At the 2023 Skin of Color Update, Dr. David Ciocon, Director of Dermatologic Surgery, Mohs Micrographic Surgery (MMS) and Procedural Dermatology at the Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, provided a comprehensive exploration of MMS in patients with skin of color, with a focus on defining keratinocyte carcinoma and shedding light on disparities within this patient population.

His lecture covered the prevalence, varied clinical presentations, and outcomes linked to basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds. In case you couldn’t attend, this article summarizes essential takeaways, underscoring the critical importance of precise nomenclature and increased awareness regarding disparities in skin cancer prevalence and outcomes.

Clarification of Nomenclature

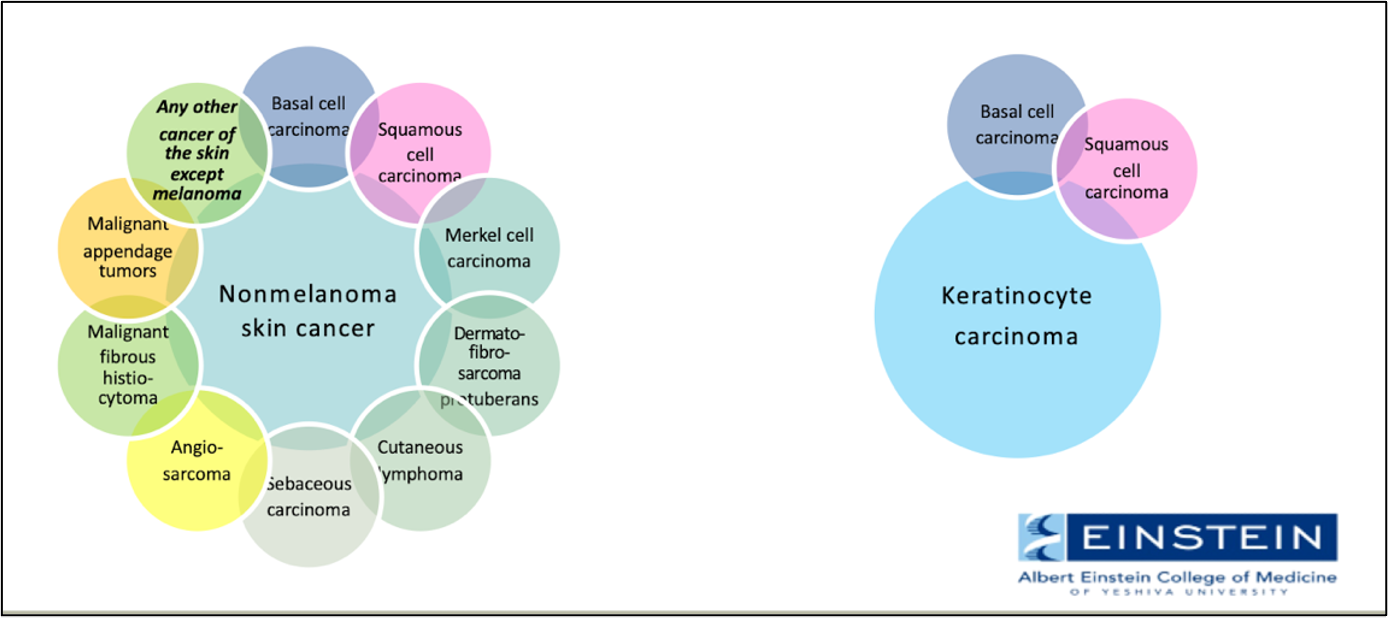

Dr. Ciocon kicked off the lecture by bringing attention to the nomenclature surrounding basal cell (BCC) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). He advocates for the use of the more precise and inclusive term, “keratinocyte carcinoma”, and moving away from the ambiguous term “non-melanoma skin cancer”, which includes many other skin cancers as shown by Figure 1.

Changing Demographics:

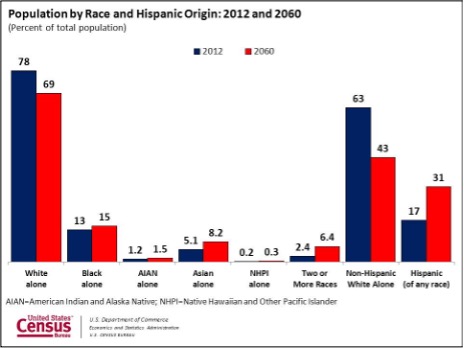

As demographics shift towards a more diverse population, skin cancer prevalence and outcomes are being significantly influenced (Figure 2). By 2060, individuals of color are projected to constitute 57% of the U.S. population, underscoring the urgent need to address the unique features and challenges associated with skin malignancies in this demographic.1

Prevalence by Race and Ethnicity

A 2018 study highlights a 40% prevalence of skin cancer in non-Hispanic white individuals, with lower percentages observed in Hispanic (5%), Asian (4%), and African American (2%) populations.2 Notably, incidences in these groups are on the rise, emphasizing the importance of tailored prevention and early detection strategies.

Specific Trends in Skin Cancer Types

-

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma:

- SCC is the most common skin malignancy in African Americans.

- Chronic inflammatory or scarring processes contribute to 40% of SCC cases in this population. In fact, SCC arising within scars are associated with a 40% metastasis rate. This contrasts sharply with a mere 4% metastasis rate in UV-related SCC cases in white individuals.3

- Basal Cell Carcinoma:

- While BCC is the most common skin cancer in white, Hispanic, and Asian populations, it is the second most common in African Americans. Despite a low metastasis rate, studies consistently show elevated morbidity and mortality in skin of color populations.3,4

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma:

Morbidity and Mortality

Although keratinocyte carcinoma remains less prevalent in skin of color, it is associated with disproportionately higher morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, quantifying morbidity is challenging due to exclusion of relevant data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data. Contributing factors to elevated morbidity include delayed diagnosis, advanced disease at presentation, and limited access to resources. It is crucial to note that keratinocyte carcinoma accounts for more disability-adjusted life years than melanoma.5

Challenges in Research

Studies focusing on Hispanic and African American populations face limitations such as small sample sizes, lack of power, and inconsistent outcome reporting in multicenter studies over several years. Many studies in Hispanic individuals lack characterization by Fitzpatrick skin type.

Clinical Presentation of Keratinocyte Carcinoma

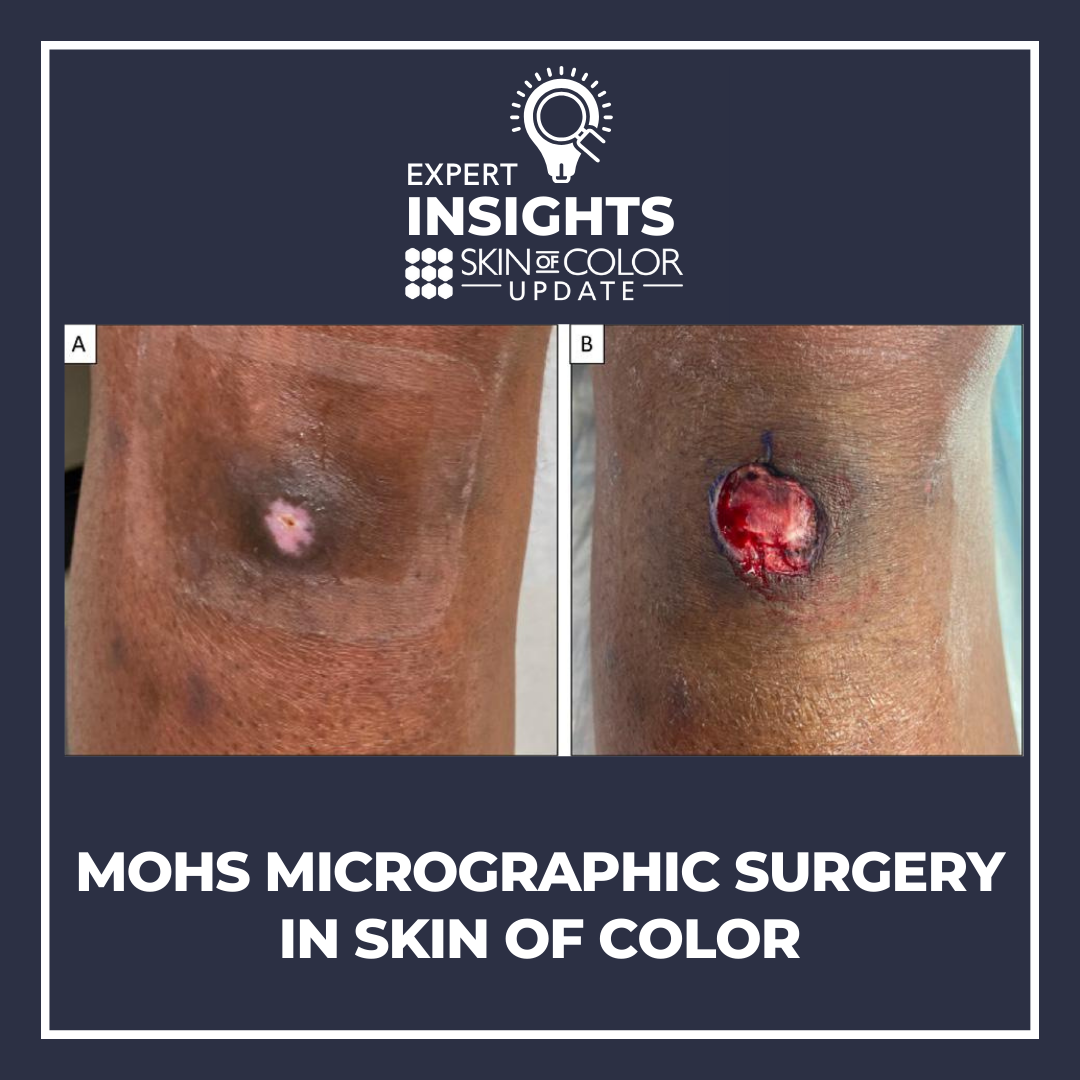

Dr. Ciocon emphasizes the importance of recognizing the common distinctive features of keratinocyte carcinoma in patients of color, such as lesional peripheral pigmentation and excess lichenification. He mentions that primary care physicians are in an ideal position to diagnose keratinocyte carcinoma and educate patients about preventative measures, however, their ability to do so is hindered by the limited representation of skin disease across various skin tones in educational resources and google images.6-10 Another feature to note with keratinocyte carcinomas in skin of color is that there is often significant subclinical extension, which makes MMS a better approach to treatment than traditional excision.

Surgical Outcomes and Complications:

An in-depth analysis of surgical outcomes in MMS for keratinocyte carcinoma in skin of color reveals intriguing disparities.

In Hispanics, flap closures were more common, likely due to the increased occurrence of BCCs in high-risk facial areas, such as the H zone (nose, ear, lips).11 Notably, infundibulocystic BCCs were more common in Hispanic individuals.12 Hispanic patients undergoing MMS for keratinocyte carcinomas were more likely to have larger post-op defect sizes and to require mores stages to achieve clearance.13,14 Differences in MMS outcome was associated with differences in health insurance coverage, with Medicaid and HMO patients have larger defect sizes and PPO patients having smaller defect sizes compared to Medicare.13

In Black patients, presentation of keratinocyte carcinomas occurred at a younger age and was more likely to present as right-sided tumors compared to Hispanic and non-Hispanic White patients.12 Overall, pigmented BCCs presented more frequently in skin of color compared to non-Hispanic White patients.

Finally, postoperative post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) was more common in Fitzpatrick skin types III to VI.15-17 Factors influencing postoperative PIH were explored, including closure type, Mohs stages required, defect size, suture materials, and suture size. Notably, closure by grafts and secondary intent led to a greater risk of PIH, as did the presence of any post-op complication. Higher rates of PIH were also seen in cases requiring more than one Mohs stage and those with defect sizes >100mm2.18

Repairs with Vicryl subcutaneous sutures, absorbable epidermal sutures, or staple closures were associated with greater PIH rates, as was using a larger suture size, such as 3-0 diameter sutures. Taken together, this means you may minimize risk of PIH if you use non-absorbable sutures with smaller diameters and avoid staples. Importantly, the rates of PIH were unaffected by the location of the surgical site.18

Additionally, Dr. Ciocon introduces the potential benefits of intralesional tranexamic acid in reducing bleeding and, potentially, mitigating PIH.

In conclusion, Dr. Ciocon’s comprehensive review underscores the evolving landscape of keratinocyte carcinoma and the unique challenges and considerations associated with Mohs micrographic surgery in skin of color. The ongoing studies promise a deeper understanding of surgical outcomes and potential interventions to reduce complications and disparities in Mohs micrographic surgery for keratinocyte carcinoma. The presentation contributes valuable insights to guide clinicians in providing effective care for this diverse patient population.

References

-

- United States Census Bureau. (2012). U.S. Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. Retrieved January 2, 2024 from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html

- Higgins, S., Nazemi, A., Chow, M., & Wysong, A. (2018). Review of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.], 44(7), 903–910. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000001547

- Gloster, H. M., Jr, & Neal, K. (2006). Skin cancer in skin of color. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 55(5), 741–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.063

- Rubin, A. I., Chen, E. H., & Ratner, D. (2005). Basal-cell carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine, 353(21), 2262–2269. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra044151

- Nehal, K. S., & Bichakjian, C. K. (2018). Update on Keratinocyte Carcinomas. The New England journal of medicine, 379(4), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1708701

- Kurtti, A., Austin, E., & Jagdeo, J. (2022). Representation of skin color in dermatology-related Google image searches. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 86(3), 705–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.036

- Alvarado, S. M., & Feng, H. (2021). Representation of dark skin images of common dermatologic conditions in educational resources: A cross-sectional analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 84(5), 1427–1431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.041

- Lester, J. C., Taylor, S. C., & Chren, M. M. (2019). Under-representation of skin of colour in dermatology images: not just an educational issue. The British journal of dermatology, 180(6), 1521–1522. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17608

- Fathy, R., & Lipoff, J. B. (2022). Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 86(3), e113–e114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Onyekaba, G., Taiwò Née Ademide Adelekun, D., & Lipoff, J. B. (2022). Skin of color representation in dermatology must be intentionally rectified. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 87(1), e43–e44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2022.03.032

- Soliman, Y. S., Mieczkowska, K., Zhu, T. R., Hossain, O., Zhu, T. H., Ciocon, D. H., & Williams, R. F. (2022). Characterizing basal cell carcinoma in Hispanic individuals undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery: a 7-year retrospective review at an academic institution in the Bronx. The British journal of dermatology, 187(4), 597–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21614

- Hossain, O. B., Mieczkowska, K., Srikantha, R., Rzepecki, A., Ciocon, D. H., Hosgood, D., & Williams, R. F. (2023). Keratinocyte carcinoma resected by Mohs micrographic surgery in individuals with skin of color: An observational study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 88(5), 1183–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.022

- Blumenthal, L. Y., Arzeno, J., Syder, N., Rabi, S., Huang, M., Castellanos, E., Tran, P., Pickering, T. A., Dantus, E. J., In, G. K., Soriano, T., & Hu, J. C. (2022). Disparities in nonmelanoma skin cancer in Hispanic/Latino patients based on Mohs micrographic surgery defect size: A multicenter retrospective study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 86(2), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.052

- Juarez, M. C., Criscito, M. C., Pulavarty, A., Stevenson, M. L., & Carucci, J. A. (2023). Characterizing cutaneous malignancies in patients with skin of color treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 89(2), 355–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.018

- Shokeen D. (2016). Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis, 97(1), E9–E11.

- Anvery, N., Christensen, R. E., & Dirr, M. A. (2022). Management of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in skin of color: A short review. Journal of cosmetic dermatology, 21(5), 1837–1840. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14916

- Vashi, N. A., Wirya, S. A., Inyang, M., & Kundu, R. V. (2017). Facial Hyperpigmentation in Skin of Color: Special Considerations and Treatment. American journal of clinical dermatology, 18(2), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-016-0239-8

- Williams, R., & Ciocon, D. (2022). Mohs Micrographic Surgery in Skin of Color. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD, 21(5), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.36849/JDD.6469

This information was presented by Dr. David Ciocon during the 2023 Skin of Color Update conference. The above highlights from his lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Sarah Millan.

Did you enjoy this article? You can find more on Medical Dermatology here.