In a previous article, Dr. Neal Bhatia shared his views and advice on the many options available to dermatology residents after residency training. In this article, he offers further advice to residents on finding their first job, including a primer on understanding employment contracts.

Marketing as a Job Candidate

The successful job applicant plans ahead and is strategic. The phrase “knowledge is power” cannot be overstated in the process of finding the right job in medicine. Whether you are searching for a job in a single-specialty group, multi-specialty group, Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) or managed care setting, or academic department, there are some pivotal answers to have in place for the inevitable questions and deliberations.

Know Your Worth

Aside from the comparisons based on compensation, the dermatologist has value in the marketplace for the skills that are brought to the clinic setting. Training and expertise in medical dermatology, surgery, and aesthetic procedures are valuable commodities and cannot be undervalued. However, not all practices will need the services that you offer, so it is imperative to know the market well and specifically to know the office dynamics. Although there is no crystal ball revealing exactly how the new dermatologist will fit in, you can predict whether the current practice will benefit from the addition of your abilities or whether it will lead to competition with the established partners and a possible backlash. For example, a clinic that has long had a need for a dermatologist based on referral patterns, with a part-time dermatologist in place, or with a recent vacancy, might be a perfect fit for a dermatologist with diverse interests but a primary focus on medical dermatology issues. In contrast, a group practice of dermatologists that already has an established Mohs surgeon may not need another one unless there are overwhelming schedule needs, in which case these will need to be discussed prior to initiating employment so that competition for patients and potential resentment do not impact office dynamics. Therefore, a young ambitious Mohs surgeon might search elsewhere to establish a niche, unless the search criteria for a job include a mentor or perhaps sharing a patient load. In addition, any expectations of having to participate in medical dermatology, as well as see hospital consultations, should also be discussed up front. The dermatologist who has traditionally read his or her own pathology slides might also want to avoid a job setting where the biopsy specimens are sent to a dermatopathologist in the group, or, in the case of a hospital-based group, perhaps even to a general pathologist. Finally, if the overall market for cosmetic surgery is low, or the focus of the clinic is primarily on the care of the elderly or indigent, you can expect a small return on the need for a procedural dermatologist.

Aside from the salary information and benefits, there are many important screening questions that cannot be overlooked. It is important not to fall into the trap of considering only the salary and location of the position without also considering some of the intangibles. Several important questions to ask prior to moving further down the path are:

• How long has the position been offered?

• Do the skills in demand match my skills?

• What are the expectations for the path to partnership or further involvement in the office down the road?

Understanding Contracts

It is easier to promote the application when the physician is well qualified for the position such that the employer sees the impact of finalizing the contract. Elaborating on and highlighting your strengths will accentuate your presentation and convey your interest level. However, it is critical to be realistic, keep demands legitimate, and define limits. These can be shared in an interview, but it is otherwise important to keep them private. Moreover, although many experts stand by pearls such as “Don’t be afraid to ask for more,” remember that some things may not be negotiable. Aside from the listed offer that is being considered, the applicant has to reflect on some important issues to do with taking the next step and pursuing the offer. Setting priorities on what is needed, what is wanted, and what “you can get” are essential before entering any negotiations.

Important strategies for negotiations must be made before the contract is drawn up because once the process starts there are more challenges involved with alterations. However, the details of the contract will differ depending upon the employer, the employment setting, and the demand for the position. In addition, if the chemistry between the parties is stable and there is a perceived fit for the position, the standard contract can be changed by negotiating in steps rather than with broader demands.

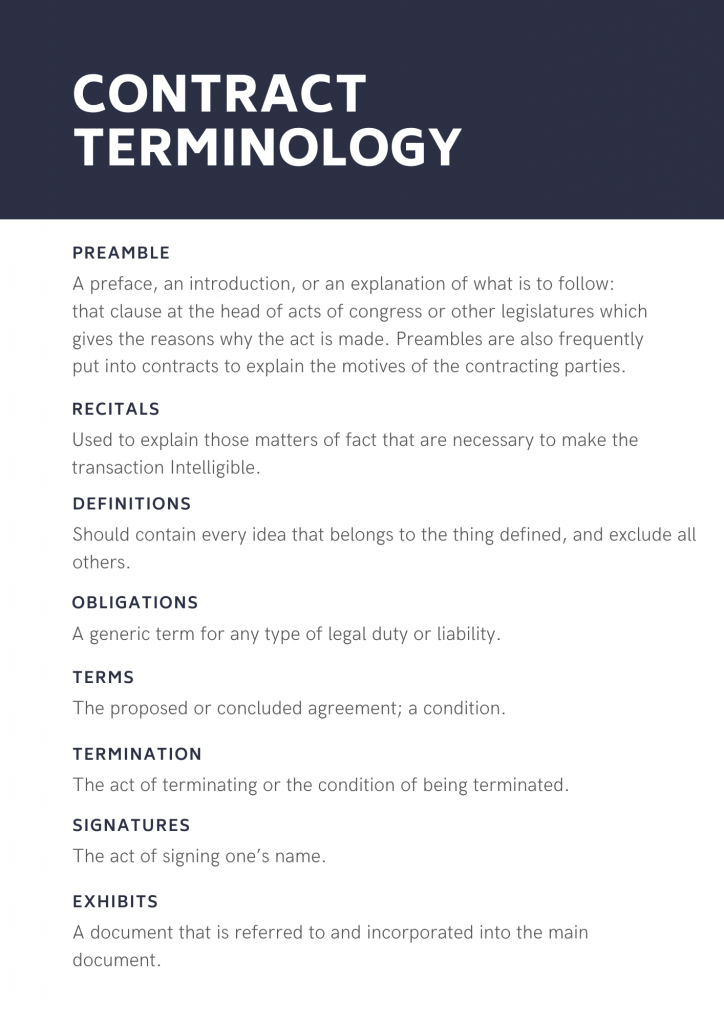

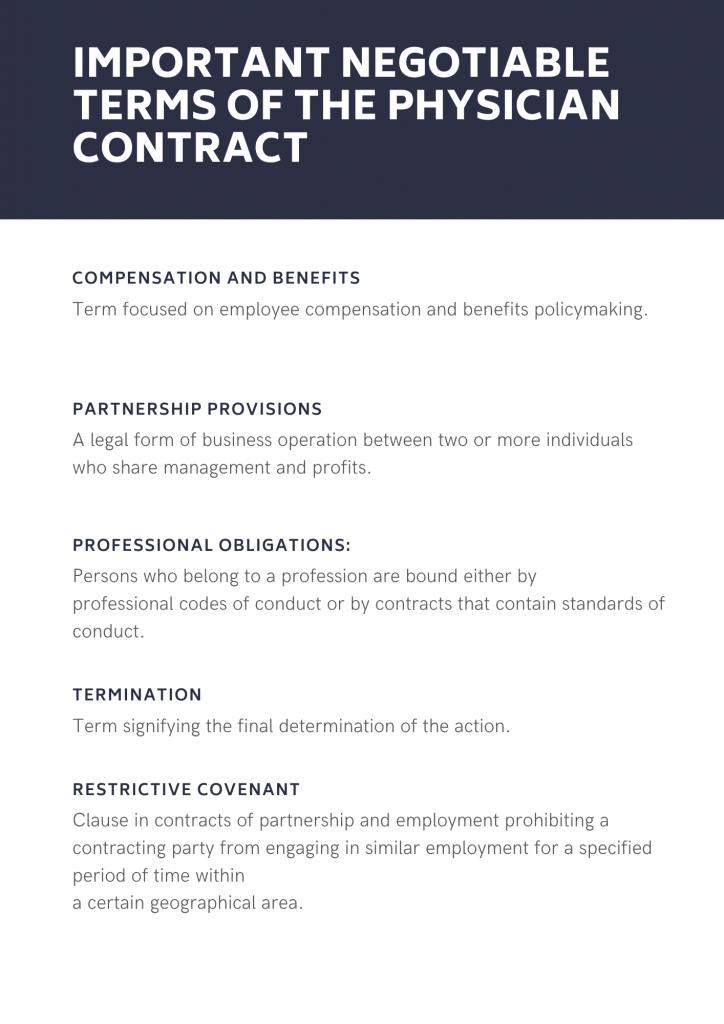

The physician applicant needs to become familiar with the layout and structure of the standard contract (see Table 1), as well as with how the negotiable terms between the parties are integrated into the contract (see Table 2).

Table 1

Table 2

The advice of many professional experts in physician contract law point out one common fatal flaw that results in physicians ending up dissatisfied with contract terms: they didn’t read the contract closely beyond learning how much they would earn. You should be aware of the other terms aside from the obvious compensation, benefits and other primary issues such as vacation and job description. However, there should also be a healthy balance between the extremes of not thoroughly reading the contract and hiring a lawyer to dissect the details of each section in the contract. The spirit of the contract is to allow for a successful beginning of employment, but at the same time it protects the interests of both parties during employment and allows for ease of separation when employment ends.

Negotiations Begin With the Offer Letter

Before you ever receive an employment contract to review, the potential employer usually sends an offer letter that outlines the position and connects the employer and physician in line with the employer’s standard contract. Physicians continue to move away from independent practice and toward employment in hospitals or other large organizations. Although this switch frees physicians from the burdens of running a business, it is critical for you to understand your rights and responsibilities before agreeing to an employment contract.

Termination and Coterminous Clauses

Most contracts allow an employer to terminate an agreement with or without cause, commonly after the first 90 days. While these arrangements are not uncommon, you should recognize that a “five-year contract” that allows termination without cause after a shorter amount of time effectively reduces the contract length to that shorter time period. Also, you should be fully aware whether the termination of an employment agreement also terminates privileges at the hospital. Termination can be subjective, which is an important intangible in the employment contract process. You need to be completely aware of the definitions and standards in that policy to avoid potential abuse by a supervisor who really wants to terminate employment because they “don’t like” you, rather than because of any wrong-doing or lack of merit.

This also includes code of conduct and conflict of interest policies that might be in place. If the hospital or healthcare institution mandates policies that all employees are expected to follow, you should request to review these documents before signing your contract, and you might benefit from consulting with other physicians who are currently employed. One pitfall to watch out for is an overly broad definition of unacceptable physician behavior, especially when it comes to conflict of interest. Awareness of the regulations of the contract is essential to prevent you unintentionally violating the contract by becoming involved in activities that your new employer perceives as either competitive or distracting.

Restrictive Covenants

While healthcare non-compete agreements are illegal in many states, physicians who are subject to them need to recognize what they are agreeing to. For instance, while agreeing not to practice within a 15-mile radius of the employer for a two-year period might not seem like a lot during the honeymoon period after the contract is signed, the ramifications are often far larger than physicians anticipate when such provisions are enforced.

Did you enjoy this post? Find more on Navigating Your Career here.

Next Steps in Derm is brought to you by SanovaWorks.