INTRODUCTION

CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of hypothyroidism, well controlled on Synthroid 100 mcg daily, presented to our clinic with significant hair shedding and scalp flaking occurring over the previous 10 months. She did not report any associated scalp pain, pruritus nor mucosal lesions.

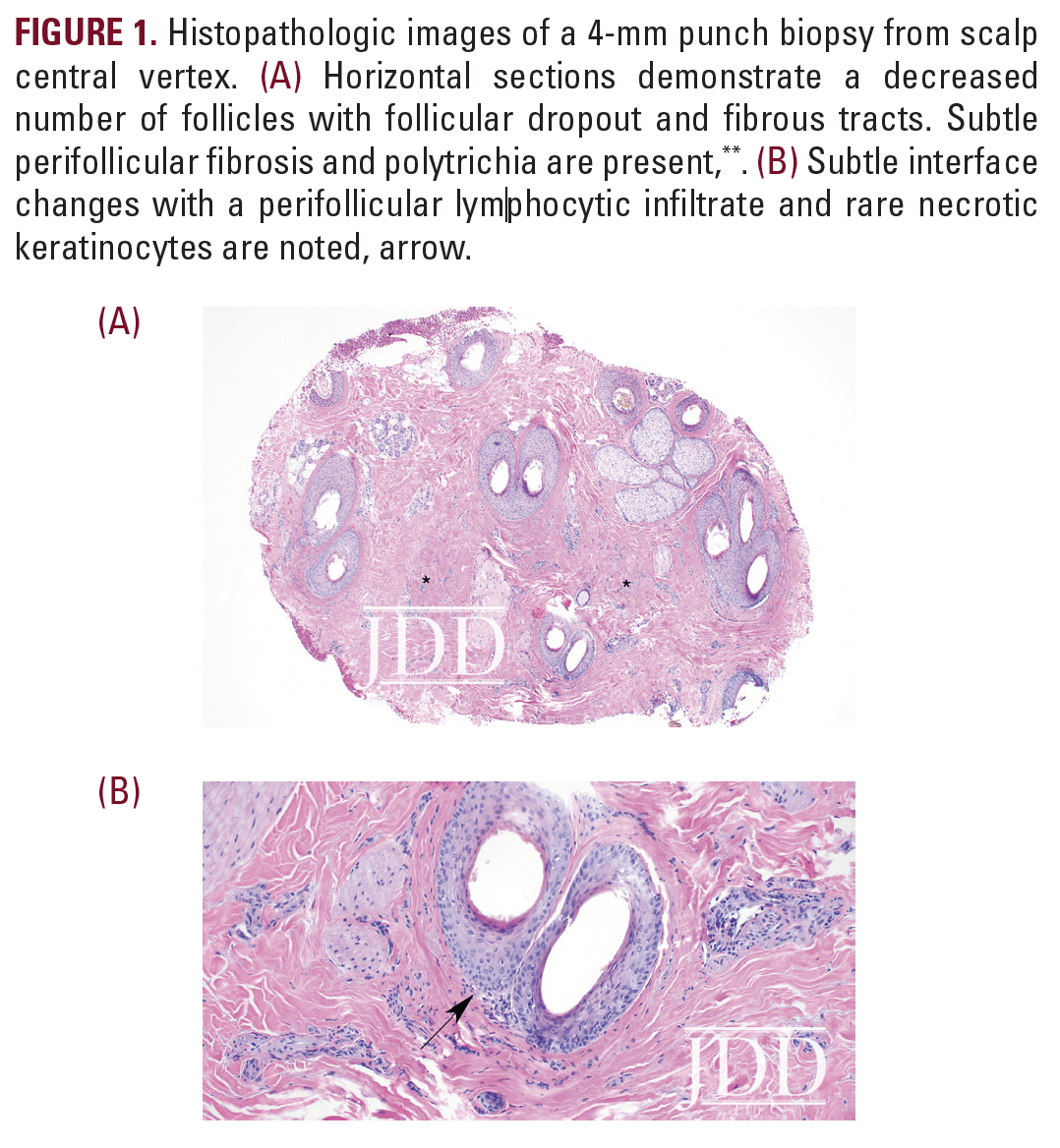

On physical examination, the patient was found to have a small alopecic patch with surrounding scale at the central vertex of the scalp. Trichoscopy revealed perifollicular erythema and hyperkeratosis. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed at the involved site. Histopathologic examination demonstrated follicular dropout characterized by fibrous tracts, diminished number of sebaceous glands, and polytrichia. Sparse lymphocytic inflammation with subtle interface changes within the zones of fibrosis was also noted (Figure 1). A pathologic diagnosis of lichen planopilaris (LPP) was made, confirming clinical suspicion.

At the time of presentation, the patient was taking oral finasteride (5 mg/day). Following the biopsy results, topical clobetasol (0.05% solution twice daily), topical minoxidil (5% foam twice daily), and ketoconazole shampoo (twice weekly) were initiated. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/cc x 2 cc) was administered with plans to repeat corticosteroid injections monthly until signs of active inflammation had resolved.

At the time of presentation, the patient was taking oral finasteride (5 mg/day). Following the biopsy results, topical clobetasol (0.05% solution twice daily), topical minoxidil (5% foam twice daily), and ketoconazole shampoo (twice weekly) were initiated. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/cc x 2 cc) was administered with plans to repeat corticosteroid injections monthly until signs of active inflammation had resolved.

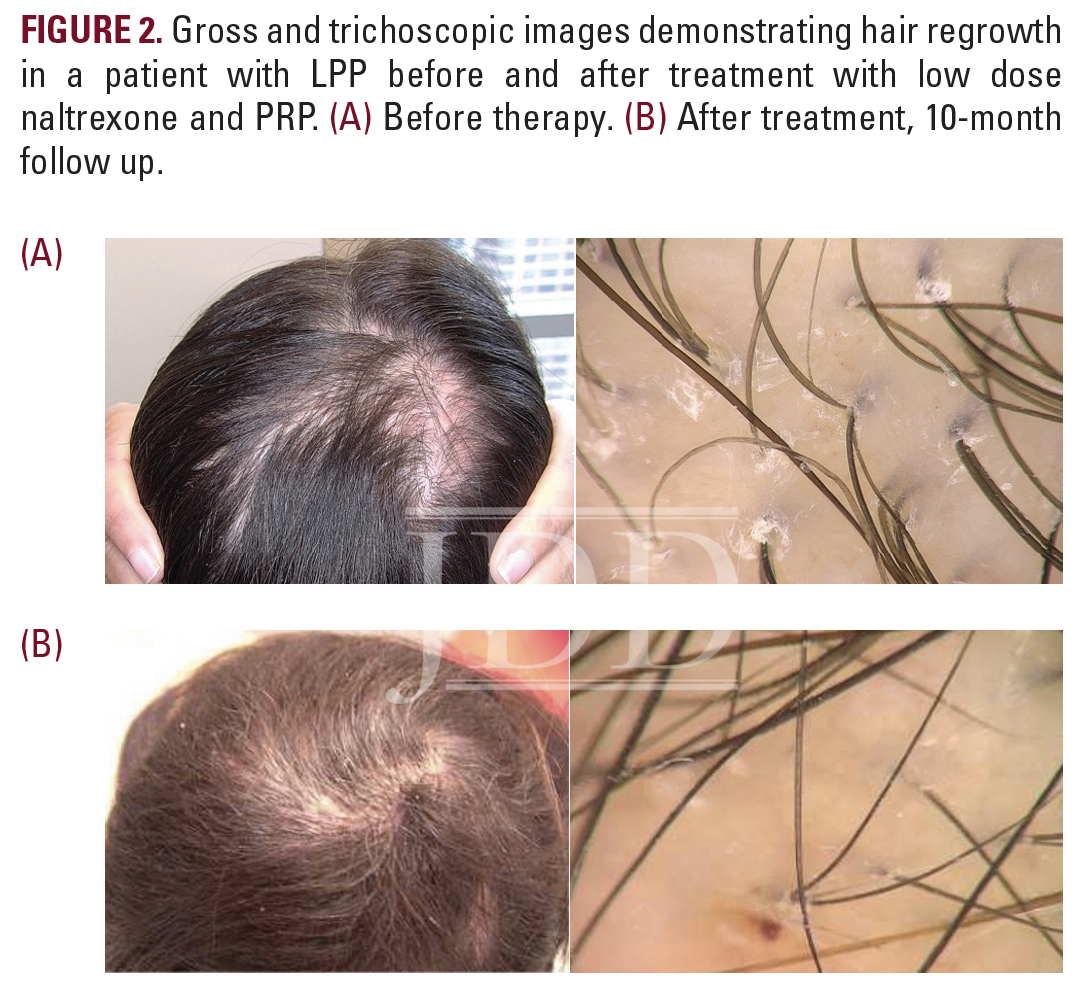

At 1-month, 2-month, and 3-month follow up visits, the patient received corticosteroid injections but was found to have persistent perifollicular scale and possible enlargement of her alopecic patch, suggesting continued disease activity. She was subsequently started on oral doxycycline hyclate at 50 mg twice daily. One month later, despite escalation of therapy, significant progression of disease was observed. The alopecic patch had expanded to 4 x 2 cm (Figure 2a). Given these changes, a decision was made to begin low-dose naltrexone (3 mg/day) and to initiate therapy with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections. An initial treatment of PRP was administered. Whole blood was drawn using RegenKit Blood Cell Therapy and centrifuged for 5 minutes using the Ducker 642VFD-Plus centrifuge (Regen Lab). The patient received a total of 5mL of PRP to the entire scalp, with each injection, containing 0.1 mL PRP, spaced 1 cm apart. Concomitant treatments with PRP injections were planned (sessions every 4-6 weeks for 3 months using 10-12 mL of PRP at each session).

Following 3 months of therapy with low-dose naltrexone and two treatments with PRP, the patient was found to be stable, though not improved. However, 1-month after her third series of PRP injections, she described a global increase in hair density and a reduction in hair shedding. Physical examination confirmed her report, revealing impressive regrowth of hair at the previously scarred, alopecic site (Figure 2b). Therapy with PRP, in addition to the regimen of oral and topical medications previously prescribed, were continued given the patient’s remarkable improvement.

DISCUSSION

Though a cure for LPP does not yet exist, remission may be achievable with anti-inflammatory, immune modulating therapies. Treatment choices are generally guided by patient age, comorbidities, and clinical severity, which is defined by degree of inflammation, rapidity of disease progression, and extent of scalp involvement. According to treatment algorithms, individuals with less than 10% scalp involvement, as was the case with our patient, are typically treated with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and topical tacrolimus, clobetasol, and minoxidil. The use of systemic medications, including hydroxychloroquine, tetracyclines, and 5-α reductase inhibitors may also be considered.2,4

Despite these options, the literature has limited evidence on treatments for this challenging disease. Reports mostly involve small groups of patients and frequently reveal varied or poor clinical response.2 Amongst individuals who do respond to therapy, hair regrowth within alopecic patches is exceedingly rare. Evidence in the literature is limited to several case reports, including a 27-year-old male with regrowth after initiation of oral tofacitinib and dapsone, and a 42-year-old woman with regrowth using low level light therapy.5,6 Due to the lack of large, randomized controlled trials guiding therapeutic management, dermatologists may choose to offer patients well tolerated, alternative treatments including low-dose naltrexone and PRP, as is described in our case report.

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN), a μ-opioid antagonist with antiinflammatory properties, has been successfully utilized in the treatment of patients with LPP, leading to reduced symptoms of pruritus, decreased evidence of scalp inflammation, and slowed disease progression.7 However, a randomized controlled trial published by Lajevardi et al found that while LDN at 3 mg daily improves the severity of LPP, the improvements are not superior to those achieved with topical clobetasol.8 Similarly, literature on the use of PRP as an adjunctive treatment for LPP suggests only mild benefit. In a case study of 10 LPP patients treated with PRP, 3 demonstrated reduced inflammation and decreased hair loss, but none exhibited hair regrowth.9

This case was remarkable given the patient’s dramatic hair regrowth in the setting of cicatricial alopecia. Though our patient was initially treated with traditional therapies, consistent with treatment algorithms proposed in the literature, her clinical response was observed only after the addition of more novel interventions, including low-dose naltrexone and PRP.2 This case highlights the importance of remaining flexible and diligent in therapeutic approaches to LPP and the need for more robust literature regarding prognosis and treatment options for LPP.

DISCLOSURES

REFERENCES

2. Svigos K, Yin L, Fried L, Lo Sicco K, Shapiro J. A Practical Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Classic Lichen Planopilaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(5):681-692. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00630-7

3. Errichetti E, Figini M, Croatto M, Stinco G. Therapeutic management of classic lichen planopilaris: A systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018. doi:10.2147/CCID.S137870

4. Bolduc C, Sperling LC, Shapiro J. Primary cicatricial alopecia: Other lymphocytic primary cicatricial alopecias and neutrophilic and mixed primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(6):1101-1117. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2015.01.056

5. Batra P, Sukhdeo K, Shapiro J. Hair Loss in Lichen Planopilaris and Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: Not Always Irreversible. Ski appendage Disord. 2020;6(2):125-129. doi:10.1159/000505439

6. Randolph MJ, Salhi W Al, Tosti A. Lichen Planopilaris and Low-Level Light Therapy: Four Case Reports and Review of the Literature About Low- Level Light Therapy and Lichenoid Dermatosis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(2):311-319. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00359-x

7. Strazzulla LC, Avila L, Sicco K Lo, Shapiro J. Novel treatment using low-dose naltrexone for lichen planopilaris. J Drugs Dermatology. 2017.

8. Lajevardi V, Salarvand F, Ghiasi M, Nasimi M, Taraz M. The efficacy and safety of oral low dose naltrexone versus placebo in the patients with lichen planopilaris: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1774488

9. Svigos K, Yin L, Shaw K, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma in lichen planopilaris and its variants: A retrospective case series demonstrating treatment tolerability without koebnerization. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1506- 1509. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.026

SOURCE