair loss. She explained that hair regrowth from minoxidil treatment requires continuous application, much like long-term use of medications for chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes.

- Topical Minoxidil (5%): Dr. McMichael recommended the 5% solution or foam for both men and women, noting that the 2% solution is less effective for women. While topical minoxidil is a standard treatment, it can lead to side effects like scalp pruritus and hypertrichosis.

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Injections for AGA

PRP is an increasingly popular treatment for AGA. PRP is derived from the patient’s own blood and injected into the scalp to stimulate hair growth and improve hair density. The treatment is suspected to work by releasing growth factors that promote angiogenesis and healing in the hair follicles.6

-

- Procedure: PRP injections are performed using 1-3 syringes with 30g needles, administering 0.2-0.5 mL aliquots into the subdermal plane. Dr. McMichael recommends an initial series of three treatments spaced 4 weeks apart, followed by maintenance treatments every 3-4 months.

- Patient Comfort: To reduce discomfort during the procedure, local lidocaine or a cryogen cooler can be used.

- Effectiveness: PRP has shown positive results in increasing hair growth and improving hair density. It is often used in conjunction with other therapies, such as minoxidil, for enhanced results.

In addition to minoxidil and PRP, Dr. McMichael discussed several other treatments available for androgenetic alopecia, including but not limited to spironolactone, finasteride, dutasteride, exosomes, laser therapy, hair transplantation, and camouflage techniques.

Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata is an autoimmune condition, with global prevalence around 2%. The condition involves non-scarring hair loss and can range from small patches to total body involvement. Dr. McMichael stressed the importance to differentiate alopecia areata from look-alikes including CCCA, tinea capitis, FFA, and cutaneous sarcoidosis. She offered a landscape of treatment modalities including corticosteroids, PUVA/NbUVB, minoxidil, anthralin, methotrexate, cosmetic options, while focusing specifically on the JAK inhibitors. Dr. McMichael shared the current approved JAK inhibitors including tofacitinib, ritlecitinib, baricitinib, and deuroxolitinib. A caveat with deuroxolitinib was mentioned that the FDA released a warning that this should not be used in patients who are CYP2C9 poor metabolizers or who are taking moderate/strong CYP2C9 inhibitors; stating that clear guidelines on how to approach this are still pending. She also highlighted that upadicitinib is currently in trials right now for this indication. She additionally highlighted the potential side effects of JAK inhibitors including but not limited to infection, thrombosis, cardiovascular events, and malignancy, as well as mentioned the necessity for laboratory monitoring.

Dr. McMichael emphasized the need for more studies on the genetics of alopecia areata, particularly in African American patients, to better tailor treatments.

Traction Alopecia

Finally, Dr. McMichael concluded her talk mentioning traction alopecia which is a common form of hair loss in African American women due to hairstyles that apply excessive tension to the hair. She again stressed the importance of utilizing dermoscopy findings to guide treatment. Regarding management, she recommended reducing friction and traction in the affected area, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, topical and oral minoxidil, and following improvement with photos with discussing the fragility of regrowth.

Conclusion

Dr. McMichael’s presentation provided a comprehensive overview of non-scarring alopecia in patients with skin of color. Her detailed discussion on minoxidil, PRP injections, and other treatment options for androgenetic alopecia offered valuable insights for dermatologists. She emphasized the need for patient education, personalized treatment plans, and ongoing research to improve outcomes for patients with diverse hair types.

References

-

- Khumalo NP, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. Apparent fragility of African hair is unrelated to the cystine-rich protein distribution: a cytochemical electron microscopic study. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14(4):311-314. doi:10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00288.x

- Lewallen R, Francis S, Fisher B, et al. Hair care practices and structural evaluation of scalp and hair shaft parameters in African American and Caucasian women. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14(3):216-223. doi:10.1111/jocd.12157

- Swee W, Klontz KC, Lambert LA. A nationwide outbreak of alopecia associated with the use of a hair-relaxing formulation. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(9):1104-1108. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.9.1104

- Ramos PM, Sinclair RD, Kasprzak M, Miot HA. Minoxidil 1 mg oral versus minoxidil 5% topical solution for the treatment of female-pattern hair loss: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):252-253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.060

- Sinclair RD. Female pattern hair loss: a pilot study investigating combination therapy with low-dose oral minoxidil and spironolactone. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(1):104-109. doi:10.1111/ijd.13838

- Alves R, Grimalt R. A Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma: History, Biology, Mechanism of Action, and Classification. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(1):18-24. doi:10.1159/000477353

This information was presented by Dr. Amy McMichael during the 2024 Skin of Color Update conference. The above session highlights were written and compiled by Dr. Nidhi Shah.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more here.