Introduction

The term “skin of color” generally refers to individuals from a broad group of racial and ethnic backgrounds including, but not limited to, Black, Asian, Latinx, American Indian, and Pacific Islander, as well as those of mixed race.1 According to the U.S. Census, the population will increase to comprise over 50% persons of color by the year 2042.2 However, the demographics of the physician workforce do not reflect these changing demographics. In one retrospective study of nearly 150,000 primary care physicians, only 13.4% self-identified as underrepresented in medicine.3 The field of dermatology lags even further behind primary care specialties in reflecting the changing U.S. population.4–6

While all physicians, and in particular dermatologists, should be confident in treating patients of color, data has demonstrated that dermatology residents have expressed a lack of formal education and confidence in treating this patient population.7–9 In order to address this identified knowledge gap, we created a week-long curriculum focusing exclusively on skin of color for dermatology residents at a Midwestern residency program. The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the effect of this curriculum on the perception of dermatology residents’ comfort level treating patients of color and to determine if this type of curriculum could be expanded to other dermatology residents.

Materials and Methods

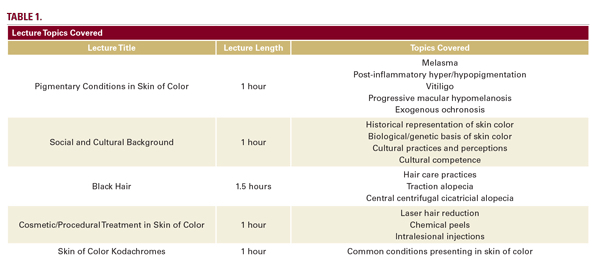

One-hour lecture sessions were implemented for dermatology residents at an urban academic medical center. Lectures contained information specific to the cultural and medical nuances of skin of color (Table 1).

The five lectures were held within a one-week time frame. Lecturers included two academic physicians with clinical and research focus on skin of color as well as one dermatology resident with an interest in skin of color. Lecture audience included thirteen dermatology residents, ranging from first-year to third-year residents. Each lecture had the same number of attendees. Topics for the lectures were chosen based on existing gaps in dermatology resident education as well as overall relevance to caring for patients of color (Table 1). Compensation was not provided to participants.

A pre-post design was implemented to collect information on learner satisfaction and knowledge gain. Pre-intervention, residents were anonymously surveyed about their exposure, knowledge, and confidence treating and understanding patients of color with various dermatologic conditions. Following the final lecture, residents completed a similar survey and gave feedback on each lecture. Data were analyzed by grouping responses on a five or ten-point scale, through yes or no answers, or free response.

Results

There were 13 total participants in this study (4 first-year residents, 4 second-year residents, and 5 third-year residents). Participants attended all lectures and completed the pre- and post-intervention surveys.

When asked about exposure to patients of color during their dermatology residency on a scale of 1 (minimal exposure, ~20% of patients) to 5 (significant exposure, 100% of patients), responses ranged from 1 to 3 with a mean of 2.09.

Overall, 100% of learners felt that their ability to care for patients of color was improved by this curriculum. All learners felt that the skin of color curriculum should be an annual component of their dermatology academic curriculum and that other dermatology residents would benefit from this curriculum.

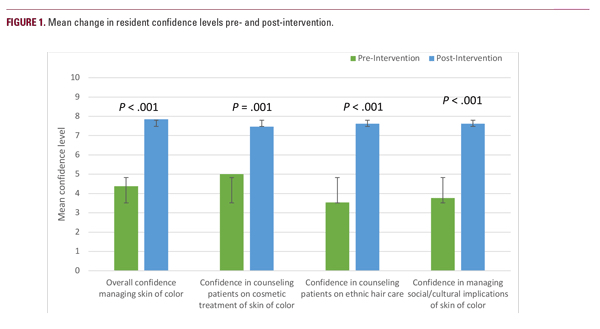

When asked to rate their overall confidence in managing patients with skin of color on a scale from 1 (minimally confident) to 10 (extremely confident), mean score went from 4.4 pre-intervention to 7.8 post-intervention (mean increase of 3.23) (P< .001) (Figure 1). Similarly significant increases in confidence level were demonstrated regarding counseling patients on cosmetic treatments, discussing ethnic hair care practices, and managing the social and cultural implications of skin of color (Figure 1).

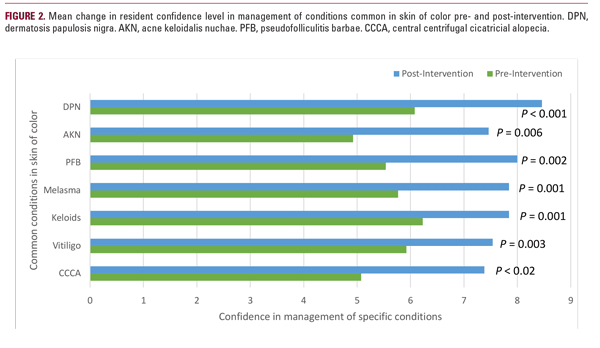

Regarding the treatment of specific conditions common in skin of color, confidence improved in the treatment of several conditions common in skin of color. The most significant changes were noted in the management of acne keloidalis nuchae (mean increase of 2.54) (P< .003) and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (mean increase of 2.31) (P< .001), with mean pre-intervention confidence scores of 5 out of 10 for both conditions (Figure 2).

When asked open-ended questions about the most useful part of the week-long curriculum, residents cited the black hair lecture as a highlight of the curriculum, which included a hands-on demonstration of black hair-care products. Additionally, residents specified that they benefited from the focused, week-long structure to the curriculum. When asked what additional topics residents would recommend for future curricula, common themes included the incorporation of more information focusing on American Indian, Asian and Latinx patients.

Discussion

Previous studies have identified a clear gap in dermatology residents’ exposure to both formal and informal education on skin of color.7–9 In one study examining dermatology residents’ exposure to skin of color education, of 59 dermatology chief residents, only half (52.4%) endorsed a lecture or didactic session on skin of color during their residency.8 In another study from Australia, a country with a diversifying population, only 18% of 56 residents surveyed indicated participating in a lecture focused on skin of color in the preceding 12 months.7

In addition to residents, patients themselves have expressed a desire for dermatologists who are knowledgeable and comfortable treating patients with skin of color. In one qualitative study examining black patients’ perceptions on their dermatologic care, subjects expressed frustration with providers who seemed uncomfortable or uninformed regarding their hair and skin conditions.10

Additionally, recent events nationwide have prompted a renewed focus on the history of systemic racism in the United States. The impact of systemic racism in the house of medicine and specifically dermatology has become more apparent and it’s resolution more urgent.11

The results of this pilot study demonstrate that residents’ overall confidence in managing individual conditions and treating patients of color was improved by the focused curriculum. Participants felt that dermatology residents at-large would benefit from a similar curriculum implemented annually.

Limitations include the small sample size with all subjects from the same residency program. We recognize that reproducibility is dependent on a multitude of institutional-related factors including availability of lecturers with expertise in skin of color as well as prioritizing didactic time for this content. Additionally, we did not use a standardized objective measure to assess residents’ knowledge gains as such a tool does not yet exist.

This pilot curriculum covered a portion of the topics that could be included in a skin of color didactic curriculum. Further steps include the creation of a comprehensive curriculum on skin of color which could be disseminated broadly to both dermatology residents and practicing providers. Importantly, didactic lectures are not a substitute for in-person clinical exposure to patients of all skin types. We encourage dermatology residency programs to continue to seek out a diverse patient population for trainees to care for and learn from. We hope that this curriculum may serve as a model for other institutions to begin improving skin of color education.

Disclosures

Acknowledgment

The authors thank analyst Jen Yeh for her contribution to data analysis.

References

2. US Census Bureau Applications Development and Services Division W. US Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/ summary/np-t5-g.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2019.

3. Xierali IM, Nivet MA. The racial and ethnic composition and distribution of primary care physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29:556-570.

4. Linos E, Wintroub B, Shinkai K. Diversity in the dermatology workforce: 2017 status update. Cutis. 2017;100:352-353.

5. Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, Wintroub BU. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: A call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 74:584-587.

6. Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, Hu S, Ortega-Loayza AG, Lim HW. Diversity in dermatology: Roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

7. Wee E, Gilmore S, Rodrigues M. Australian trainee dermatologists’ opinions on skin of colour education: Does it reflect changing demographics of the population? Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e239-e240.

8. Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

9. Cline A, Winter RP, Kourosh S, Taylor SC, Stout M, Callender V, McMichael AJ. Multiethnic training in residency: A survey of dermatology residents. Cutis. 2020;105:310-313.

10. Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, Patterson S. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019; 155:1129-1134.

11. Nolen L. How medical education is missing the bull’s-eye. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2489-2491.

Source

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more on dermatology topics for patients with skin of color here.