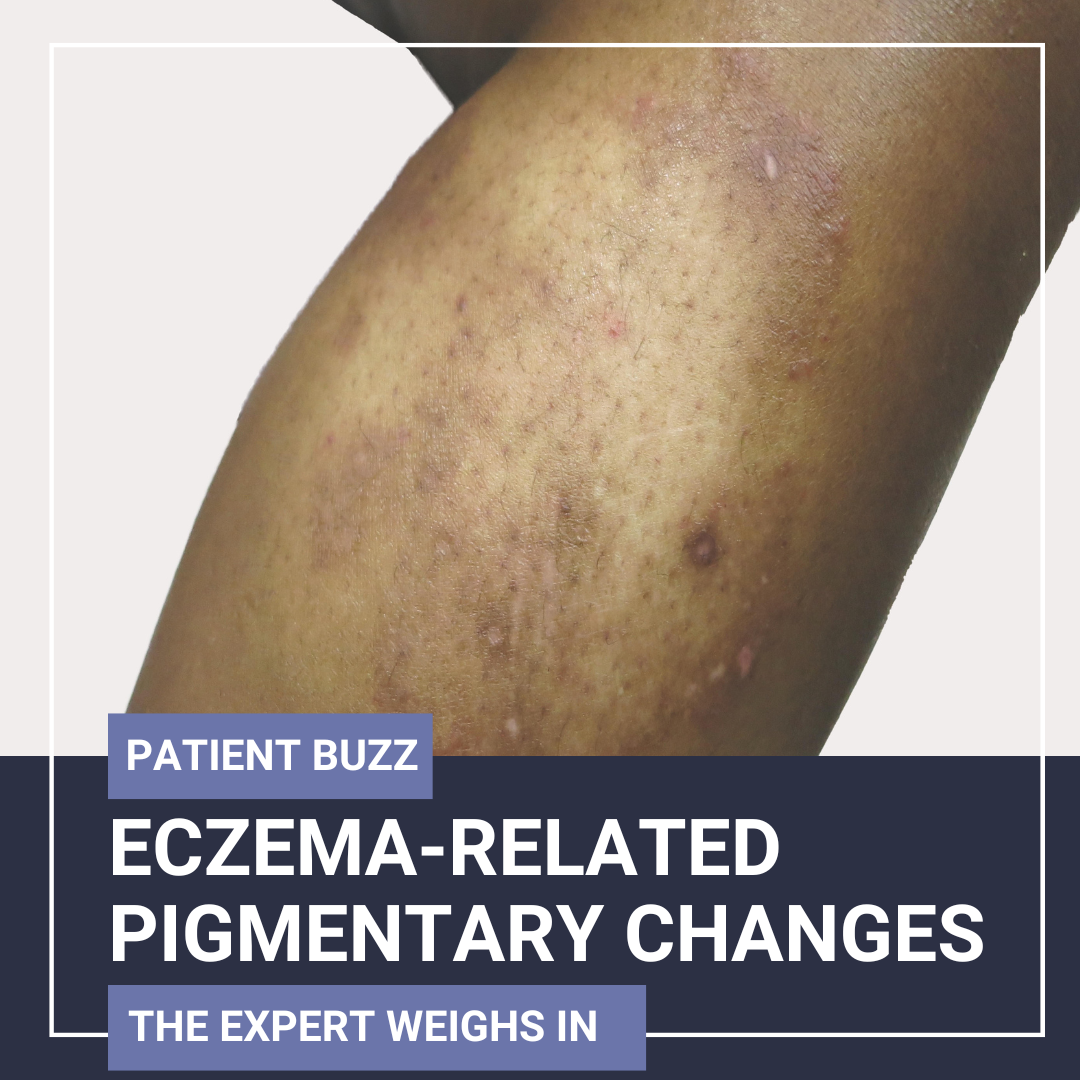

A recent Allure article addressed pigmentary changes that can occur after an eczema flare in patients with skin of color. The resulting hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can be more frustrating to patients than eczema itself.

I interviewed Rebecca Vasquez, MD, FAAD, associate professor with the UT Southwestern Medical Center Department of Dermatology. Dr. Vasquez will present on the miscellaneous causes of hyperpigmentation at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium, to be held June 7 and 8 in Chicago.

How common is it for patients with skin of color who have eczema to experience pigmentary issues post-flare? When these patients present in your office, what are their complaints?

Post-inflammatory pigmentary changes are very common in patients with skin of color who have eczema, especially those with more deeply pigmented skin (or Fitzpatrick types III–VI). In some cases, the pigment changes are more troubling to the patient than the eczema flare itself.

Common patient concerns include:

-

- “Is the eczema still active?”

- “Why hasn’t the color returned to normal?”

- “How long will it take to fade?”

- “Will this leave a permanent mark?”

Some patients worry that the discoloration means the eczema has not resolved, while others are frustrated by the lasting cosmetic impact.

What factors influence the development of pigmentary sequelae in people with conditions such as eczema? What are your tips for reducing itch as a factor?

There are several factors that influence pigmentary sequelae. Patients with more richly pigmented skin can develop more noticeable pigmentary changes. Prolonged or severe flares increase the risk of pigment alteration. Repeated excoriation can worsen pigmentation as can sun exposure. Delayed treatment means a slower control of inflammation that can lead to more post-inflammatory pigmentation.

To reduce itch and break the itch-scratch cycle, I tell my patients to use emollients liberally and regularly to maintain the skin barrier. Wet wraps (with topical steroids) may be helpful for acute flares. With regards to medications, I initiate early anti-inflammatory therapy, such as topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or other systemic agents (depending on severity of itch). I also consider oral antihistamines. Encouraging non-scratching behaviors is very important as well. I tell my patients to keep their nails short and to use distraction techniques to reduce the urge to itch.

Are there any differences in the presentation of pigmentary disorders that result from an inflammatory skin condition compared with pigmentary disorders in general?

Yes. Pigmentary sequelae from inflammation tend to follow the distribution of the prior inflammatory rash and are usually brown to dark brown macules or patches in areas of prior rash. These have ill-defined borders, especially if scratching was present, and may be hypopigmented in some patients, particularly after aggressive treatment or in the early healing phase.

In contrast, primary pigmentary disorders (e.g., lichen planus pigmentosus, erythema dyschromicum perstans) may present with bluish-gray or violaceous macules early on. These will be more symmetrical or photo-distributed and appear without a preceding rash in some cases. They also have a longer, often relapsing course.

In other primary pigmentary disorders, such as melasma or idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, lesions usually have well-demarcated patterns and a predictable distribution (e.g., melasma on the cheeks/forehead) with no history of prior inflammation or active dermatitis in the affected area.

How should dermatology clinicians treat these pigmentary sequelae?

In post-inflammatory pigment changes (e.g., from eczema or dermatitis), the first priority is controlling the underlying inflammation to prevent ongoing pigment disruption. I emphasize strict photoprotection, including the daily use of broad-spectrum sunscreen and sun avoidance. I also reassure patients that pigmentary changes typically fade gradually over several months once inflammation is well controlled.

What else should dermatology clinicians know about pigmentary sequelae from inflammatory skin conditions?

Prevention is key. Treat flares early and educate patients about risks of pigmentary changes. Validate patient concerns. Acknowledge the emotional and social impact of pigmentary sequelae, especially in visible areas.

Pigmentary changes often outlast the eczema, so reassure patients that gradual improvement over months is typical. Be cautious with procedures or aggressive topicals, especially in skin of color, which is more prone to discoloration. Finally, be sure to document and follow over time. Photographs can help monitor progress and support shared decision-making.

Did you enjoy this Patient Buzz Expert Commentary? You can find more here.