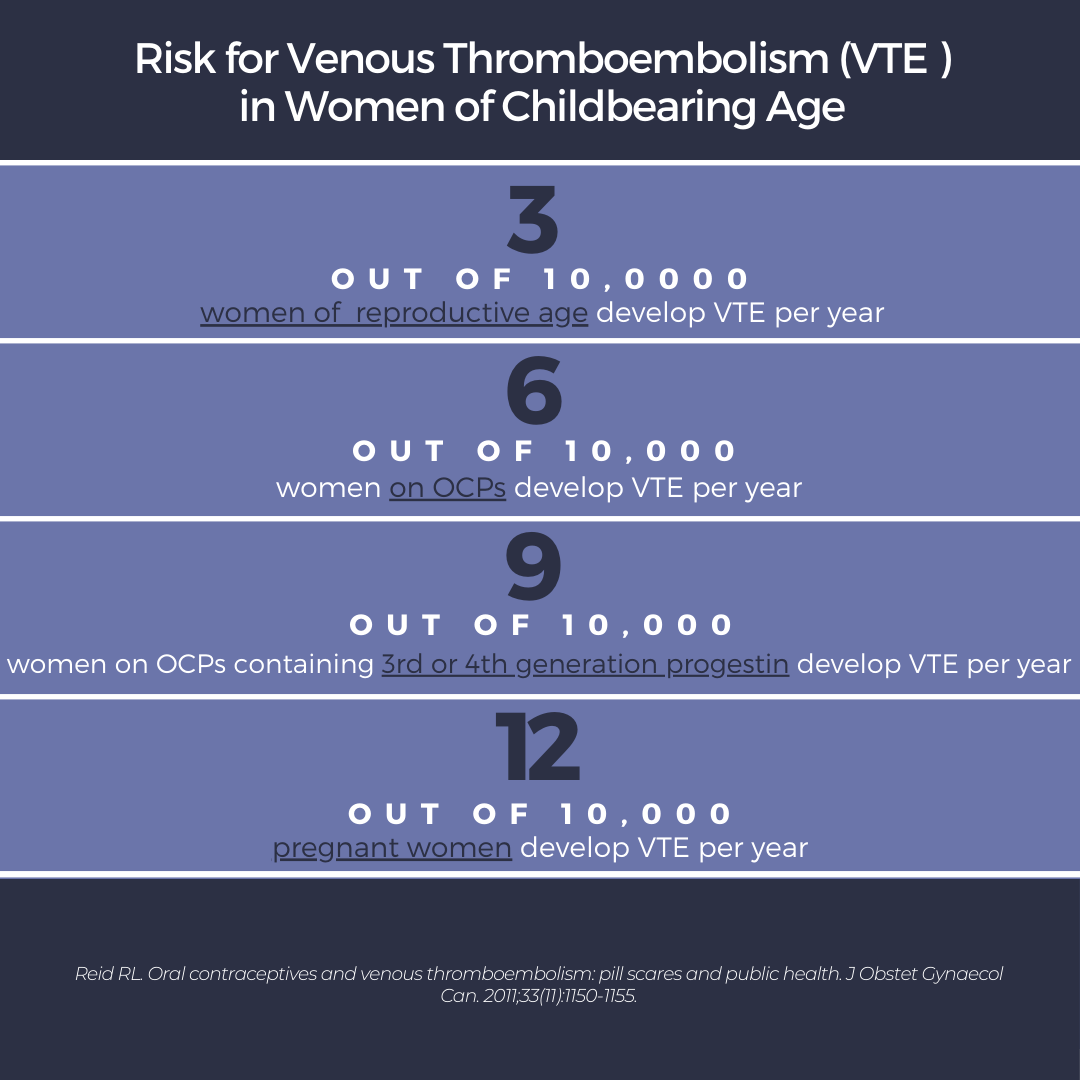

“2, 4, 6, 8… Who do we appreciate?” Dr. Julie C Harper from the Dermatology and Skin Care Center of Birmingham for giving us a rock-solid breakdown of hormonal therapies for acne. Although she didn’t lead us in cheers, she did teach us the “3, 6, 9, 12” of risk for venous thromboembolism in women of childbearing age. Read on to find out more!

Before we get into the “nitty-gritty,” of the bursts of knowledge provided by Dr. Harper, I want to share with you some of my “aha!” moments from her talk:

-

- All Acne is Hormonal. Who should we consider for hormonal therapies in acne? (Spoiler alert) Everyone!

-

- Which Oral Contraceptive Pills (OCPs) work for acne? Answer: probably all of them, as long as they are estrogen + progesterone combined. There are 4 that are currently FDA approved for acne vulgaris and they should only be considered in those who desire

-

- Patients can be on doxycycline and OCPs at the same time! The key antibiotics that interact with OCPs are rifampin and griseofulvin (read below for the article highlighting this factoid).

Now for the details.

What role do hormones play in acne?

The four pillars of acne development are excess sebum production, hyperkeratosis, inflammation, and bacterial proliferation (think: Cutibacterium acnes)1. From a hormonal perspective, acne development is modulated by estrogens and androgens. Androgens stimulate sebum production from sebaceous glands in the skin. Excess sebum and keratinaceous material plug the pilosebaceous unit, forming comedones, the primary lesion of acne. Sebum also promotes the growth of C. acnes. Estrogen, on the other hand, works against androgens and tends to have an inhibitory effect on acne. Estrogen can act locally, by suppressing sebum production on the skin; or centrally, by reducing androgen production in the gonads/adrenals via modulating the negative feedback loop within the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Lastly, estrogen increases sex hormone-binding globulin, which binds androgens, reducing their bioavailability.

Luckily, we have hormonally-based treatment options for acne. These largely include OCPs and oral spironolactone. OCPs contain Ethinyl estradiol plus a progestin. They are estrogen dominant, thus tend to have an overall inhibitory effect on acne, regardless of progestin type. Progestins are defined by different generations, some of which are more androgen stimulatory (lower generations) versus inhibitory (higher generations). Interestingly, a 2014 JAAD meta-analysis demonstrated that the efficacy of OCPs was equivalent to antibiotics after 6 months of use in the treatment of acne, suggesting that OCPs may be considered as a “first line” oral medication for acne2. Spironolactone is an anti-androgen that blocks androgen receptors and decreases androgen synthesis. It is not FDA approved for acne but has been reported for its clinical efficacy. Read below for more deets!

Who do we consider for OCPs?

Dr. Harper began her lecture by calming our inner “lumper” vs “splitter.” We do not need to be splitters when it comes to considering hormonal therapies in patients with acne. She reminded us that all acne is hormonal (think of those androgen receptors in the pilosebaceous unit!). Well, which hormonal therapy do we consider? There are 4 OCPs FDA approved for acne. These are combined estrogen and progestin pills (see below). Although progestins partially activate the androgen receptor, estrogen counters this effect. First-generation progestins act more similarly to androgens than subsequent generations. The fourth-generation progestin drospirenone is analogous to spironolactone, an androgen inhibitor.

Here’s the list of approved OCPs for acne:

-

- Ortho-Tri-Cyclen (ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate): second generation progestin

- Estrostep FE (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone acetate/ferrous fumarate): first generation progestin

- YAZ (ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone): 4th generation progestin

- BEYAZ (ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone/levomefolate): the same as YAZ, just with added folic acid

So what are the risks of OCPs?

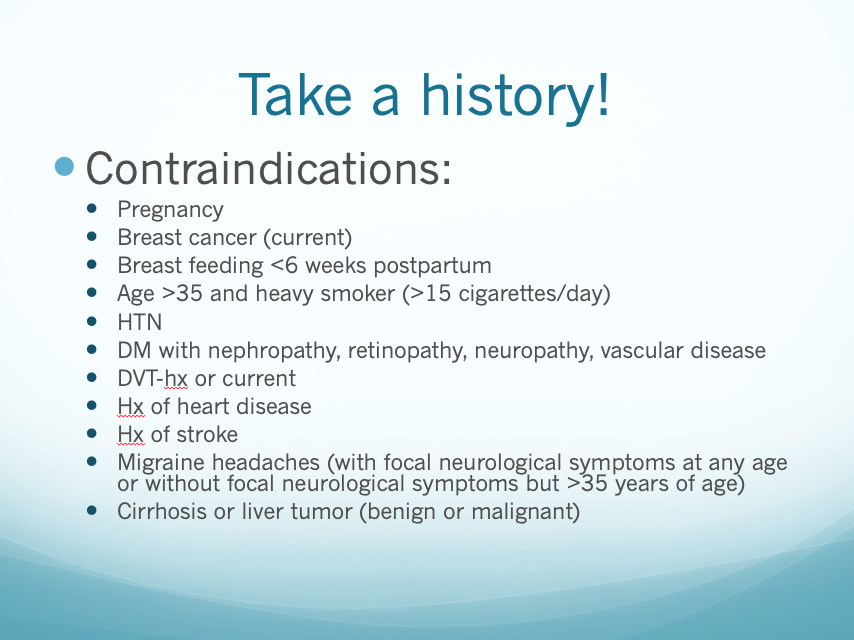

We have to consider the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction, stroke, and breast cancer3. This in contrast to the benefit of pregnancy prevention. In those who desire contraception, OCPs can not only prevent pregnancy but also treat acne. The risk of thromboembolism should be considered in all women on OCPs, but especially those who have other clotting risk factors, such as smoking and age over 354. Dr. Harper does not prescribe OCPs to those with a history of migraine. Unfortunately, the risk of VTE may be increased with higher generations of progesterone (ex. 3rd or 4th generations). Here is where the “3, 6, 9, 12” comes in5:

What do these numbers mean? If women are on OCPs, they are at increased risk of VTE (2-3X the risk of women of reproductive age not on OCPs). However, if a woman becomes pregnant, the risk of VTE quadruples from their baseline. Thus, the use of OCPs in women desiring contraception may be protective against the VTE risk associated with pregnancy. Unfortunately, if a woman is not desiring contraception, the risk of VTE may outweigh the benefit alone of treating acne.

Regarding breast cancer, there is a 20% increased risk of breast cancer in women on OCPs, with increased risk from higher doses and longer duration of use. This persists for 5 years after discontinuation6. However, putting this into perspective, OCPs account for only 1 additional case of breast cancer for every 7,690 women using hormonal contraception in one year. The good news is that OCPs protect against ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine leiomyomas, and ovarian cysts. They also help to regulate the menstrual cycle3.

Prior to starting OCPs, take a thorough patient history and blood pressure reading. Dr. Harper gave a great reference slide for contraindications to OCPs (hint: look below).

Additional points to remember:

-

- Pap smears/bimanual pelvic exams are not mandatory prior to OCP initiation.

- Counsel your patients that it usually takes at least 3 menstrual cycles while on OCPs to see an improvement in acne.

- Doxycycline is safe to take with OCPs. Rifampin and griseofulvin are the main culprit anti-infectives that interact with OCPs.

When thinking about medication interactions, the principal concern with rifampin, among other drugs, is that it induces hepatic enzymes to more rapidly metabolize estrogens and/or progestins in OCPS, thus reducing their serum concentration and overall efficacy7. For more reference material: read the latest and greatest “Practice Bulletin no: 206” from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published February 20198(doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003072).

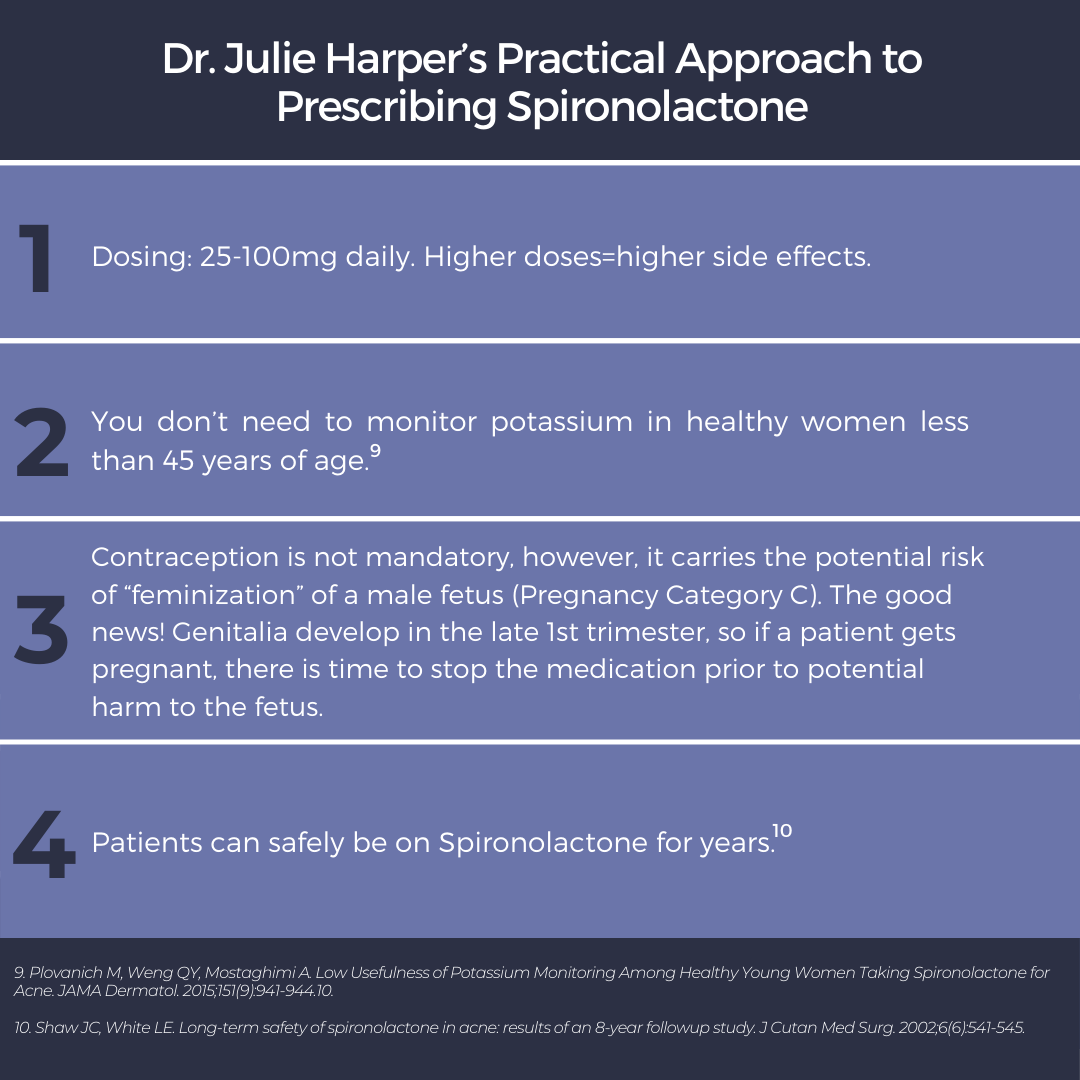

When should we consider spironolactone?

Spironolactone is an anti-androgen commonly used as an adjunctive treatment of “hormonal” acne. Of note, it is NOT FDA approved for this condition. Just like OCPs, it may take 3 months or longer to see an improvement. Side effects include diuresis, menstrual irregularities (which OCPs can help), breast tenderness, breast enlargement, fatigue, headache and dizziness. Here is Dr. Harper’s “Practical Approach” to prescribing spironolactone:

It is important to take into account the patient’s medical history, current prescriptions, and cancer history. Monitor serum potassium if a patient is >45 years of age, or has a history of renal, cardiac, or liver disease. Additionally, there is a black box warning for spironolactone acting as a tumorigen (inducing cancer) in rats given 25-100X the usual human dose11. Fortunately, recent studies have suggested that Spironolactone use in humans may not increase the risk of cancer. A large Danish cohort of 2.3 million women, in whom 1.3 million spironolactone prescriptions were written, was followed for 28.8 million person-years, showing no evidence of increased risk of breast, uterus, or ovarian cancer12. Another matched-cohort study of 1.3 million women aged 55 years or older showed no difference in breast cancer rates in those prescribed spironolactone13. Luckily, our very own Adam Friedman, MD announced a new article that is hot off the press (well… “in-press”) in the JAAD demonstrating no increased risk of breast cancer recurrence in those treated with spironolactone14.

Wow! We made it to the end. So what did we learn?

# 1 Dr. Harper knows her stuff and is a key reference for managing acne (and rosacea!). She is a founding director and president-elect of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

#2 All Acne is hormonal. If considering OCPs or Spironolactone, take a thorough medical history and inquire about current medications. These medications are safe to use for years in the right patient.

#3 There is an increased risk of VTE in women on OCPs, as well as a slightly increased risk of breast cancer, but OCPs are protective against the risks of unwanted pregnancy as well as against other cancers (including ovarian and endometrial).

#4 Spironolactone is not FDA approved for acne but can be a great adjuvant treatment option. We do not need to monitor serum potassium in young healthy women but should stop the medication if it is no longer working, the patient becomes pregnant, or the patient experiences unwanted side effects. Higher doses (> 100mg daily) cause more side effects. There is no current evidence in humans of increased cancer risk from taking spironolactone.

This information was presented by Dr. Harper at the GW Virtual Appraisal of Advances in Acne Conference held July 30th, 2020.

References:

-

- Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379(9813):361-372.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):450-459.

- Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(4 Suppl):S5-22.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(3):CD010813.

- Reid RL. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: pill scares and public health. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(11):1150-1155.

- Morch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard O. Contemporary Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228-2239.

- Hersh EV. Adverse drug interactions in dental practice: interactions involving antibiotics. Part II of a series. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130(2):236-251.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 206: Use of Hormonal Contraception in Women With Coexisting Medical Conditions: Correction. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(6):1288.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low Usefulness of Potassium Monitoring Among Healthy Young Women Taking Spironolactone for Acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year followup study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6(6):541-545.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral Spironolactone in Post-teenage Female Patients with Acne Vulgaris: Practical Considerations for the Clinician Based on Current Data and Clinical Experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5(3):37-50.

- Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(6):870-875.

- Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, Morant S, Wei L. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447.

- Wei C, Bovonratwet P, Gu A, Moawad G, Sculco PK, Silverberg JI, Friedman AJ, Spironolactone use does not increase the risk of female breast cancer recurrence: A retrospective analysis, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2020), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.081

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Medical Dermatology topics here.