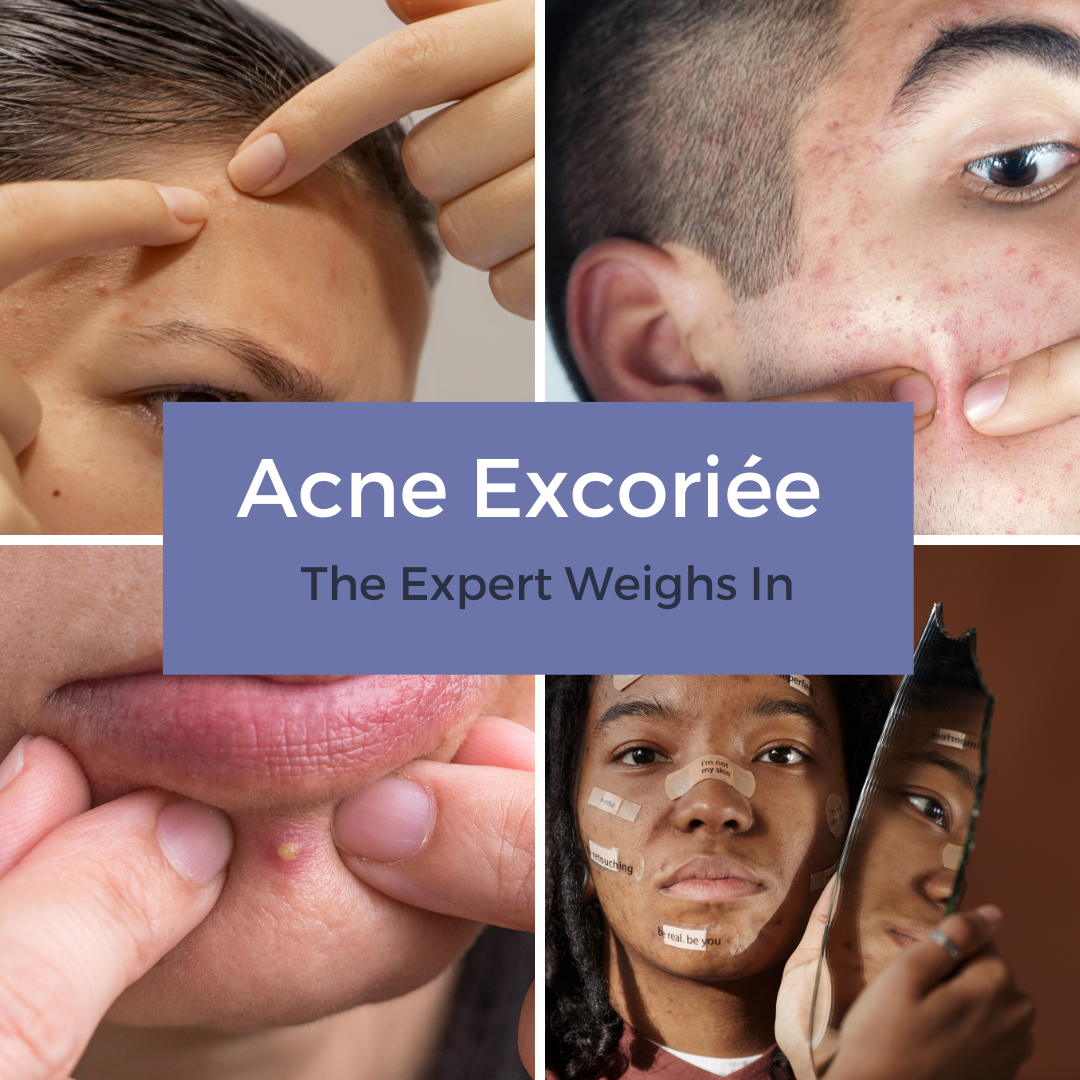

Allure recently posted a first-person account of acne excoriée. How can dermatologists best counsel patients who pick their acne lesions, and what tools can help address the urge to pick?

For expert advice, I reached out to dermatologist and clinical psychologist Rick Fried, MD, PhD, clinical director of Yardley Dermatology Associates and Yardley Clinical Research Associates in Yardley, Pa.

How common is acne excoriée among acne patients?

It’s important for dermatologists to know that every single human being messes with their skin, hair and nails. It’s not a matter of if, but how often and where. When it comes to skin disorders that other people see or potentially judge us or define us by, we are driven to make these things go away.

The actual incidence of acne excoriée is hard to pin down because the people who come in with run-of-the-mill acne often manipulate their skin yet these are not necessarily the patients who leave with a formal diagnosis of acne excoriée. While the incidence is hard to quantify, every single front-line clinician will say it’s ubiquitous in acne patients.

We are seeing more patients presenting with skin manipulation, and it’s my personal belief that this has to do with the ever-present comparatives we have at our disposal, particularly social media. With images of perfected skin – real and photoshopped – we feel increasingly imperfect in our skin.

What factors should lead to an acne excoriée diagnosis?

Factors to consider are when it’s obviously causing meaningful damage to the skin and emotional distress for the patient, as well as interfering with the patient’s ability to do things they need and want to do in their lives. Many patients with acne excoriée spend hours in front of the mirror examining and picking at their skin.

Are there any commonalities you find among patients with acne excoriée, such as age or acne severity?

I don’t find a greater preponderance in adults or teens. The incidence appears to be rising in both populations. I don’t think that acne severity necessarily correlates with greater picking behavior. If you’re a picker, you pick, often from an early age. If you are an acne sufferer, you are going to pick at your acne, and in addition, “pickers often make pickers.” It’s surprising how common it is that the patient’s parents also pick at their skin, so in some patients there may be a genetic component.

What happens to the skin when acne lesions are picked? How damaging is skin picking?

Acne excoriée is a big deal because in the short term it can lead to visible marks in terms of scabs, open sores or ulcerations. In the long term it can leave permanent and disfiguring scars. In the extreme, acne excoriée can lead to life threatening infections and nerve damage. This is a spectrum and everyone who picks at their acne falls somewhere on that spectrum.

When you make a diagnosis of acne excoriée, how do you counsel the patient?

One of the most useless things is to look at the patient and say they are a picker. Once you call someone a picker, you have given them a label but you know nothing about why they pick.

When you see an acne sufferer who has evidence of skin picking, I think a very helpful approach is to say “I want you to know that I take acne very seriously. I think it’s a big deal, and I’m extremely motivated to get your skin as clear or as clear as possible as quickly as possible.” I’ll say, “It see to me that there are areas where it looks like you have been picking. Tell me something: Do you go at the pimple or pick at the pimple because you don’t like the way it looks or feels – itches, tingles, hurts or burns?”

The next thing I think that is important to know is whether there is a goal. Is there an endpoint you have to achieve before the patient can stop going at that spot? Get the pus, fluid or blood out? Get it smooth to the skin? Because knowing why they pick can help us to tailor the best treatment for them. If they pick just because they can’t stand pus in the pimple, we may or may not give them permission to squeeze a whitehead if they know they don’t have to squeeze it until half their cheek is gone. The most useless thing we can tell them is don’t pick. I look at every single patient and say, “My job is not to tell you not to pick but to give you nothing to pick at.” That shared responsibility is important. Most people who are pickers don’t do it because they want to do it but because they have to.

It’s also important for dermatologists to normalize it. Everyone messes with their skin. I tell them, “I guess there’s someone who doesn’t pick at their skin, but I haven’t met them yet.” People frequently feel as though they are abnormal or neurotic. Legitimizing doesn’t mean they will do more of it.

How does skin picking impact your choice of acne treatments?

I do think acne excoriée is a clinical point – a box we check that says they require more aggressive acne treatment because time matters. No matter the skin condition, there’s the same question: How much, how long and how severe until there is irreparable damage to the skin and psyche?

It is very important to treat the acne in an efficacious and time-effective fashion. When we see that there is scarring or the patient is extremely distressed, I’m not going to put them on an over the counter topical agent. As long as there is a single inflammatory lesion, I’m going to treat until clear with prescription treatments.

It’s important to treat aggressively because when patients have better control over how their skin behaves, feelings of anxiety and helplessness decrease. From the moment acne treatment begins, I assure patients that most new pimples they get won’t be as big or angry and will disappear sooner. Holding out a short term carrot for them can be helpful in keeping them onboard and optimistic about their treatment.

What about patients who pick their skin even when their acne clears?

Some patients pick because there is something there while others pick because that’s what they do. People may start picking for a variety of reasons and then it becomes their default mode. Ask the patient, “Now that I understand why you pick, do you find yourself pick mindlessly?” Mindless automaticity is harder to stop.

What tools do you give patients that can can help reduce the urge to pick?

Most people have places where they pick, such as the bathroom, and once they get started, it can be hard to stop. I encourage my patients to set an alarm for two or three minutes. Give a limited time to be in the situation. Alternative behaviors can work such as pressing with a finger pad on the pimple to make it flatter or using a warm or cold compress. Defocusing, such as squeezing the index finger and thumb as hard as possible, can help, too.

Medications can also be helpful, especially with mindless picking and picking that continues once the acne clears. N-acetylcysteine is the most studied natural therapy for hair pulling and skin picking. It’s not a home run for a lot of people, but for some people it is.

Conceptually, there is some overlap with skin picking and obsessive compulsive disorder or repetitive body focus behaviors. SSRIs and SNRIs have anti-inflammatory effects in the skin and can help the nerve endings normalize, thereby decreasing automatic behaviors. Data also exists for anti-epileptic drugs such as pregabalin. Even pimozide, commonly used for Tourette syndrome, often shuts down skin picking even at very low doses. If you prescribe oral, psychiatric mediations, titrate them to the effective dose.

The Association for Psychoneurocutaneous Medicine of North America recommends tapering medicine once symptoms are well controlled for three months. If the acne is gone and they stop picking, they may never need it again. However, if the acne is gone and they resume picking, then that becomes not just an acne issue. Put those patients back on the medication for three months and then titrate.

What other advice do you have for dermatologists in diagnosing and treating patients with acne excoriée?

In our differential diagnosis, let’s make sure it is acne and not a co-infection – staph, strep or viral. Let’s make sure there is not an underlying autoimmune process or a malignant process. As soon as we label someone as anything psychiatric, we often stop thinking like a physician.

It’s also important for adherence to make an emotional connection with your patient. It’s incumbent to ask some blunt questions in order to gauge the patient’s level of anguish: How difficult is living with this and how much is it impacting your happiness and ability to function? Do you have any thoughts of hurting yourself or someone else? Many physicians don’t want to open that Pandora’s box, but asking these questions while maintaining eye contact for three seconds will create a bond whereby your patients will work harder and trust you more.

Did you enjoy this Patient Buzz expert commentary? You can find more here.