In part 1 of this 2-part series, Dr. Kircik along with JDD authors Vlatka Agnetta MD, Abel Torres MD JD MBA, Seemal R. Desai MD, and Adelaide A. Hebert MD, reviewed the regulatory landscape of compounding in dermatology, including federal and state regulations. In part 2, they discuss FDA and USP Compounding Lists/ Categories and provide their final thoughts on in-office compounding.

FDA Compounding Lists/ Categories

Regardless of whether the medication is used topically, or by injection, the FDA has a list of bulk drug substances that may or may not be used for compounding. Under section 503A and 503B, this list allows for new nominations, additions, removal, and re-categorization of the medications on a periodic basis. In March of 2019, the FDA updated the list. Below, is the most updated list, but the reader is advised that it is subject to FDA changes and updates and should be revisited regularly for accuracy.

The FDA has put the bulk substances used in compounding into a list with three main categories based on their safety profile. Each category has a separate list for 503A and 503B compounding.

503A Bulk Criteria

Physicians and pharmacists compounding under section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) can only compound drug products from bulk drug substances meeting the following criteria:

(1) comply with the USP or National Formulary (NF) monograph if one exists, as well as the USP chapter on pharmacy compounding;

(2) if such USP or NF monograph does not exist, the bulk drug substances need to be components of FDA-approved drug products or

(3) if such USP or NF monograph doesn’t exist and the bulk substance is not an FDA-approved drug product, the drug needs to appear on the FDA’s 503A bulks list.9

503B Bulk Criteria

Currently, the outsourcing facilities operating under section 503B of the FD&C Act can only compound medication that includes a bulk drug substance if one of the two criteria are met:

(1) the bulk drug substance appears on the 503B bulks list of drug substances for which means that there is a clinical need

(2) the drug product compounded from a bulk drug substance appears on the FDA’s drug shortage list at the time of compounding, distribution, and dispensing.10

Category 1: Bulk drug substances that may be eligible for inclusion because they were nominated with sufficient in-formation for FDA to evaluate them, meaning they can be compounded.11

The 503A list of medications relevant to dermatology effective from the March 2019 update are: Aloe Vera, Capsaicin Palmitate, Coenzyme Q10, Glutathione, Glycolic Acid, Kojic Acid, Trichloroacetic Acid.12 Cantharidin and squaric acid dibutyl ester were removed from the category 1 503A list on the most recent update, and remain on the category 1 503B list.

The 503B list of medications relevant to dermatology effective from the March 2019 update are: Adapalene, Aluminum Chloride Hexahydrate, Azelaic Acid, Benzocaine, Betamethasone Acetate, Betamethasone Dipropionate, Betamethasone Sodium Phosphate, Budesonide, Bupivacaine, Calcipotriene, Cantharidin, Clindamycin Phosphate, Clobetasol Propionate, Coal Tar Solution, Dapsone, Desoximetasone, Econazole Nitrate, Epinephrine, Fluconazole, Fluocinolone Acetonide, Fluocinonide, Hyaluronic acid sodium salt, Hyaluronidase, Hydrocortisone, Hydroquinone, Imiquimod, Itraconazole, Ivermectin, Ketoconazole, Lidocaine Hydrochloride, Metronidazole, Mometasone Furoate, Monosodium Glutamate, Mupirocin, Niacinamide, Oxymetazoline HCl, Phenol, Podophyllum, Polymyxin B Sulfate, Prilocaine, Proparacaine HCl, Salicylic Acid, Sodium Bicarbonate, Sodium Chloride, Sulfacetamide Sodium Monohydrate, Tacrolimus, Tazarotene, Terbinafine HCl, Tetracaine Hydrochloride, Tretinoin, Triamcinolone Acetonide, Triamcinolone diacetate, Urea, Vitamin D, Zinc Oxide.13

Category 2: Bulk drug substances that raise significant safety concerns, meaning they cannot be compounded.11 Currently neither the 503A or 503B list of medications include any medications relevant to dermatology.

Category 3: Bulk drug substances nominated for bulk compounding without adequate support/evidence for their safety, meaning that they are restricted as not safe to compound at this time until additional safety information is gathered.11

The 503A list of medications relevant to dermatology effective from the March 2019 update are: Hyaluronic Acid Sodium Salt, Papaya enzymes, White ointment.12

The 503B list of medications relevant to dermatology effective from the March 2019 update are: Aluminum chloride, Cidofovir, Coenzyme Q10, Collagenase, Desonide, Hyaluronidase, Kojic Acid, Miconazole nitrate, Nicotinamide, Nystatin, Resorcinol, Resveratrol, Retinoic Acid-All Trans, White ointment, White petrolatum.13

USP Compounding Lists/Categories

In June 2019, the USP published an update on General chapter 795, which applies to pharmaceutical compounding of non-sterile preparations and chapter 797, which applies to pharmaceutical compounding of sterile preparations. This update takes category 1 of the FDA bulk medications and recategorizes them into two different compounding sterile preparations (CSPs) based on the compounding conditions rather than the chemical compound properties themselves.14

Category 1: CSPs may be prepared in a segregated compounding area and therefore have a shorter beyond-use date (BUD). Category 1 CSPs can be used for up to 12 hours after the compounding if at controlled room temperature, and up to 24 hours after compounding if kept refrigerated.14

A good example relevant to dermatology that fits this category is the drawing up of lidocaine from a multi-purpose vial into smaller syringes and buffering it with sodium bicarbonate for local anesthesia. Thus far, there has been great variability between different states in formulating rules on how long the in-office lidocaine compounding can be used for. These rules have been based on some highly criticized studies that showed contamination was observed after a short period of time with in–office compounding. But the latter study ignored other substantive studies, such as that by Pete et al in 2016, that demonstrated safe medication use without micro-organisms or loss of medication properties even at four weeks after in-office compounding.15 Thus far, the state rules on how long an in-office compounded injection can be used has varied greatly. One bright side to the anticipated recent USP updated guidelines is the hope that these most current USP guidelines will bring more guidance and uniformity to state rules.

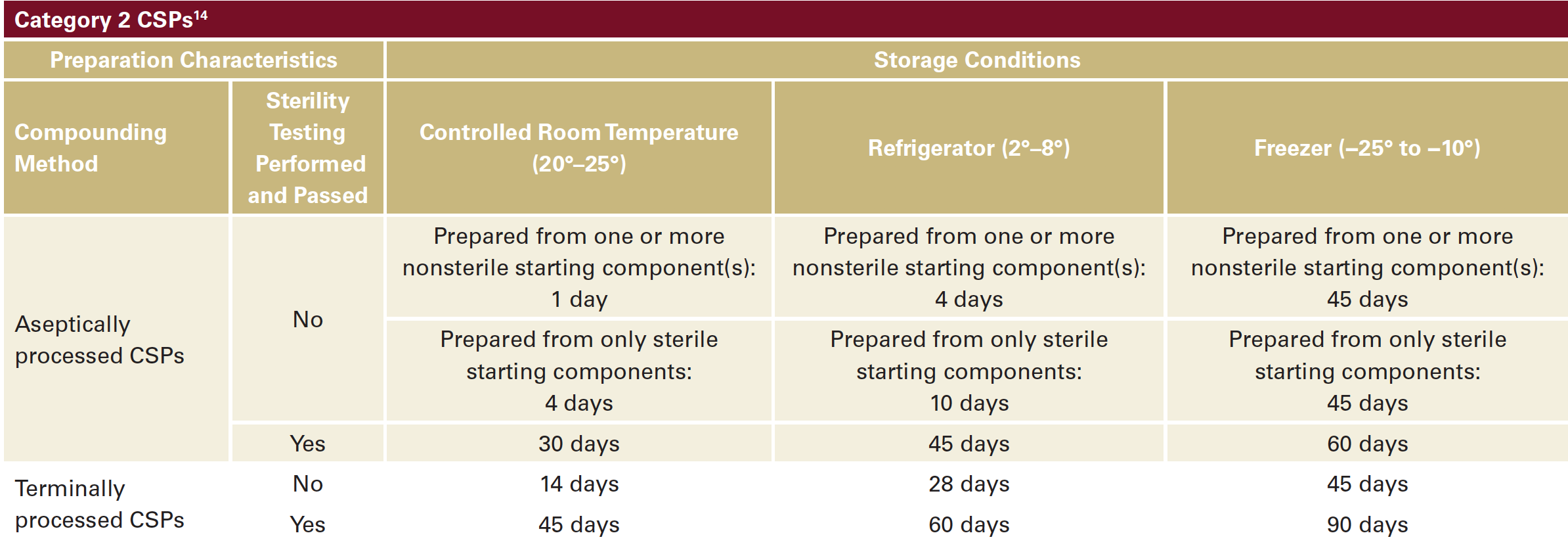

Category 2 : CSPs must be prepared in a cleanroom environment and have a longer Beyond Use Date (BUD). Category 2 have more complicated and variable rules depending on whether the compounding was processed via aseptic vs sterile methods and depending upon the temperatures at which the compounding medication is stored afterwards. The BUD can vary from 24 hours to 90 days. Below is a table that summarizes the BUDs based on the CSP2 category (Table 1).3,11 This category is not relevant to in-office compounding for dermatologists.14

In addition, a new USP General chapter 800 rule is expected to be implemented as of December of 2019. This rule refers to the safety guidelines in handling, compounding and administering hazardous medications listed on the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) website.16 This list includes medications such as methotrexate and fluorouracil used in dermatology offices for intralesional injections. Current USP guidelines mandate using negative pressure rooms, chemotherapy gloves, and other special chemotherapy protective equipment for any type of handling and administration of these medications.17 Although it may be too early at this time to know which state medical boards will implement this rule, many pharmacy state boards are planning to comply with it. This means that that any medical office or facility with a pharmacy license will be required to comply with its pharmacy state boards.

Topical Medications

Topical medications that are commonly used in dermatology pose a conundrum with a much lower safety risk for the patient than injectable medications. Nevertheless, they are still subject to the same compounding rules and regulations as injectables. Common examples of “office-use” compounded topical medications used by dermatologists include different preparations of pre-formulated numbing creams containing lidocaine, benzocaine and/or tetracaine, as well as com-pounded wart treatment formulations (eg, cantharidin), and aluminum chloride. 503A traditional pharmacies can make these formulations readily available in small amounts. However, there are several obstacles with 503A pharmacy topical compounding for dermatologists such as they require a patient-specific prescription. Yet, it may be unsafe to have a patient be in possession of medications that are intended for “in-office” physician supervised use. Since these are prescrip-tion-specific, it is also impractical and unsafe for an office to store these “in-office” use medications for each individual patient. In addition, topical compounding is also subject to the 503A bulk substances limitations and traditional pharma-cies can’t compound all topical prescriptions. Alternatively, physicians can acquire these compounded medications through 503B compounding facilities since they don’t require a patient-specific prescription. The trouble is that these medications are often available only in large quantities that are very costly and wasteful if they cannot be used by their expiration date. In addition, there area also concerns about lack of GMP controls, lack of stability, and unpredicatable shelf life, and possible variability of concentration in different batches unlike an FDA approved product. Also, these facilities are far fewer and often less accessible, which can cause a significant delay in getting these medications in a timely manner. Thus, this has led to a cacophony of complaints of the impracticality and restriction for patient care of these new regulations.

Cantharidin is an example of the compounding conundrum. It was available briefly as a 503A category 1 medication for compounding and yet in March 2019 it was moved to the 503B category 1 list. The end result is that now access for patients to this drug is significantly restricted because 503B facilities will most likely sell it in bulk orders only. This is impractical since the average dermatologist doesn’t need bulk supplies that will be costly and likely expire before they can be used in a cost-effective manner. This has resulted in physicians having to wait for a commercially available FDA approved formulation.

Conclusion

Medication compounding is an important part of medical treatments and has been used widely in many fields of medi-cine, especially dermatology. Patient safety is and should always be a primary concern in medication compounding. The rules and regulations mandated by the FDA, USP, and the individual states are constantly evolving and becoming more stringent.

While we must applaud the pursuit of safety, it needs to be recognized that this poses a challenge to in-office compound-ing and often deters the practitioners from continuing this practice due to fear of harsh penalties. As a result of this, many outpatient offices have decreased or eliminated in-office compounding. In addition, the 503B outsourcing facilities are not as readily accessible either physically or from a cost-effectiveness point of view as the 503A transitional pharmacies that are now even more limited in compounding. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and other physician organiza-tions have been actively working with the FDA, USP, and other policy-making government and non-government organizations to educate about the low risk office compounding and find the best solution to the compounding issues. In dermatology, intra-dermal anesthetics and steroid injections are widely used in everyday dermatology practice and often require dilution or mixing with a substance such as a buffer for an anesthetic in order to decrease pain with an injection. While injectable preparations are considered higher risk for adverse events and contamination than topical preparation, intra-dermal injections should be considered low risk when compared to intravenous, intra-articular, or intra-ocular injections since the side-effect profile is very different. Proper education on these low risk treatments such as topical treatments, intralesional steroid dilution, or lidocaine buffering is a key to understanding the risk benefit profile for our patients and demonstrates how these can be done safely and decrease the cost drastically. Certainly the current state of affairs is not in the best interest of our patients.

Amidst this regulatory chaos, the very first FDA-approved treatment for molluscum will be a welcome addition to our treatment armamentarium.

References

9. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/bulk-drug-substances-used-compounding-under-section-503a-fdc-act

10. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/bulk-drug-substances-used-compounding-under-section-503b-fdc-act

11. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/bulk-drug-substances-used-compounding-under-section-503a-fdc-act

12. Evaluation of Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (internet) March 2019 https://www.fda.gov/media/94155/download

13. Evaluation of Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (internet) March 2019 https://www.fda.gov/media/121315/download

14. USP General chapter 797 Pharmaceutical compounding – sterile preparations: USP_GC_797_2SUSP42.pdf

15. Shimizu P, et al. Safety of prefilled buffered lidocaine syringes with and without epinephrine. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(3):361–5.

16. NIOSH List of Antineoplastic and Other Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare Settings, 2016 https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2016-161/pdfs/2016-161.pdf

17. UPS general chapter 800, Hazardous Drugs – Handling in Healthcare setting: https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/our-work/healthcare-quality-safety/general-chapter-800.pdf

Vlatka Agnetta MD, Abel Torres MD JD MBA, Seemal R. Desai MD, Adelaide A. Hebert MD, Leon H. Kircik MD (2020). Compounding in Dermatology Update. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, 19 (2). https://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961620S0015X/1

Content used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Medical Dermatology here.

Next Steps in Derm is brought to you by SanovaWorks.