INTRODUCTION

CASE REPORT

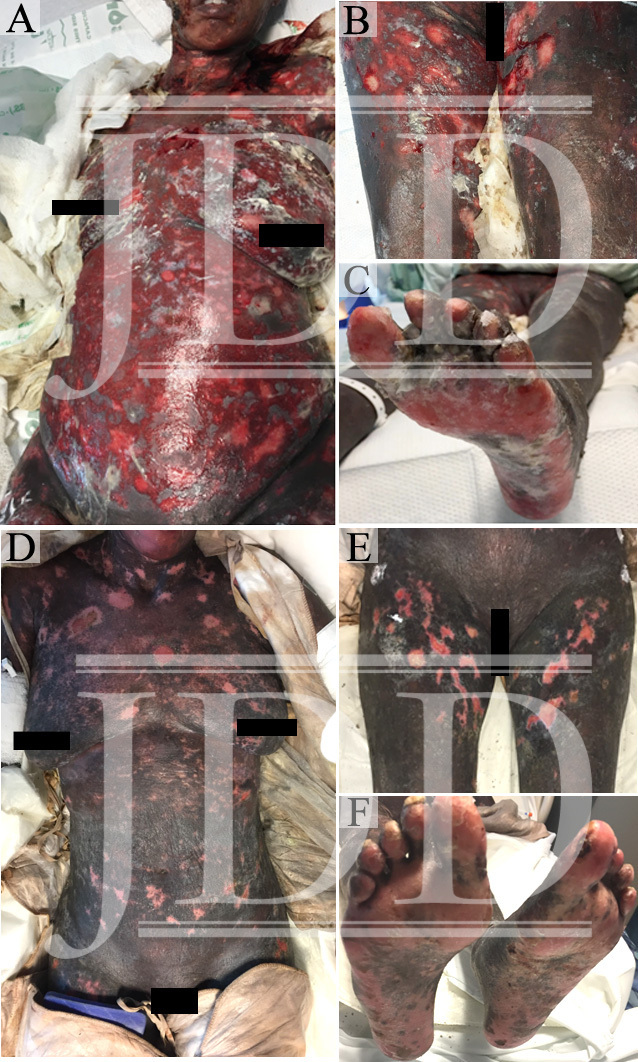

The patient’s skin continued to epithelialize and she was ultimately treated with extracorporeal photophoresis, two consecutive sessions every two weeks, acitretin 25 mg daily, and a systemic corticosteroid taper. She was discharged from hospital on day 32 and transferred to an inpatient rehab facility. The patient’s wound recovery can be seen at hospital day 19 (Figure 1D-F).

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

-

- Aapro MS, Martin C, Hatty S. Gemcitabine–a safety review. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9(3):191-201.

- Bessis D, Guillot B, Legouffe E, Guilhou JJ. Gemcitabine-associated scleroderma-like changes of the lower extremities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(2 Suppl):S73-76.

- D’Epiro S, Salvi M, Mattozzi C, et al. Gemcitabine-induced extensive skin necrosis. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:831616.

- Korniyenko A, Lozada J, Ranade A, Sandhu G. Recurrent lower extremity pseudocellulitis. Am J Ther. 2012;19(4):e141-142.

- Contreras-Steyls M, Lopez-Navarro N, Gallego E, Moyano B, Estrada D, Herrera E. Gemcitabine therapy-associated cutaneous vasculitis with a polyarteritis nodosa-like pattern. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(8):1029-1031.

- Corella F, Dalmau J, Roe E, Garcia-Navarro X, Alomar A. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with gemcitabine therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(1):97-99.

- Lai-Tiong F, Duval Y, Krabansky F. Gemcitabine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in a patient with lung cancer: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(3):1201-1203.

- Turner JL, Reardon J, Bekaii-Saab T, Cataland SR, Arango MJ. Gemcitabine-Associated Thrombotic Microangiopathy: Response to Complement Inhibition and Reinitiation of Gemcitabine. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016; S1533-0028(16):30178-5.

- Saif MW, Xyla V, Makrilia N, Bliziotis I, Syrigos K. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with gemcitabine: rare but real. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8(3):257-260.

- Humphreys BD, Sharman JP, Henderson JM, et al. Gemcitabine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Cancer. 2004;100(12):2664-2670.

- Kuhar CG, Mesti T, Zakotnik B. Digital ischemic events related to gemcitabine: Report of two cases and a systematic review. Radiol Oncol. 2010;44(4):257-261.

- Holstein A, Batge R, Egberts EH. Gemcitabine induced digital ischaemia and necrosis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19(3):408-409.

- del Pozo J, Martinez W, Yebra-Pimentel MT, Almagro M, Pena-Penabad C, Fonseca E. Linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis induced by gemcitabine. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(7-8):891-893.

- Ruiz-Casado A, Gutierrez D, Juez I. Erysipeloid rash: A rare adverse event induced by gemcitabine. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11(4):1024.

- Zustovich F, Pavei P, Cartei G. Erysipeloid skin toxicity induced by gemcitabine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(6):757-758.

- Schwartz BM, Khuntia D, Kennedy AW, Markman M. Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall dermatitis following whole pelvic radiation therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(2):421-422.

- Burstein HJ. Side effects of chemotherapy. Case 1. Radiation recall dermatitis from gemcitabine. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(3):693-694.

- Bar-Sela G, Beny A, Bergman R, Kuten A. Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall dermatitis: case report. Tumori. 2001;87(6):428-430.

- Sommers KR, Kong KM, Bui DT, Fruehauf JP, Holcombe RF. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in a patient receiving concurrent radiation and gemcitabine. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14(8):659-662.

- Mermershtain W, Cohen AD, Lazarev I, Grunwald M, Ariad S. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with gemcitabine therapy in a patient with metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Chemother. 2003;15(5):510-511.

- Calista D, Landi C. Cytarabine-induced acral erythema: a localized form of toxic epidermal necrolysis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;10(3):274-275

- Ozkan A, Apak H, Celkan T, Yuksel L, Yildiz I. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after the use of high-dose cytosine arabinoside. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18(1):38-40.

- Figueiredo MS, Yamamoto M, Kerbauy J. [Toxic epidermal necrolysis after the use of intermediate dose of cytosine arabinoside]. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 1998;44(1):53-55.

- Jidar K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Gemcitabine treatment in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a multicentre study of 23 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):660-663.

- Network NCC. Mycosis Fungoides/Sezary Syndrome (Version 1.2016). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/t-cell.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2017.

- Chung CG, Poligone B. Cutaneous T cell Lymphoma: an Update on Pathogenesis and Systemic Therapy. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10(4):468-476.

- Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: An update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(4):545-570.

Source:

Patrick M. Zito DO PharmD, Adrianna M. Gonzalez BS, Joshua D. Fox MD, Megan Cronin MD, Nicholas Mackrides MD, Robert S. Kirsner MD PhD, and Anna J. Nichols MD PhD (2018). Widespread Skin Necrosis Secondary to Gemcitabine Therapy 17(5).

https://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961618P0582X

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this case report? Find more here.