Treating scarring alopecias in patients with skin of color requires a nuanced understanding of their unique clinical features and challenges. Dr. Susan Taylor, Professor of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine (@drsusantaylor), President-Elect of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), and founder of the Skin of Color Society, has devoted her career to improving care for these populations. In her highly informative presentation at the 2024 Skin of Color Update, Dr. Taylor offered invaluable insights into the diagnosis and management of scarring alopecias. Her presentation highlighted the importance of identifying key clinical and dermoscopic patterns, recognizing common comorbidities, and tailoring treatments to address the specific needs of patients with skin of color. She covered critical conditions such as central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, lichen planopilaris, frontal fibrosing alopecia, and traction alopecia, focusing on how to optimize outcomes for this underserved patient group.

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia (CCCA)

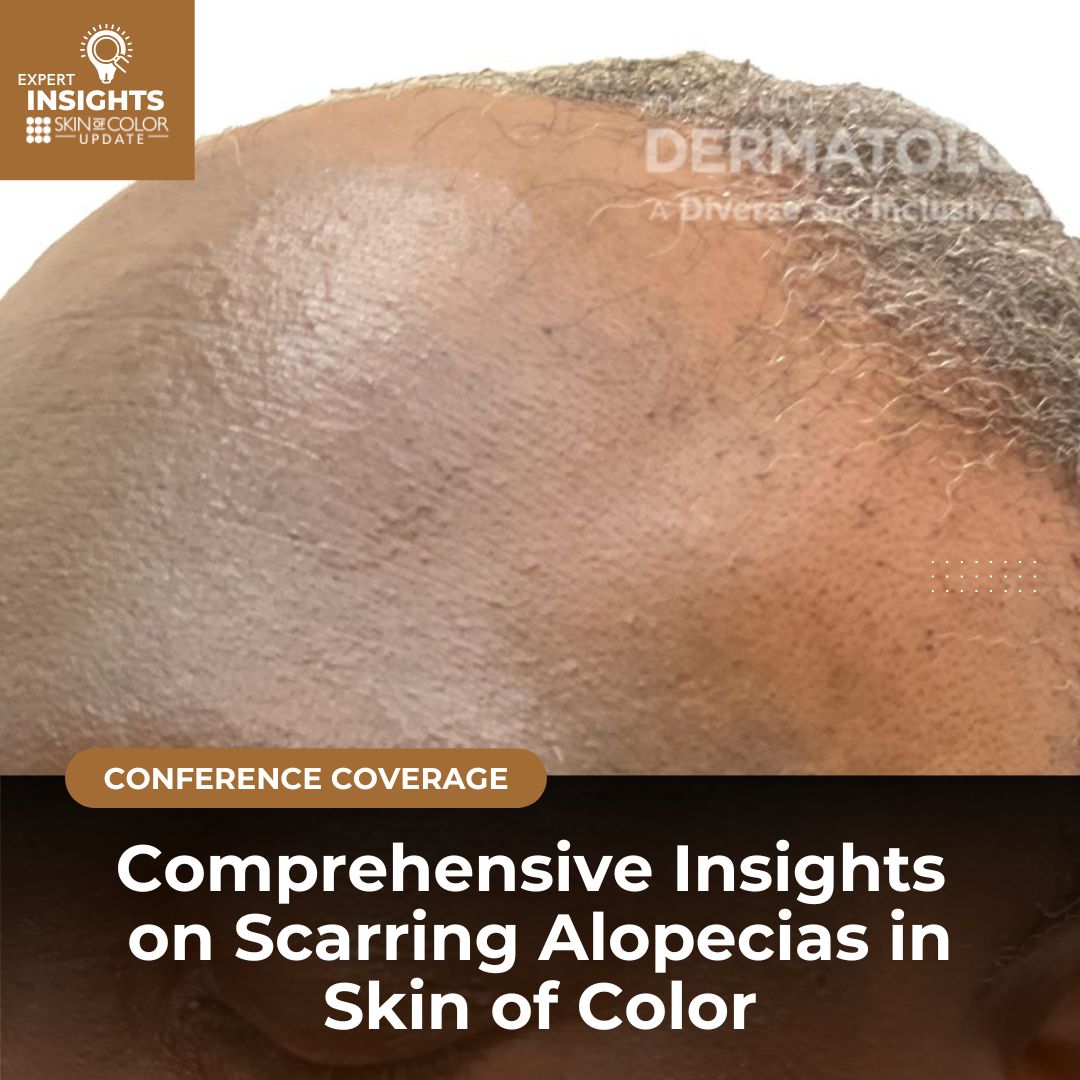

Clinical Features: CCCA is a common cause of scarring alopecia in patients of African descent, and while it most commonly affects the central or vertex scalp, Dr. Taylor pointed out that nearly 28% of patients have atypical distributions, including patchy hair loss in occipital, frontal, temporal, and parietal areas.1 Men with CCCA are often underdiagnosed due to its similarity to androgenetic alopecia (AGA).1,2 Clinicians should consider CCCA in men of African descent presenting with hair loss and pursue both dermatoscopic and biopsy evaluations for proper diagnosis.2

Dermoscopic Features3:

-

- Honeycomb pigmented network

- Terminal and vellus hair changes

- Peripilar white halos (0.3-0.5 mm white or gray circles around hair follicles)

- Pin-point white dots

- White patches, erythema, scales

- Asterisk-like brown blotches

- Broken hairs and dark peri-pilar halos

- Starry sky pattern (interfollicular, irregularly distributed small white macules)

Dr. Taylor also addressed the association between CCCA and systemic conditions, such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes, allergic rhinitis, anxiety, vitamin D deficiency, and breast cancer.4 Recognizing these comorbidities is crucial in providing comprehensive care to patients with CCCA.

Lichen Planopilaris

Clinical Features: Lichen Planopilaris (LPP) is a significant scarring alopecia with several variants, including Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia (FFA) and Lassueur-Graham-Little-Piccardi syndrome. The clinical course of LPP can range from gradual to rapid hair loss, presenting with perifollicular violaceous erythema and scaling. The hair loss pattern is variable, and patients often exhibit several scattered areas of partial hair loss.

Dermoscopic Features5:

-

- Perifollicular hyperkeratosis (thickening of the follicular opening)

- Perifollicular erythema (redness around the hair follicle)

- Hypo- or depigmented scarred-down plaques, which are especially noticeable in patients with darker skin tones.

Dr. Taylor also emphasized the importance of examining the entire body, as lichen planus of the skin, nails, and mucous membranes may manifest before or after scalp involvement. Clinically, patients with LPP often report a burning sensation on the scalp, in contrast to the tenderness and itching more commonly associated with CCCA. Although these symptom distinctions are based on clinical experience, more studies are needed to confirm these observations.

Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia

Clinical Features: Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia (FFA) is a variant of LPP that primarily affects women, though it can also occur in men. Dr. Taylor noted that FFA presents as a symmetric band of hair loss along the anterior hairline, which gradually spreads posteriorly. Early signs of FFA include thinning or absent eyebrows, which may precede scalp involvement, and facial skin changes such as non-inflammatory papules and macular hyperpigmentation, particularly in patients with skin of color.6 Additional clues to diagnosis could include depression of the frontal vein, absence of forehead wrinkles, as well as preauricular skin folds.6

Dermoscopic Features7:

-

- Lonely hair sign (isolated hairs spared at the anterior hairline)

- Perifollicular hyperkeratosis

- Perifollicular erythema

- Macular hyperpigmentation, especially in darker skin types.

Dr. Taylor described atypical patterns of hair loss in FFA, including diffuse, zigzag, pseudo-fringe, ophiasis-like, and androgenetic alopecia-like patterns.8 An important nuance Dr. Taylor addressed is the involvement of other body sites in FFA. While scalp hair loss is common, FFA can extend to the eyebrows, sideburns, and even body hair. In men, sideburn loss may be the sole presenting feature.9 Dr. Taylor discussed a case of a male patient with FFA who experienced progressive recession of his fronto-parietal hairline along with patchy hair loss on the beard and limbs.10 Dermoscopy in such cases revealed loss of follicular orifices, peripilar erythema, and white concentric scales.

She also discussed the association between FFA and actinic damage (sun-related damage), raising the possibility that sunscreen use may be linked to FFA. A study highlighted in her presentation hypothesized that FFA might not be directly caused by sunscreen ingredients, but rather that actinic damage could play a role in the condition.11 Dr. Taylor also mentioned patch testing for chemicals found in sunscreens and hair products, such as cetrimonium bromide and drometrizole trisiloxane, which may help uncover potential allergens linked to FFA.12

Traction Alopecia

Clinical Features: Traction alopecia (TA) is caused by prolonged tension on the hair follicles due to hairstyles that pull tightly on the scalp. It is common among people who wear high-tension hairstyles such as braids, buns, ponytails, and extensions.7 TA primarily affects the frontal and temporal hair margins, but it can also involve the occipital area. Early symptoms include scalp tenderness, erythema, and sometimes follicular papules or pustules. As TA progresses, patients may experience permanent hair loss if the tension continues.

Dermoscopic Features7,13-14:

-

- Fringe sign (retained hair along the frontotemporal hairline, distinguishing TA from FFA)

- Broken hairs

- Black dots

- Flambeau sign (white tracks resembling a torch in the direction of hair pull)

- Hair casts (cylindrical encasements around proximal hair shafts).

Dr. Taylor emphasized that early recognition of TA and hairstyling modifications can halt the progression of hair loss. She recommended that clinicians obtain a comprehensive hairstyling history to assess risk factors for TA and provide guidance on protective hairstyling practices to improve patient outcomes and strengthen patient-provider relationships.

Conclusion

Dr. Taylor’s presentation provided an in-depth exploration of scarring alopecias in patients with skin of color, with a focus on the unique clinical and dermoscopic features of conditions like CCCA, LPP, FFA, and TA. Her discussion highlighted the importance of recognizing these distinct patterns, comorbidities, and diagnostic challenges to improve care for these often underdiagnosed conditions. The detailed insights into each condition’s presentation, as well as the role of dermoscopy, provided valuable guidance for dermatologists.

References

-

- Sow YN, Jackson TK, Taylor SC, Ogunleye TA. Lessons from a scoping review: Clinical presentations of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91(2):259-264. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.009

- Jackson TK, Sow Y, Ayoade KO, Seykora JT, Taylor SC, Ogunleye T. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia in males. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(6):1136-1140. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.07.1011

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):443-449. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.069

- Leung B, Lindley L, Reisch J, Glass DA 2nd, Ayoade K. Comorbidities in patients with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: A retrospective chart review of 53 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(2):461-463. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.013

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28(1):3-10. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.006

- Melo DF, de Mattos Barreto T, de Souza Albernaz E, Haddad NC, Tortelly VD. Ten clinical clues for the diagnosis of frontal fibrosing alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85(5):559-564. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_713_17

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5(5):314-319. Published 2019 Aug 22. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Lis-Święty A, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a disease that remains enigmatic. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(4):482-489. doi:10.5114/ada.2020.98241

- Pathoulas JT, Flanagan KE, Walker CJ, et al. A multicenter descriptive analysis of 270 men with frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(4):937-939. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.060

- Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Moreno-Gimenez JC, Camacho-Martinez FM. Beard involvement in a man with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(6):542-544. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.144183

- Porriño-Bustamante ML, Montero-Vílchez T, Pinedo-Moraleda FJ, Fernández-Flores Á, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Arias-Santiago S. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia and Sunscreen Use: A Cross-sectional Study of Actinic Damage. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00757. Published 2022 Aug 11. doi:10.2340/actadv.v102.306

- Pastor-Nieto MA, Gatica-Ortega ME, Borrego L. Sensitisation to ethylhexyl salicylate: Another piece of the frontal fibrosing alopecia puzzle. Contact Dermatitis. 2024;90(4):402-410. doi:10.1111/cod.14463

- Shim WH, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Dermoscopic approach to a small round to oval hairless patch on the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(2):214-220. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.2.214

- Mayo TT, Callender VD. The art of prevention: It’s too tight-Loosen up and let your hair down. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(2):174-179. Published 2021 Jan 29. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.019

This information was presented by Dr. Susan Taylor during the 2024 Skin of Color Update conference. The above session highlights were written and compiled by Dr. Nidhi Shah.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more here.