As dermatologists, we know that not every warm, red, swollen leg represents cellulitis. Chronic venous insufficiency causing stasis dermatitis can present very similarly. While dermatologists are likely able to (in most cases) distinguish between the two conditions, the same cannot always be said of providers outside of our specialty from whom our patients may also be seeking care. Dr. Jeave Reserva and his colleagues in the department of dermatology at Loyola University in Chicago, sought to examine how the outpatient management of stasis dermatitis varied by physician specialty and patient race. This poster stood out to me at the Skin of Color Update because it challenged me to pause and think more deeply about a condition—stasis dermatitis—that is all too easy to glance over or regard as mundane.

Common conditions that we routinely encounter in our daily practice will more often than not have an important, clinically relevant socioeconomic context that the pace of our daily schedules does not always afford us the opportunity to pause and consider. Though we may be rushing among exam rooms with nary a minute for a spare thought, we should nevertheless both endeavor to understand this context, and question how we can alter our own practices for the benefit of those patients who are placed at the disadvantaged end of it. Dr. Reserva’s work has provided me with the impetus to try to change the way I interact with providers in other specialties, as well as with my patients, as we collaborate to appropriately manage chronic venous insufficiency with stasis dermatitis. I hope that it will do the same for you as you read on.

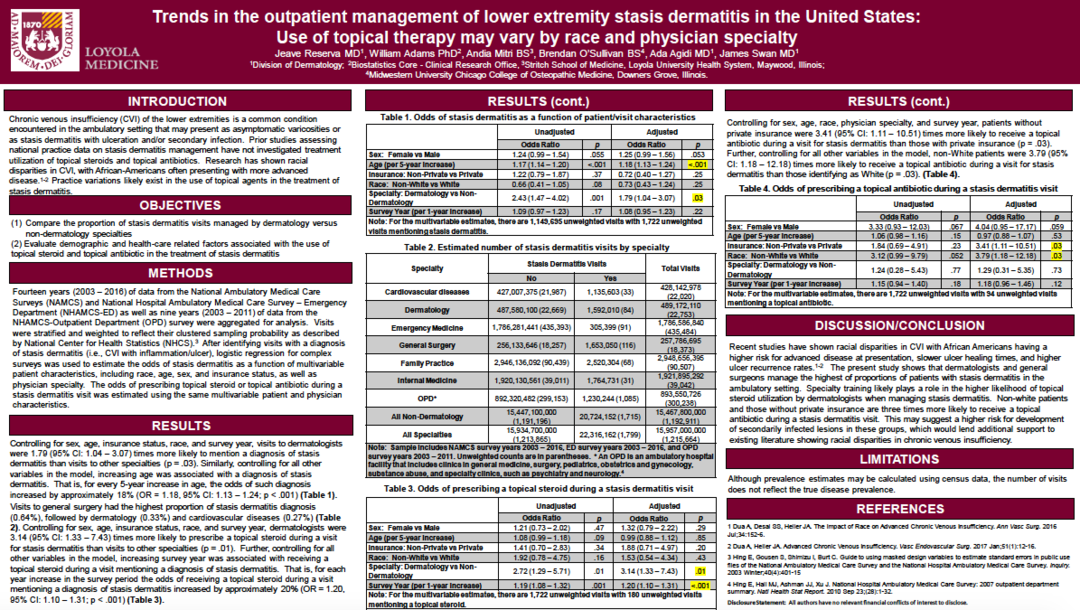

Poster Title: Trends in the outpatient management of lower extremity stasis dermatitis in the United States: Use of topical therapy may vary by race and physician specialty.

-

What prompted you to want to investigate this topic?

My collaborators, namely James Swan, MD and biostatistician William Adams PhD, and I have previously utilized the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) to investigate trends in the management of some of the most common dermatologic conditions. As dermatologists, stasis dermatitis is among the common conditions we encounter in the clinic and, often times get consulted about in the emergency department. Dermatologists are well-trained in identifying cases of chronic venous insufficiency where topical steroids would be of benefit. However, we found that there is limited data in the literature characterizing nationally representative trends in the actual use of topical medications for stasis dermatitis. Furthermore, there is recent evidence highlighting racial disparities in chronic venous insufficiency, with African-Americans presenting with more advanced disease, slower ulcer healing times, and higher ulcer recurrence rates [1,2]. Hence, we aimed to identify practice variations in the use of topical therapy when managing stasis dermatitis.

-

Can you please summarize your key findings?

We reviewed fourteen years (2003 – 2016) of data from the NAMCS and NHAMCS-ED as well as nine years (2003 – 2011) of data from the NHAMCS-OPD and analyzed stasis dermatitis visits using multivariable logistic regression for complex samples [3,4] and identified several key findings. Visits to general surgery had the highest proportion of stasis dermatitis diagnosis (0.64%), followed by dermatology (0.33%) and cardiovascular diseases (0.27%). Controlling for sex, age, insurance status, race, and survey year, dermatologists were 3.14 (95% CI: 1.33 – 7.43) times more likely to prescribe a topical steroid during a visit for stasis dermatitis than visits to other specialties (p = .01). Dermatologists’ keen awareness to the use of topical steroids for stasis dermatitis is likely a result of their unique specialty training. Controlling for all other variables, patients without private insurance were 3.41 (95% CI: 1.11 – 10.51) times more likely to receive a topical antibiotic during a visit for stasis dermatitis than those with private insurance (p = .03). Similarly, non-White patients were 3.79 (95% CI: 1.18 – 12.18) times more likely to receive a topical antibiotic during a visit for stasis dermatitis than those identifying as White (p = .03).

-

What was most surprising to you about your results?

We expected that dermatologists would be more likely to utilize topical steroids when managing stasis dermatitis. Prior studies that have shown racial disparities in chronic venous insufficiency utilized a different national database called the National Inpatient Sample and retrospective single-institution review. Our study used a completely different database, so we were surprised to also identify potential evidence identifying racial and economic disparities in stasis dermatitis treatment.

-

Why do you think non-white patients and those without private insurance are more likely to receive a topical antibiotic during a stasis dermatitis visit?

Stasis dermatitis with ulceration may develop secondary infection signaling more advanced disease and may require the addition of topical antibiotics. We posit that, probably because of health care financial costs, those without private insurance tend to postpone seeking care for their stasis dermatitis thereby presenting with more advanced disease. Although our study combines non-White patients into a single group, our findings also lend additional support to existing literature showing racial disparities in chronic venous insufficiency. Obviously, we make these comments under the assumption that topical antibiotics were being used during these visits because of proven or suspected secondary infection, confirmation of which our methods do not allow.

-

How will the results of your study alter your practice moving forward?

There may be a potential role for dermatologists to educate or remind our colleagues in other specialties about the benefits of incorporating topical steroids in stasis dermatitis management. Additional patient counseling may benefit groups of patients who may be at a higher likelihood of developing stasis dermatitis complications, such as those without private insurance and skin of color patients.

About the Author

Jeave Reserva, MD is a third-year dermatology resident at Loyola University Chicago. His research interests include chemical peels, dermatopathology, and using publicly available databases to investigate resource utilization in dermatologic disease management. Dermoscopy, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color dermatology are among his clinical interests. He would like to thank Dr. Swan and Dr. Adams for their guidance and contributions to this project, and the Division of Dermatology at Loyola University Chicago for the divisional grant that made this study possible.

Jeave Reserva, MD is a third-year dermatology resident at Loyola University Chicago. His research interests include chemical peels, dermatopathology, and using publicly available databases to investigate resource utilization in dermatologic disease management. Dermoscopy, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color dermatology are among his clinical interests. He would like to thank Dr. Swan and Dr. Adams for their guidance and contributions to this project, and the Division of Dermatology at Loyola University Chicago for the divisional grant that made this study possible.

References:

- Dua A, Desai SS, Heller JA. The Impact of Race on Advanced Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jul;34:152-6.

- Dua A, Heller JA. Advanced Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2017 Jan;51(1):12-16.

- Hing E, Gousen S, Shimizu I, Burt C. Guide to using masked design variables to estimate standard errors in public use files of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Inquiry. 2003 Winter;40(4):401-15

- Hing E, Hall MJ, Ashman JJ, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 outpatient department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010 Sep 23;(28):1-32.