Pyoderma Gangrenosum Occurring in the Setting of Hypercortisolism Associated With Adrenocortical Adenoma: A Pathophysiological Paradox

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a challenging, rare, ulcerating skin disease characterized by neutrophilic abundance and absence of infection, often associated with systemic diseases. JDD authors Chapman Wei, Elizabeth Hazuka, Peter DeRosa, Jill M. Paulson MD, and Adam J. Friedman MD present a 25-year old previously healthy female with a 1.5-year history of treatment refractory PG. Features of Cushing’s syndrome such as facial plethora, striae, and lipodystrophy were noted on exam, which prompted several studies that ultimately revealed an adrenal adenoma. Following surgical excision of the adenoma, symptoms rapidly resolved and systemic immunosuppressants were discontinued. This rare case highlights the importance that adrenal adenoma and resultant Cushing’s syndrome may be a driver of PG despite the pathophysiologic paradox.

Case Report

A 25-year-old previously healthy female presented to dermatology with a 1.5-year history of steroid-unresponsive PG diagnosed by a previous dermatologist on her lower extremities. Previous treatment included multiple oral prednisone tapers, perilesional Kenalog injections, and topical clobetasol cream with limited to no improvement. On review of systems, the patient reported increased fatigue, easy bruisability, striae, facial redness, hip pain, and hair loss over the past six years; past laboratory testing was unremarkable. The patient denied any past medical history, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), arthritis, hematologic abnormalities, and HIV. She reported no relevant family or social history.

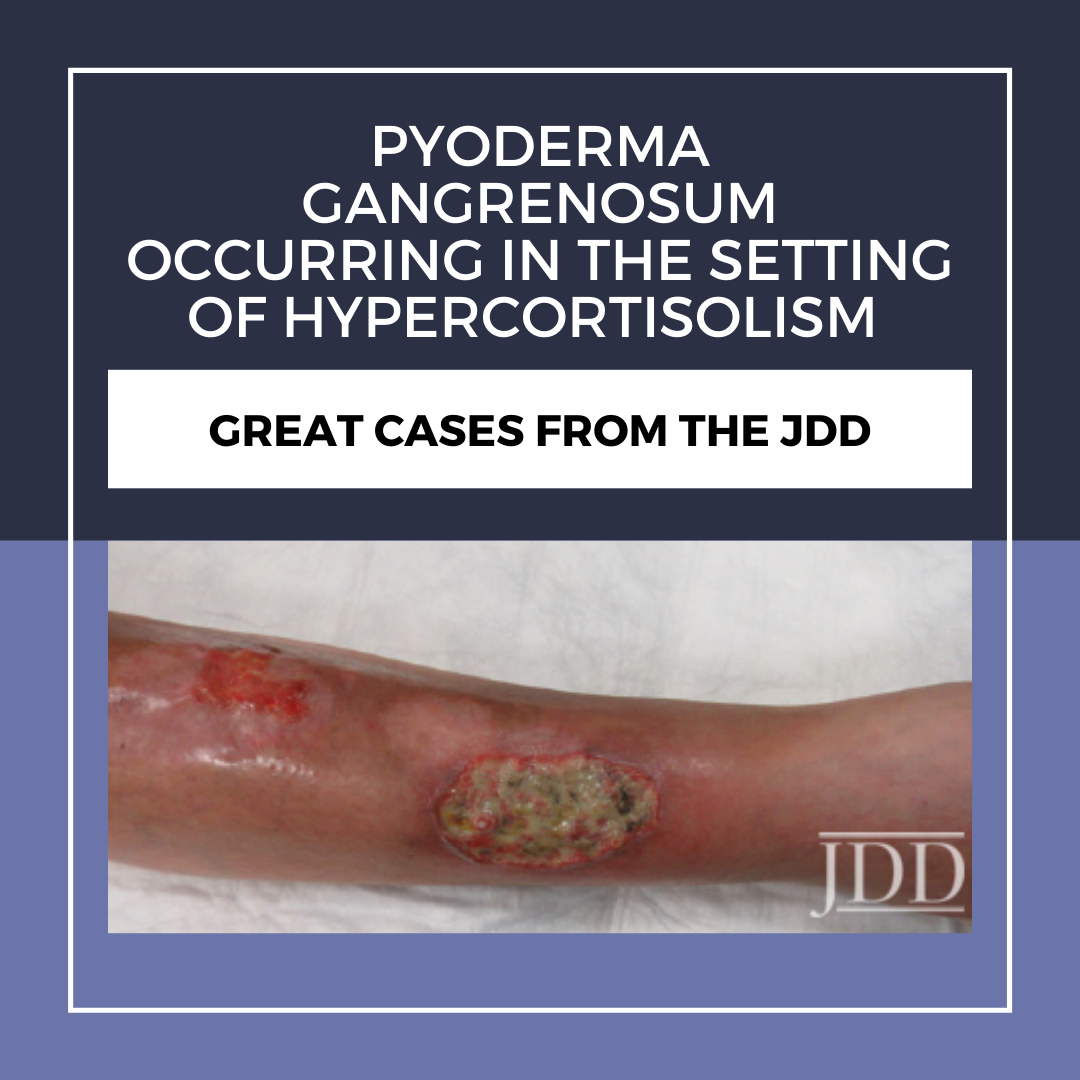

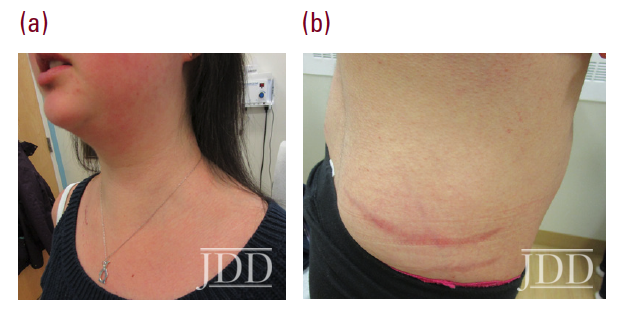

Physical examination revealed facial plethora, moon facies, supraclavicular fat pads, macular purpura on the bilateral upper extremities, truncal wide, purple striae, increased fine hair without terminal hair growth along her upper back, anterior clavicle, and neck (Figures 1a, b). Her left, distal, anteromedial lower leg had two cribriform scars from previous ulcers and her right distal anterior lower leg had two active ulcerations (Figure 2). Given the prior lack of response to systemic steroids, the patient started on cyclosporine 4 mg/kg daily for one month with limited to no improvement on wound closure no improvement on wound closure, at which time it was discontinued as a re- sult of new onset hypertension, and changed to mycophenolate mofetil (1000mg twice daily). Prior to taking cyclosporine, she never had a history of hypertension. Her active wounds were treated with local wound management, which included Santyl, dapsone, and bandaging with xeroform, non-adherent dressing, and Coban wrap.

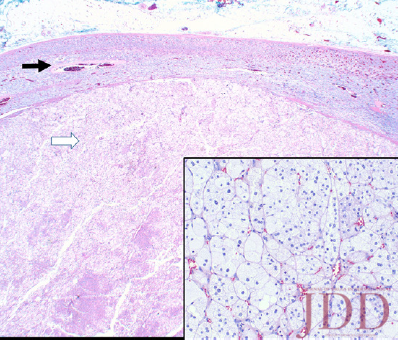

Simultaneously, given her history and physical signs, concomitant Cushing’s syndrome was suspected, and the patient was referred for endocrinology consultation. Laboratory testing revealed low serum adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels, elevated serum cortisol levels, elevated 24-hour urine cortisol levels, and failure to suppress on a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. This was consistent with an ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome. Abdominal CT-imaging revealed a 2.8cm x 2.6cm adrenal nodule that enhanced with contrast, consistent with an adrenal adenoma. She proceeded to have an adrenalectomy and an adrenocortical adenoma was confirmed by surgical pathology (Figure 3). Post-operatively, the patient was given a protracted hydrocortisone taper over 14 months that was titrated in response to constitutional symptoms. The patient’s PG wounds rapidly resolved within a month and mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued 2 months post-adrenalectomy

Discussion

Many comorbidities have been associated with PG, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), various arthritides, hematologic abnormalities and malignancies, hidradenitis suppurativa, systemic lupus erythematosus, and HIV; it is important to solicit a comprehensive review of systems and perform a workup for underlying disease in the setting of PG.1Although the first-line treatment option for large, progressive PG is systemic corticosteroids, treatment of the underlying disease is also important in PG management.1 For our patient, a thorough workup was not performed for any underlying disease, such as undiagnosed IBD or irritant dermatitis, before presenting to our clinic since she was on a prednisone taper.

Interestingly, there are only a few case reports documenting an association between PG and Cushing’s syndrome, a disease that manifests from excess endogenous production of corticosteroids.2,3 De Silva and colleagues reported a 38-year old female that had PG and Cushing’s disease, which both had resolved after removal of a pituitary microadenoma.2 Cole and colleagues reported a 55-year old female that also had PG and Cushing’s syndrome, which both had resolved rapidly with a subsequent disease-free course after removal of an adrenocortical carcinoma.3 Similar to these previous studies, our patient had rapid improvement of both PG and Cushing’s syndrome following removal of an adrenocortical adenoma. As PG has been associated with malignancy, the tumor microenvironment of the patient’s adrenocortical adenoma may have contributed to both her PG and Cushing’s Syndrome through the production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α, a key proponent of PG pathogenesis.1,4,5) In a review by Zhang and colleagues, the inflammatory microenvironment is an important part of the tumor microenvironment, contributing to inflammatory-induced tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis.4 TNF-α is one of the inflammatory cytokines important for mesenchymal stem cell tumorigenesis via the NFkB pathway, and inducing epidermal-mesenchymal transition in certain cancer cell types despite also having antineoplastic roles physiologically.4 Thus, TNF-α may be the potential link between malignancy and PG.

Additionally, our patient’s hypercortisolism may have been involved in maintaining an inappropriately high TNF-α state that exacerbated her PG. In a review article, Valassi and colleagues proposed that the physiologic interplay between cortisol and TNF-α is altered in a hypercortisolism state such that TNF-α levels are inappropriately high from in vivo studies.5 Other in vivo and in vitro studies and shown that administration of corticotropin-releasing hormone increased TNF-α levels in the culture mediums of ACTH-secreting tumors.6 Thus, it may be possible that the resolution of her Cushing’s syndrome terminated incessant TNF-α systemic production and resolved her PG.

While our patient was exposed to exogenous steroids previously, given the duration of symptoms, recalcitrance of disease to common treatment algorithms, and ultimate resolution following surgical intervention, the adrenocortical adenoma was likely the source of her PG, highlighting the rare nature of this presentation. In sum, this case highlights the importance of considering PG occurring in the setting of hypercortisolism secondary to an adrenocortical adenoma even amidst the apparent pathophysiologic paradox.

Disclosures

References

-

- Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(3):191-21.1

- De Silva B, Doherty VR. Coexistence of pyoderma gangrenosum and Cushing’s disease: a paradoxical association? Br J Dermatol. 2002;142(5):1051- 1052.

- Cole HG, Nelson RL, Peters MS. Pyoderma gangrenosum and adrenocortical carcinoma. Cutis. 1989;44(3):205-208.

- Zhang S, Yang X, Wang L, et al. Interplay between inflammatory microenvironment and cancer stem cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(1):679-686.

- Valassi E, Biller BMK, Klibanski A, et al. Adipokines and cardiovascular risk in cushing’s syndrome. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(3):187-206.

- Merola B, Longobardi S, Colao A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases after corticotropin-releasing hormone administration in Cushing’s disease. In vivo and in vitro studies. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;64(5):393-397.

Source

Wei, Chapman, et al. “Pyoderma Gangrenosum Occurring in the Setting of Hypercortisolism Associated With Adrenocortical Adenoma: A Pathophysiological Paradox.” Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD 20.1 (2021): 95-97.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this case report? You can find more here.