Physicians from throughout the Washington DC area recently convened at the Georgetown University MedStar Washington Hospital Center Hair Disorders Symposium, where distinguished experts in the field of hair disorders discussed the evaluation, work-up, and treatment of a wide variety of alopecias and scalp disorders. A treasure trove of clinical pearls was shared along the way, and the attendees learned a host of new strategies to apply to the management of hair loss, which is both widely prevalent and frequently undertreated.

This post is the first of a multi-part series that summarizes salient points from each of the lectures, as well as strategies that physicians can add to their alopecia armamentarium.

This post is devoted to Dr. Leslie Castelo-Soccio’s lecture, “Clinical approach to hair loss in pediatric patients.” Dr. Castelo-Soccio is a pediatric dermatologist as well as the Dermatology Section’s Director of Clinical Research at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She is an expert in alopecia as well as genetic skin disease. Her lecture provided an incredibly useful roadmap for residents learning to navigate the following aspects of caring for the pediatric alopecia patient:

- History-taking

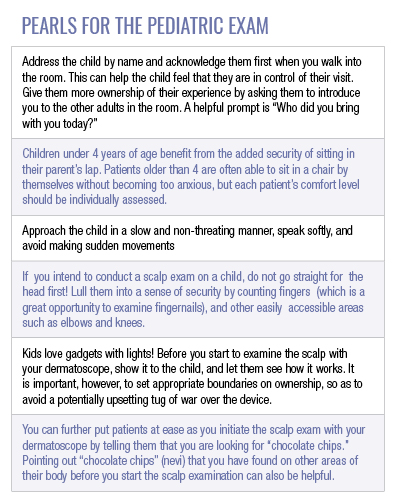

- Physical examination

- Treatment options, with a special focus on JAK inhibitors

- “By the way…” questions

- Biotin

- Gluten-free diet

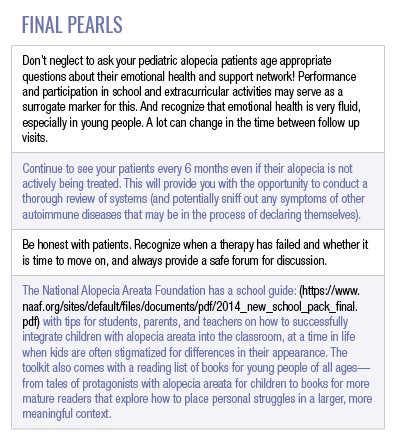

- Clinical Pearls!!

History-taking

A key etiological branch point to touch upon on early when obtaining an alopecia history is whether the condition may be attributable to an acquired autoimmune disorder, or to a genodermatosis (hypotrichosis, ectodermal dysplasia, etc.). This can be discerned by asking the patient’s parents:

- Was there hair at birth?

- Did they ever get their hair?

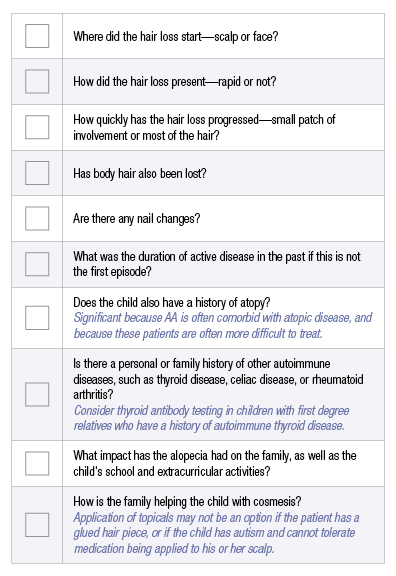

Genodermatoses will usually present before 2 years of age. If the hair loss seems more likely attributable to alopecia areata (AA), additional questions can be directed towards understanding the behavior of the patient’s disease and how this may impact response to treatment, risk stratification for other autoimmune diseases that often cluster with AA, the psychosocial impact of the disease, as well as how unique patient characteristics may influence treatment options. Some of these questions include:

As the aforementioned questions attest, there is a wealth of information to be gathered from the history portion of the encounter. A diagnosis that has not fully emerged from the history can be further pursued with a careful physical exam, which should always involve the use of dermoscopy. Features that support a diagnosis of AA include:

- Miniaturization of hairs, with diffuse miniaturization suggesting AA

- Presence of follicular ostia, with yellow dots or black dots

- Exclamation point hairs, which suggest active disease

- Pigtail hairs, which suggest regrowth and treatment efficacy

- Also a useful finding when providing reassurance to families

In addition to the dermoscopic exam, the total area involved and pattern of alopecia (patchy, diffuse, ophiasis, sisaipho, totalis) should be assessed. A positive pull test can help indicate whether the disease is active. Eyebrows (head vs body vs tail) and eyelashes should be examined for involvement. Regrowth should also be examined, and the color of any newly growing hairs noted, though it is not clear at this time whether and how regrowth color can be used as a prognostic tool.

Medical therapy

There is no one-size-fits all treatment plan for the pediatric AA patient. Therapy should instead be tailored to suit the patient’s age (ex. scalp injections in children younger than 12 can be traumatizing), hair characteristics (ex. avoid heavy ointments in fine hair), duration of hair loss, and disease activity. Topical steroids are first line therapy for most patients and are used in conjunction with intralesional steroid injections when the patient is old enough to tolerate it. Systemic corticosteroids may be pulse dosed or delivered in short courses for new onset and/or rapidly progressing disease.

Methotrexate is another well tolerated systemic option. Topical minoxidil can be considered, though it may lead to unwanted hair growth on the face and hands. For patients with diffuse scalp involvement, or patients who are not able to tolerate injections (younger patients), topical irritants (anthralin, tretinoin) as well as contact sensitizers (DPCP, squaric acid) may also be attempted.

There has been much discussion as of late about the role of JAK inhibitors in the treatment of AA. They are an exciting and promising new therapeutic modality for pediatric AA patients, though many unanswered questions remain about their use in this population. The most important first step to starting an AA patient on a JAK inhibitor is ensuring that the family is extensively educated. It is important to take time to explain how these medications work (simplified diagrams can help), to verify that family members understand that JAK inhibitors are used off-label for AA, that they additionally understand the concept of off-label usage, and that they understand that it is a relatively new treatment for AA in the pediatric population with a paucity of long-term safety data.

A major contraindication to starting a child on a JAK inhibitor is a family who struggles with any of the aforementioned. Once this hurdle has been cleared, tofacitinib at a dose of 5 mg PO BID is commonly used in adolescents aged 13 years and older, though it has been rarely used in children as young as 7. There is variability in response time, but most patients will see at least some hair regrowth within 1 – 6 months of use. It should be noted, however, that relapse with cessation of therapy is common (often within 3 months), and that patients may lose the majority of the hair they regained while on therapy. Laboratory monitoring consisting of CBC, CMP, and lipids should be obtained at baseline, 6 weeks into therapy and, provided that there are no derangements, every 4 – 6 months thereafter. Yearly tuberculosis testing should also be obtained.

Are JAK inhibitors safe??

Several questions remain about the role that JAK inhibitors should play in the treatment of the pediatric AA patient, as well as the long-term safety of these medications. The age at which It is safe to commence treatment with JAK inhibitors is not currently known, we do not know whether these medications possess any disease modifying potential, and we do not know what, if any, are the long-term consequences of using these medications in younger patients. All of this being said, they appear to be well tolerated in the short term.

What about topical JAK inhibitor therapy?

Patients who might not be suitable candidates for systemic therapy with JAK inhibitors may derive benefit from topical formulations. Tofacitinib 2% or ruloxitinib 0.6 – 1%, delivered in a liposomal base, have shown efficacy in some studies. Their use, however, is often limited by their high cost. Because of this, topical JAK inhibitors tend to be reserved for focal areas of alopecia (eyebrows), or an area that has proven recalcitrant to other forms of therapy. Research is also now taking place on using these medications in conjunction with other treatment modalities (ex. excimer laser with tofacitinib). These medications are generally well tolerated and are associated with minimal systemic immunosuppression. For patients who may be good candidates for topical JAK inhibitors, but whose families do not have the means to afford them, compounding pharmacies can sometimes be an option.

“By the way…”

Dermatologists should be prepared to field questions about how vitamin and mineral supplementation, as well as diet, may impact alopecia. One of the most common “by the way” questions—those questions that patients love to slip in as you have one foot out of the clinic room at the end of a visit—concerns the role of biotin (also known as B7 or vitamin H) in the treatment of alopecia.

Can biotin help treat hair loss?

Primary biotin deficiency is rare, with an incidence of around 1 in every 60,000 live births. Secondary deficiency can occur in the setting of pregnancy, anorexia, alcohol abuse, short bowel syndrome, and prolonged isotretinoin use. Although there are no defined standards for what biotin levels should be, most individuals are not biotin deficient. Therefore neither require supplementation, nor benefit from it. For patients who remain unconvinced, a diet that is rich in biotin containing foods—such as nuts, legumes, whole grains, and egg yolks—can be recommended instead. Patients should be provided education on the potential risks that accompany biotin supplementation.

In November 2017, the FDA issued a warning regarding how biotin supplementation may lead to falsely low troponin results. Biotin can also lead to falsely high or falsely low thyroid function tests, depending on the type of assay used. For this reason, biotin should be stopped at least 72 hours and ideally 1 week before testing. This will aid in avoiding inaccuracies in results.

Should I put my child on a gluten-free diet?

Most alopecia will not require, or benefit from, any dietary modifications. Patients with both KNOWN celiac disease and AA, will benefit from a gluten free diet. Not only for the management of their celiac disease, but also for its potential to improve AA. The prevalence of celiac disease in AA patients mirrors that of the general population in North America. That being said, AA patients are not at increased risk of celiac disease UNLESS they have a first degree relative who also has the disease. Patients with known autoimmune diseases such as type I diabetes or thyroid disease, or Down, Turner, or Williams syndrome, may also be at higher risk for celiac disease.

Parents should receive education on the need for both a blood test (tissue transglutaminase) as well as intestinal biopsy for diagnostic confirmation of celiac disease. For many parents, knowledge of the latter in conjunction with appropriate counseling is sufficient to dissuade them from pursuing unnecessary, invasive testing in the absence of other significant historical elements or clinical exam findings suggestive of celiac disease.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series!

Did you enjoy this post? Find other articles on Medical Derm Topics by clicking here.

Main image courtesy of Dr. Adam Friedman.