INTRODUCTION

CASE

At a follow-up visit one month later, the patient reported resolution of her scalp pain and improvement of involved skin on the trunk and extremities. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the scalp and the body twice daily on weekends and oral doxycycline 20 mg BID twice daily were added to the medication regimen, and topical corticosteroid treatments were restricted to weekdays. However, the patient did not tolerate doxycycline and had scalp irritation with tacrolimus. The patient was then started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. Four months after initiating this regimen, she reported minimal scalp pruritus and significant improvement in her hair loss. The remainder of the skin exam showed residual perifollicular erythema on the trunk and thighs, which had completely resolved by her 12-month follow-up visit.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we presented the case of a patient with GLPLS, a clinical subtype of LPP, which classically features progressive scarring alopecia, axillary alopecia, and lichenoid follicular papules diffusely distributed on the trunk and extremities.3 In conjunction with these findings, patients often report pruritus, burning, or tenderness. A confirmatory skin biopsy is required to make the diagnosis.4 While there are no established therapeutic guidelines specific to GLPLS, the first-line approach for LPP often includes topical or intralesional corticosteroids, albeit with variable success.5 In addition, there are reports of improvement with doxycycline or hydroxychloroquine.6 Our patient experienced limited benefit from topical corticosteroids, which improved scalp tenderness and diffuse follicular erythema but did not halt the progression of alopecia. However, she achieved a significant symptomatic improvement on hydroxychloroquine.

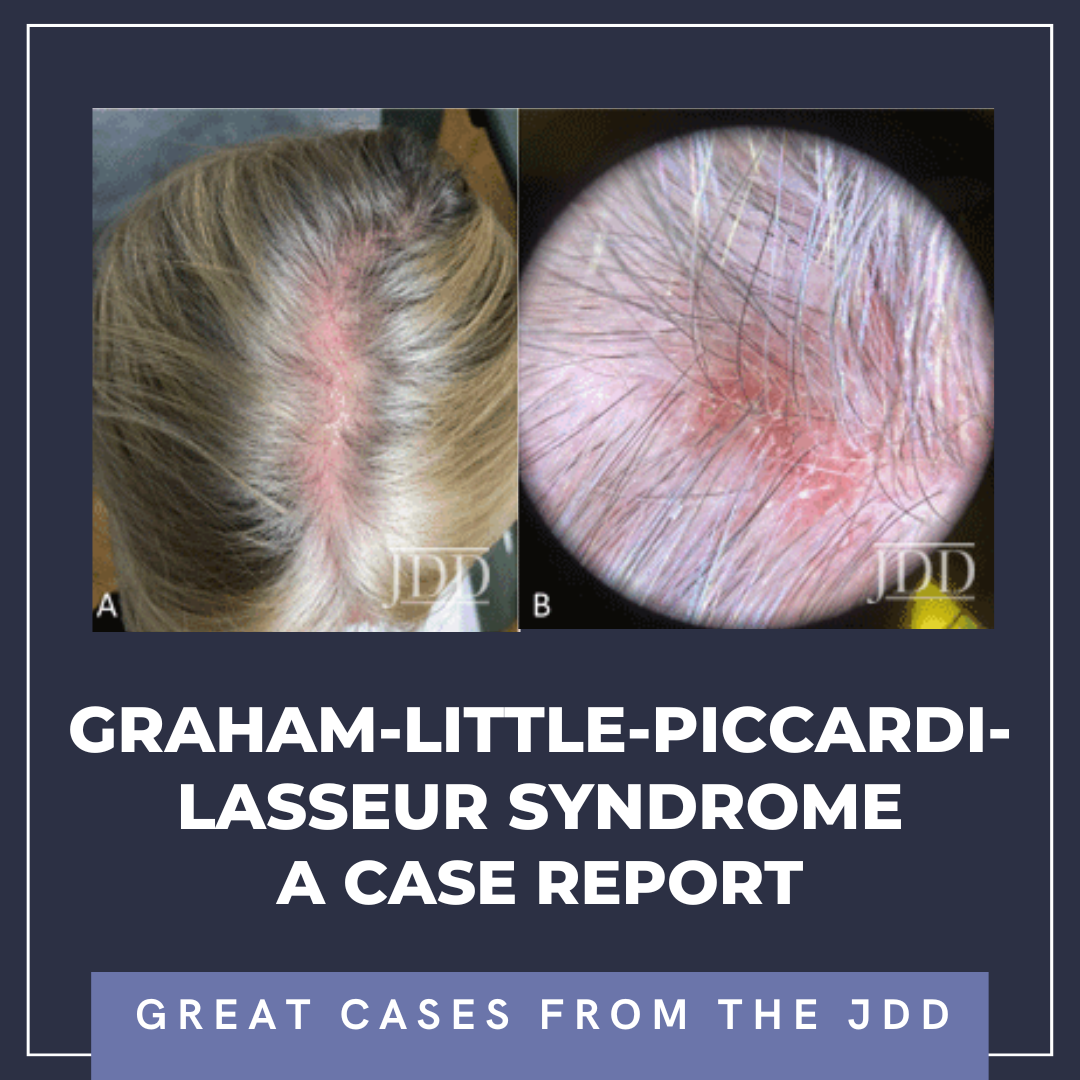

Early recognition of GLPLS, before the development of scarring alopecia, is paramount for therapeutic trials to relieve symptoms and attenuate or potentially halt disease progression. Evaluation of involved skin by dermoscopy can facilitate diagnosis and aid in biopsy site selection. Nonspecific dermoscopic features of cicatricial alopecia include the loss of follicular ostia and the presence of white patches indicative of fibrosis.7 More specifically for LPP, peripilar casts and perifollicular scales can be prominent. A subset of patients with LPP may also present with blue-gray dots, which may correspond to the presence of melanophages.7 Dermoscopic evaluation of our patient revealed decreased hair density, marked erythema with background telangiectasia, peripilar hair casts, and scaling. These findings correlated histopathology with an inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate, perifollicular fibrosis, and follicular plugging.

It is important to distinguish GLPLS from other forms of scarring hair loss. The anatomic distribution of skin lesions in GLPLS is distinct from most other forms of inflammatory cicatricial alopecia including other variants of LPP, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA). Dermoscopically, findings in GLPLS overlap with features of other types of LPP and depend on the stage of the lesion and degree of scarring.8 In contrast to findings in LPP, DLE may feature hyperpigmentation and interfollicular white patches corresponding to interfollicular fibrosis, whereas peripilar white halos are relatively specific to CCCA.9,10 The histologic differential likewise comprises other causes of lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia including LPP variants, DLE, CCCA, and pseudopelade of Brocq (which may represent end-stage scarring of other processes).11

Treatment approaches and prognoses vary among scarring alopecias, and accurate diagnosis is essential for proper counseling and treatment of GLPLS. Early diagnosis may be critical for the timely implementation of interventions prior to the onset of significant scarring, and both dermoscopic and histologic findings are instrumental in supporting a diagnosis of GLPLS. As GLPLS is typically progressive and may have a minimal or variable response to current treatments, patients would benefit from additional treatment options.

DISCLOSURES

REFERENCES

2. Atanaskova Mesinkovska N, Brankov N, Piliang M, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with thyroid disease: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):889-892.

3. Ghislain PD, Van Eeckhout P, Ghislain E. Lassueur-Graham Little-Piccardi syndrome: a 20-year follow-up. Dermatology. 2003;206(4):391-392. doi:10.1159/000069966

4. Shahsavari A, Riley CA, Maughan C. Graham Little Piccardi Lasseur Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2022.

5. Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28(1):3-10. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.006

6. Spencer LA, Hawryluk EB, English JC 3rd. Lichen planopilaris: retrospective study and stepwise therapeutic approach. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(3):333- 334. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.590

7. Duque-Estrada B, Tamler C, Sodré CT, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of cicatricial alopecia resulting from discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(2):179-183. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962010000200008

8. Friedman P, Sabban EC, Marcucci C, et al. Dermoscopic findings in different clinical variants of lichen planus. Is dermoscopy useful? Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5(4):51-55. Published 2015 Oct 31. doi:10.5826/dpc.0504a13

9. Ankad BS, Beergouder SL, Moodalgiri VM. Lichen planopilaris versus discoid lupus erythematosus: a trichoscopic perspective. Int J Trichology. 2013;5(4):204-207. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.130409

10. Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):443-449. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.069

11. Stefanato CM. Histopathology of alopecia: a clinicopathological approach to diagnosis. Histopathology. 2010;56(1):24-38. doi:10.1111/j.1365- 2559.2009.03439.x

SOURCE

Celen, Arda, et al. “Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur Syndrome: A Case Report.” Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD 22.2 (2023): 210-216.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.