Case Scenario

A 26-year-old patient presents to the dermatology clinic with severe nodulocystic scarring acne. The patient identifies as a transgender male and notes that he has been receiving hormone replacement therapy for the past 4 years with weekly intramuscular testosterone injections. He has not had any gender-affirming surgeries and reports being currently amenorrhoeic. He is currently practicing abstinence. The patient has had his gender category legally changed to male on his driver’s license. He reports a long history of moderate acne, which significantly worsened after beginning masculinizing hormonal therapy with testosterone. The patient has tried doxycycline in the past as well as topical therapies including benzoyl peroxide with limited success and is now interested in isotretinoin therapy. The dermatologist notes that iPLEDGE requires physicians to register patients in one of three categories: male, female of non-childbearing potential, or female of child-bearing potential. The dermatologist should:

A. Agree to start the patient on oral isotretinoin and register the patient as “female of childbearing potential” according to the patient’s sex assigned at birth and follow iPLEDGE requirements for “female of childbearing potential.”

B. Agree to start the patient on oral isotretinoin and register the patient as “male” according to their gender identity and legal gender but follow iPLEDGE requirements for “female of childbearing potential.”

C. Agree to start the patient on oral isotretinoin and register the patient as “male” according to their gender identity and legal gender and follow iPLEDGE’s requirements for male patients only.

D. Not offer oral isotretinoin treatment because the category of “male of childbearing potential” does not exist within iPLEDGE’s patient registration schematic.

Discussion

Transgender health has traditionally been neglected in medicine; however, recent interest in improving health care for transgender and other gender diverse persons has greatly increased.1 In the past decade, the medical community has taken steps toward mitigating the barriers to health faced by transgender individuals, and the field of dermatology is increasingly recognizing its critical role in providing non- discriminatory, gender-affirming care for transgender patients.2

The UCLA Williams institute reports there are currently 1.4 million adult Americans who identify as transgender.3 88% of female to male transgender individuals (transgender men) will develop acne within 4-6 months of testosterone administration.2,4 Administration of testosterone can increase levels of androgens at the pilosebaceous unit, leading to androgen-induced sebocyte growth and differentiation as well as increased sebum production and infundibular keratinization.4 This mechanism is thought to underlie testosterone-induced acne given the role elevated sebum excretion plays in acne pathophysiology. Severity of testosterone-induced acne in transgender men is variable, but it can be severe with some patients developing severe inflammatory acne with scarring.5 Typical first line agents for acne such as topical therapies and systemic antibiotics may be insufficient for complete management of testosterone-induced acne, and escalation of treatment is often required.4,5

There are currently no evidence-based best practice guidelines for the treatment of testosterone-induced acne.2 Thus, the treatment escalation algorithm is similar for transgender men and cisgender (non-transgender) individuals, with some key differences.2 Hormonal therapy with spironolactone (aldosterone receptor antagonist with anti-androgen activity) is not appropriate for transgender men who are on hormonal therapy as it could potentially negate the desired masculinizing effects of testosterone therapy.6 Furthermore, hormonal contraceptives such as combined oral contraceptive pills are not indicated for transgender men on masculinizing therapy.7Other contraceptive options are less likely to interfere with masculinizing hormone therapy in transgender men, including intrauterine devices, injectables (Depo Provera), and transdermal implants (Nexplanon), however, these may not necessarily aid in the management of acne vulgaris.6,8 Thus, isotretinoin remains an effective and viable treatment option for testosterone-induced recalcitrant acne. Isotretinoin is highly teratogenic; as a result, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) implemented a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program (iPLEDGE) in 2006 in order to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin and to inform providers as well as patients about the drug’s risks.9 Importantly, pre-menopausal transgender men who have a uterus and ovaries may still become pregnant while undergoing masculinizing hormonal therapy if engaging in vaginal intercourse.10 Registering patients into iPLEDGE mandates that prescribers classify patients into 1 of 3 mutually exclusive categories: male, female of non-childbearing potential, or female of childbearing potential. Females of childbearing potential are required to comply with contraception requirements.

Currently, iPLEDGE does not provide written guidance to providers on how to register transgender individuals. iPLEDGE requires patients to be registered according to sex assigned at birth, which means transgender men must be classified as females.7 This categorization scheme is incongruent with transgender men’s gender identity. Misgendering transgender patients in this manner is a powerful contributor to underlying gender dysphoria, which may contribute to uncomfortable, culturally incompetent clinical encounters, and ultimately lead patients to reject starting treatment with isotretinoin.7

These issues have been raised in the past, with several articles from 2016 to 2019 urging for gender-neutral registration.10-13 A gender neutral patient categorization model of iPLEDGE is also supported by both the American Medical Association (AMA) and American Academy of Dermatology (AAD).14,15 However, despite the pleas from clinicians and patients, no change has yet been made to iPLEDGE.

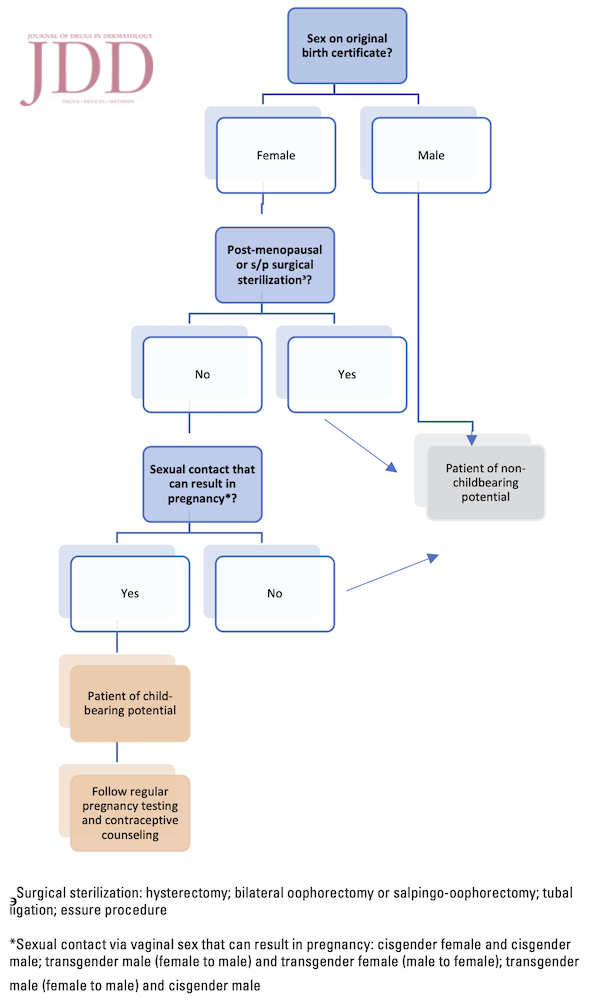

We add our voices to the echo of frustrated providers who find themselves forced to choose between prioritizing their patients’ gender identity and FDA regulations. We agree with gender neutral registration as proposed by the AAD and AMA, and additionally propose assessing for childbearing potential at the time of registration to yield a total of two possible patient registration categories in iPLEDGE: patient of child-bearing potential and patient of non-childbearing potential. We propose the following questions as a guide for providers to follow as part of history taking during the iPLEDGE registration process in order to assess the reproductive potential of their patients in a culturally sensitive manner:

-

- What is your current gender identity?

- What are your chosen pronouns?

- What is the sex listed on your original birth certificate? Male/female (for purposes of identifying childbearing potential)

- Have you ever had any of the surgeries listed below? If so, please specify which procedures

- Hysterectomy (surgery to remove the uterus); bilateral oophorectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy (surgery to remove the ovaries or surgery to remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes); tubal ligation (“tying” of the fallopian tubes); orchiectomy (surgery to remove testicles); vaginoplasty (surgery to remove the penis, scrotum, and testes, and creates a vulva and vagina)

- What is the sex assigned at birth of your sexual partner(s)?

We suggest asking these questions during monthly iPLEDGE visits as the answers to some of these questions may change over time, as patients may change sexual partners and/or may have surgeries later in the course of treatment. Following these proposed parameters, a pre-menopausal transgender male with intact uterus and ovaries who is sexually active with a partner pairing, which can result in pregnancy, would be categorized as a patient of child-bearing potential. This patient would continue to follow iPLEDGE’s requirements and recommendations of pregnancy testing and contraceptive counseling. Conversely, a transgender male with intact pelvic organs who is exclusively sexually active with a partner pairing that cannot lead to pregnancy would be categorized as a patient of non-childbearing potential. Although we focus on transgender patients in this article, similar guidelines may need to be considered for cisgender female patients who are exclusively engaging in intercourse with cisgender females, and thus not at risk of pregnancy. This highlights the importance of taking patient’s sexual orientation and sexual practices into account during iPLEDGE registration as part of a patient-centered approach to care.

Conclusion

None of the current 3 patient categories in iPLEDGE seemed appropriate for our patient, who was a transgender male of childbearing potential. After an open and very frank discussion with the patient, he was required to comply with iPLEDGE’s contraceptive counseling. The patient requested to be registered as “male,” however doing so would result in provider noncompliance and subsequent deactivation from the iPLEDGE system.

We urge the FDA to consider implementing the AAD and AMA’s proposed gender-neutral model of registration for iPLEDGE along with our proposed questionnaire which will allow providers to assess patient’s childbearing potential by elucidating whether a pre-menopausal patient has a uterus and ovaries, and whether the patient is engaging in sexual practices that can lead to pregnancy. This will accurately stratify patients’ risk when taking isotretinoin across all gender identities and types of sexual behaviors. It is important for the field of dermatology to remain on the leading edge of patient safety and advocacy issues and to remain compassionate and adaptable when facing new patient care issues.

Disclosures

Acknowledgment

References

-

- Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):168–171. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000227

- Ragmanauskaite L, Kahn B, Ly B, Yeung H. Acne and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender teenager. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38(2):219–226. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.10.006

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT. (2016). How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in The United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute.

- Motosko CC, Zakhem GA, Pomeranz MK, Hazen A. Acne: a side-effect of masculinizing hormonal therapy in transgender patients. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(1):26–30. doi:10.1111/bjd.17083

- Ginsberg BA. Dermatologic care of the transgender patient. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017; 3:65–7.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb 11].J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945–73.e33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

- Francis A, Jasani S, Bachmann G. Contraceptive challenges and the transgender individual. Women’s Midlife Health 4, 12 (2018). https://doi. org/10.1186/s40695-018-0042-1

- Birth Control and iPLEDGE. https://fenwayhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/ Guide_to_-iPLEDGE.pdf. Accessed on May 15, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/ index.cfm?event=RemsDetails.page&REMS=24. Accessed on April 20, 2020

- Boos MD, Ginsberg BA, Peebles JK. Prescribing isotretinoin for transgender youth: A pledge for more inclusive care. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):169– 171. doi:10.1111/pde.13694

- Mundluru SN, Safer JD, Larson AR. Unforeseen ethical challenges for isotretinoin treatment in transgender patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2(2):46–48. Published 2016 Apr 20. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2016.03.002

- Yeung H, Chen SC, Katz KA, Stoff BK. Prescribing isotretinoin in the United States for transgender individuals: Ethical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol.2016;75(3):648–651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.042

- Katz KA. Transgender Patients, Isotretinoin, and US Food and Drug Administration-Mandated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies: A Prescription for Inclusion. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(5):513–514. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5547

- American academy of dermatology position statement on isotretinoin. https://www.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/ps-isotretinoin.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020

- American medical association gender identity inclusion and accountability in REMS D-100.968. https://policysearch.amaassn.org/policyfinder/detail/ REMS?uri=%2FAMADoc%2Fdirectives.xml-D-100.968.xml. Accessed April 15, 2020

Source

Sanchez, D. P., Brownstone, N., Thibodeaux, Q., Reddy, V., Myers, B., Chan, S., & Bhutani, T. (2021). Prescribing Isotretinoin for Transgender Patients: A Call to Action and Recommendations. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD, 20(1), 106-108.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on LGBTQ+ Care here.