In 1915, a young entrepreneur named Tom Lyle Williams watched his sister, Mabel, fix her singed eyebrows with a mixture of Vaseline, ash, and coal dust, and tried to recreate a similar product using petroleum, carbon black, cottonseed oil, and safflower oil.11 When his first effort with the chemistry set failed, he teamed up with drug manufacturer Parke-Davis, eventually marketing a scented, colorless cream with petroleum and oils that promised to nourish and promote the growth of eyelashes and eyebrows—although he noted that 2 to 3 boxes were needed before any noticeable improvement—under the name Maybell Laboratories. He later renamed his company Maybelline, and a world of cosmetics opened up.

Since then, eyebrow fashions have cycled through skinny vs fat, arched vs straight. Arresting, impeccably groomed eyebrows of the fifties followed the anorexic arches of the twenties, and were followed in turn by thick and thin versions over the years.9In the film and fashion world, eyebrows had become a unique calling card. Witness Audrey Hepburn’s dark, straight brows, the thick and sultry arches of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, or Frida Khalo’s defiant uni-brow. Sophia Loren shaved her brows and drew them back in using excruciatingly detailed strokes.9 All of them were instantly recognizable.

Facial Recognition

It has always been assumed, and demonstrated, that facial recognition depends primarily on the eyes.12-14 In the sixties, Professor Desmond Morris studied eye movement recordings demonstrating that the observer’s line of sight roves from the subject’s periocular region down to their mouth, and back up to the area of the eye.15 His studies emphasized the importance of the interpersonal analysis of the emotional and social context of a face.

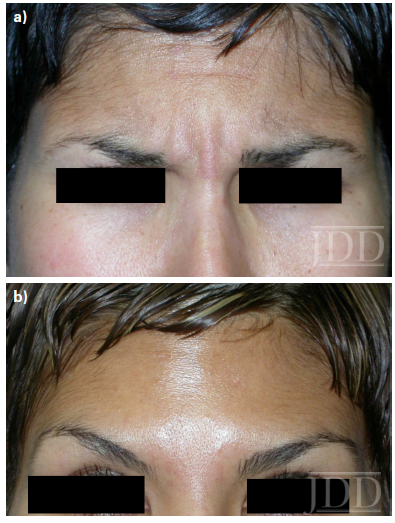

Historically, the brow ridge in the periocular region may have been an important sexually distinctive characteristic of our early ancestors’ faces: with higher levels of testosterone, men naturally have more pronounced brow ridges and eyebrows, angular jaws, and thick facial hair. Recent studies have found an important role for eyebrows in discriminating between male and female faces. Bruce and colleagues found that eyebrow thickness and position aid in gender differentiation, with thinner brows that are higher above the eye for women compared with men.16,17 Prior studies examining the key markers of facial recognition identified a hierarchy of key identifying features, with the eyes as the most important, followed by the mouth and the nose.12-14 Eyebrows were disregarded entirely or grouped together with the eyes.13 However, a more recent study demonstrates that the absence of eyebrows significantly impairs the ability to recognize familiar faces to a greater degree than the absence of eyes.18 Sadr and colleagues altered 50 photographs of celebrities using a feature omission technique in which the eyes (25 images) or eyebrows (25 images) were digitally removed while retaining the color and texture of the skin for minimal visual disruption.18 Eighteen subjects examined photographs from each set and were able to recognize 55.8% of images without eyes, but only 46.3% without eyebrows.

Communication and Emotional Response

No other feature of the face is so easily modified or so powerful as a visual form of communication. Throughout history, eyebrows have had the uncanny ability to demonstrate much without saying a word. Consider the exaggerated arches of the silent film stars like Greta Garbo that conveyed every twitch of emotion on camera. Those brows were serious; those brows were meant to speak in the absence of voice. As research has shown, eyebrows are a language unto themselves.

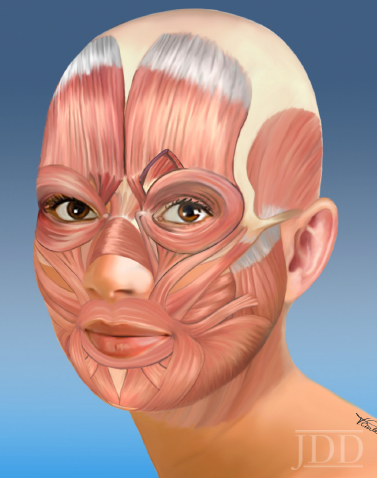

Indeed, the position of the eyebrows—elevated, depressed, or drawn together, all dependent on the interplay of elevators and depressors—is critical for emotional expression. Changes to the angle, height, and curve of the eyebrow, alone or in combination with other facial movements, can produce a broad range of signals across the spectrum of human emotion that radically alter the expression of the face and serve as nonverbal forms of communication to convey emotion.18 Maximal elevation of the medial and lateral portions of the eyebrows results in a look of surprise, depression of the medial portion depicts anger or concern, and the raising of a single eyebrow denotes a quizzical or questioning expression.8

Ekman and Friesan, pioneers in the measurement of

facial expression, compartmentalized the face into 3 regions—upper (eyebrows, forehead), middle (eyes, cheekbones), and lower (mouth, nose, and chin)—and found that the eyebrows play a key role in the expression of a number of universal emotions, including happiness, surprise, and anger.

19-23 Moreover, of the 7 visibly distinctive eyebrow actions, 5 are involved in emotional expressions, while the other 2 play a major role in a variety of conversational signals, whether on the part of the speaker or listener.

22 In American Sign Language, a signed statement automatically becomes a question with the addition of raised eyebrows.

24 The eyebrow flash is a universally recognized, yet unconscious, social signal across all primates and cultures, comprising a quick (approximately one-sixth of a second) upand- down movement in recognition and greeting, preparing the user (and receiver) for social contact.

25 Similarly, raised eyebrows during speech can signal questions, emphasize or accentuate a word or phrase, and serve as punctuation, while the brow movements of a listener may denote seriousness, importance, doubt, perplexity, or difficulty in comprehension, among other signals.

18

Conclusion

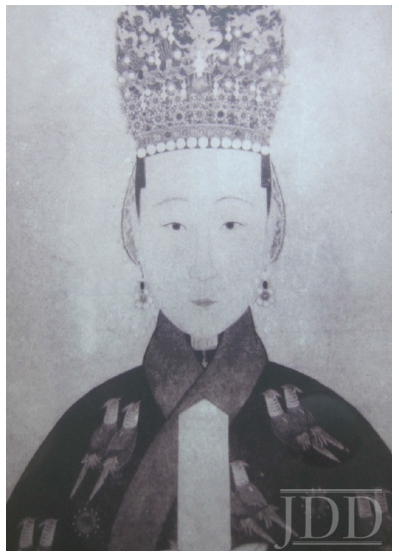

Eyebrow fashions change with the ages. In ancient Egypt, both men and women displayed natural full eyebrows. In the Middle Ages in Europe, in the age of Chivalry, the brow was seen to be important sexually, and it became fashionable for attractive women to shave or pluck their eyebrows as well as their anterior hairline to produce a pale, egg-like appearance considered appropriately demure. In the last 100 years, women have commonly altered or enhanced the shape of the eyebrows by plucking them into fine arches, a trend currently considered unnatural. Brow experts teach women how to shape their eyebrows for a fuller and more youthful look, aided by topical hair-growth products, cosmetic powders, pencils, tattoos, and even transplants.

Throughout history, the appearance of the brow has always been important, but recent research has shown that the role of the eyebrow in emotional expression defines dominance, emotion, gender, or adherence to modern fashion. It may be argued that today the brows have a greater social significance as powerful markers of facial recognition and multipurpose signalers, able to communicate a wide range of emotion and messages, to amplify verbal messages, or, even better, to communicate without saying a word.