In this blog of ODAC Pearls, we’ll be discussing Dr. Adam Friedman’s ODAC lecture, “Practical Updates on Rosacea Pathophysiology and Management.” We will review the pathophysiology, comorbidities, microbiome, updates on classification and treatment of rosacea, along with practical pearls in management.

The 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee reported various rosacea comorbidities along with the strength of their associations. Some of the stronger associations included Crohn’s disease, depression, migraine, anxiety, Parkinson’s disease, celiac disease, Alzheimer’s disease, glioma, IBD, and dementia.1

So what happens in rosacea? Basically, you have a trigger (ex. inflammation, neurological and vascular dysfunction) which then leads to innate, adaptive, and neurogenic immune responses (IFN, immunoglobulins, interleukins, neuropeptides, etc.) causing release of mediators and subsequent processes of inflammation (angiogenesis, pustules, papules, pain, etc.). Once there is a trigger, multiple pathways are activated. The TLR2/cathelicidin pathway may occur in keratinocytes or mast cells. Cathelicidin can stimulate angiogenesis and induce macrophage chemotaxis. Also, inflammasome activation may occur in keratinocytes or macrophages, leading to the secretion IL-8, COX-2, and TNF. IL-8 is a chemokine for neutrophils, which are exclusive to the pustules of rosacea. COX-2 is an enzyme that activates prostaglandin E2, which causes the sensation of pain. TNF has many pro-inflammatory properties, many of which are redundant to IL-1β. These pathways can also induce production of MMPs, NO, and ROS, mediators thought to be largely responsible for the clinical signs of rosacea. TRP ion channels are expressed on neural and non-neural tissue and result in production of neuropeptides such as PACAP, substance P, CGRP, and VIP. Neuropeptides and IL-1β can also activate the adaptive immune response. Th1 and Th17 cells, associated cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-17, and plasma cells have all been found to be increased in rosacea and likely act to perpetuate the innate immune response.2,3

What is important to highlight is that rosacea shares a common general pathophysiology with many of its reported comorbidities. So the question is, should we be screening for and educating patients about these potential comorbidities? At this time, it is not currently known whether rosacea is a risk factor for the development of comorbidities or vice versa.

Cutaneous microbiota has become an increasingly popular topic, particularly in regards to its relationship with certain primary diseases like atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, acne vulgaris, and rosacea. One significant correlation with rosacea is the amount of demodex folliculorum infestation. Demodex is a part of the commensal flora. Several studies have reported on its role in rosacea, particularly the papulopustular and erythematotelangiectatic variants. Bacillus oleronius is a demodex-associated microbiota to which rosacea patients have demonstrated antibodies against.4,5 Staphyloccus epidermidis, chlamydophila pneumonia, and helicobacter pylori have also been implicated in rosacea.6,7,8

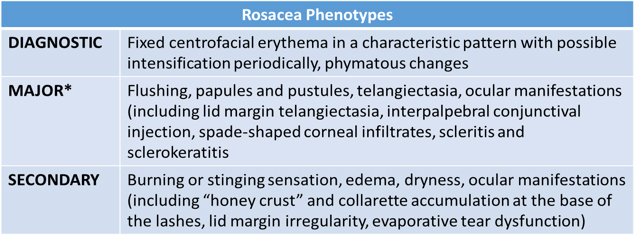

Rosacea is currently classified into 4 subtypes; however, this can be confusing, because multiple features can be present simultaneously. The Global ROSacea Consensus (ROSCO) Panel, comprised of an international panel of 17 dermatologists and 3 ophthalmologists, had consensus in establishing a phenotype-led rosacea diagnosis and classification scheme. So this is why the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee, which reviewed the standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea, was so timely. They argued that “the focus on subtypes tended to limit consideration of the full range of potential signs and symptoms that may occur in individual patients and that, in some cases, may confound the assessment of severity.”9

What is the most important management strategy for these patients? You guessed it… education on proper general skin care! As dermatologists in training, we see a lot of patients in short time intervals during our clinic time. So when your clinic is running 45 minutes behind, the last thing you want to spend time on is probably education on the etiology of a condition, preventive measures and all of the various treatment options. However, I have learned that spending just five minutes of your time to explain proper management techniques can prevent you from spending even more time in the future when that same patient returns feeling dissatisfied from the lack of improvement. Simply giving a patient a handout without explanation is not enough. So, here is a word of advice from a novice: Take the time now to save the time later!

Essential elements of skin care advice for rosacea include SPF 30+, gentle cleansers and moisturizers, and trigger avoidance.

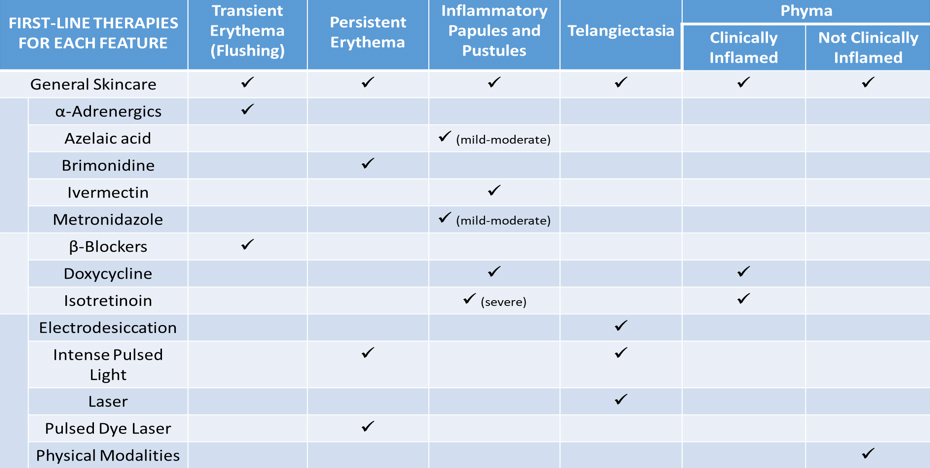

The ROSCO Panel has also issued treatment recommendations based on major phenotypic features: transient erythema, persistent erythema, inflammatory papules/pustules, and phyma. The panel considered each feature and its severity individually and based decisions on available evidence and clinical experience. Treatment for papulopustular type should vary based on severity, while treatment for phyma should depend on whether it is clinically inflamed or not. Moderate and severe presentations require a combination of treatment: general skin care, physical modalities, and pharmaceutical agents. TREATMENT PEARL!!! If the treatment fails, try again but add on!

Oxymetazoline was FDA-approved for rosacea in January 2017 for the topical treatment of persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea. The approval date was after the ROSCO panel published their treatment recommendations, but Bromidine gel (highly selective α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist), was a listed recommendation for persistent non-transient erythema of rosacea.

TREATMENT PEARL!!! A recent study published in JID reported a significant reduction in inflammatory lesions at 4 months in patients taking isotretinoin 0.25mg/kg/d as compared to placebo group. Of those patients, 58% relapsed 4 months after treatment cessation. So this should be a consideration for patients who are refractory to other therapies.10

TREATMENT PEARL!!! In patients with a higher concentration of Demodex folliculorum (which can present in various clinical forms including pustular folliculitis, papulopustular scalp eruptions, perioral dermatitis, and blepharitis), consider Permethrin or Ivermectin (topical/oral).11

How well do you know the symptoms of ocular rosacea? It’s important that we are able to recognize these features (such as foreign body sensation, blurred vision, redness, tearing, photophobia, blepharitis, etc). The current treatment recommendations are the use of UV-coated sunglasses, artificial tear substitutes for mild burning and stinging, and lid hygiene (warm compresses, lubricating drops, diluted baby shampoo scrubs, meibomian gland expression). Doxycycline 40mg MR can also be added for moderate to severe disease.

In conclusion, just remember:

1) Rosacea is a common cutaneous disorder that can be associated with other problems.

2) The role of dysbiosis is still emerging when it pertains to rosacea.

3) Combination therapies are usually best (split into a morning and evening routine).

And that’s it for now. I hope you learned some practical pearls that will be helpful when you evaluate your next rosacea patient. Before I go, I’d like to thank Azam Qureshi, our GW Dept of Dermatology medical student research fellow, for his assistance in editing and formulating the tables for this blog.

References

- Gallo R, Granstein R, Kang S, Mannis M, Steinhoff M, Tan J, and Thiboutot D. Rosacea comorbidities and future research: The 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78(1):167-170.

- M. Buhl T, Nowak P, Buddenkotte J, McDonald I, Aubert J, Carlavan I, Deret S, Reiniche P, Rivier M, Voegel JJ, Steinhoff M, Molecular and Morphological Characterization of Inflammatory Infiltrate in Rosacea reveals Activation of Th1/Th17 Pathways. The Journal of investigative dermatology, (2015).

- D. Schwab, M. Sulk, S. Seeliger, P. Nowak, J. Aubert, C. Mess, M. Rivier, I. Carlavan, P. Rossio, D. Metze, J. Buddenkotte, F. Cevikbas, J. J. Voegel, M. Steinhoff, Neurovascular and neuroimmune aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. The journal of investigative dermatology symposium proceedings 15, 53-62 (2011).

- Lacey N, Delaney K, Kavanagh K, Powell F. Mite-related bacterial antigens stimulate inflammatory cells in rosacea. Br J Dermatol 157: 474-481, 2007

- O’Reilly N, Menezes N. and Kavanagh K. Positive correlation between serum immunoreactivity to Demodex-associated Bacillus proteins and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;167(5):1032-6

- Whitfield M, Gunasingam N, Leow LJ, Shirato K, and Preda V. Staphylococcus epidermidis: A possible role in the pustules of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:49-52.

- Blasi F, Tarsia P, and Aliberti S. Chlamydophila pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:29-35.

- Mini R1, Figura N, D’Ambrosio C, Braconi D, Bernardini G, Di Simplicio F, Lenzi C, Nuti R, Trabalzini L, Martelli P, Bovalini L, Scaloni A, Santucci A. Helicobacter pylori immunoproteomes in case reports of rosacea and chronic urticaria. Proteomics 2005;5:777-87.

- Gallo R, Granstein R, Kang S, Mannis M, Steinhoff M, Tan J, and Thiboutot D. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: The 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78(1):148-155.

- Sbidian E, Vicaut E, Chidiack H, Anselin E, Cribier B, Dreno B, and Chosidow O. A randomized-controlled trial of oral low-dose isotretinoin for difficult-to-treat papulopustular rosacea. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2016; 136: 1124-1129

- Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O and Esrefoglu The clinical importance of demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. The Journal of Dermatology, 2004; 31: 618–626