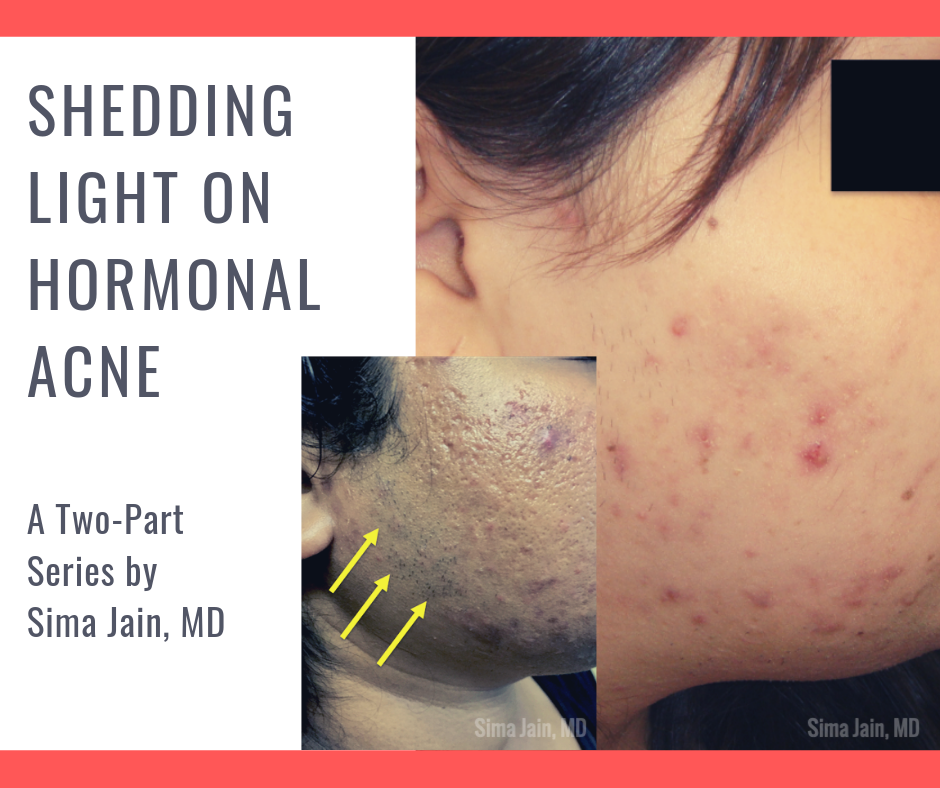

Acne is the most common disease of the skin and may be an important clue of an underlying types endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), Cushing syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) or an androgen-secreting tumor (see Fig 1).

As board certified dermatologists, we should be able to distinguish which patients presenting with types of acne may need further evaluation for a possible underlying endocrinopathy. In this two-part series, we will be focusing on hormonal acne specifically related to PCOS, including the exam, work up, diagnosis, treatment and long-term implications of this syndrome.

PCOS is a complex disorder affecting 5-10% of reproductive-age women and is characterized by a state of hyperandrogenism and often hyperinsulinemia. It is the most common endocrine disorder in women and is a major cause of infertility due to lack of ovulation. Patients can present with a wide range of symptoms, which may make the precise diagnosis difficult.

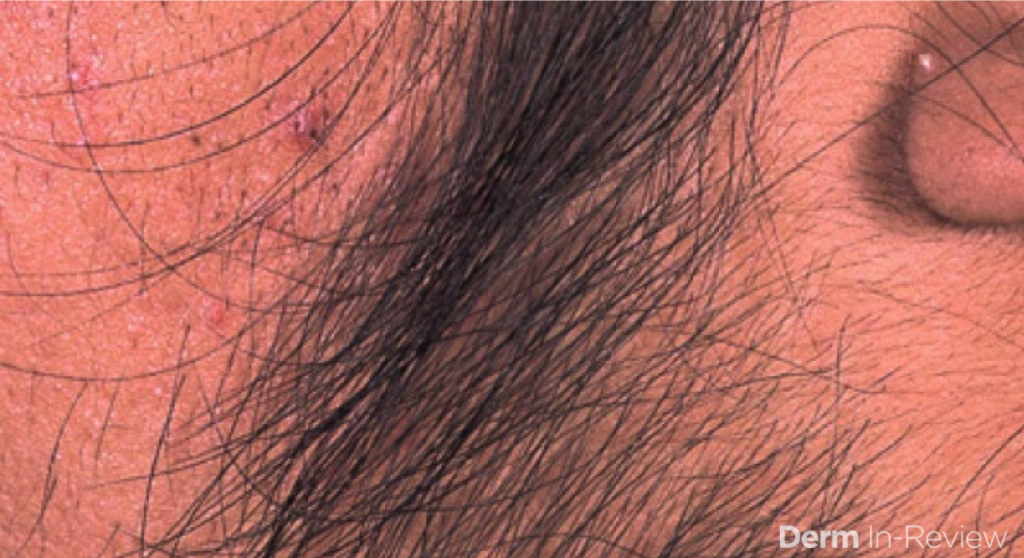

Acne is a common skin manifestation but other potential findings may include hirsutism (increased terminal hairs in a male-pattern distribution, see Fig 2), scalp alopecia (see Fig 3), acanthosis nigricans and less frequently seborrheic dermatitis. Non-dermatologic symptoms and signs may include irregular menses (oligomenorrhea), hormone fluctuations, insulin resistance, polycystic ovaries and infertility.

Women with PCOS have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes and other metabolic complications. Furthermore, during childbearing years women have an increased risk of miscarriage, gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Thus, early diagnosis is important since there are many long-term consequences associated with this syndrome.

The underlying etiology of PCOS is not completely understood but it is likely multifactorial and due to a combination of genetic, endocrine and environmental factors. Growing data suggests a key component in the pathogenesis is a defect in the insulin pathway resulting in insulin resistance. The compensatory hyperinsulinemia is thought to promote a state of hyperandrogenism that is characteristically seen in this syndrome. Although PCOS was often considered a disease of obesity in the past, it is now known that patients with a normal or low body mass index (BMI) can also have this syndrome.

The diagnosis of PCOS is currently based on criteria from the 2003 European Society for Human Reproduction and American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ESRHE/ASRM) Rotterdam consensus meeting, which expanded the previous classification. At least two out of the following three criteria are required for diagnosis:

- Oligo-anovulation

- Hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical)

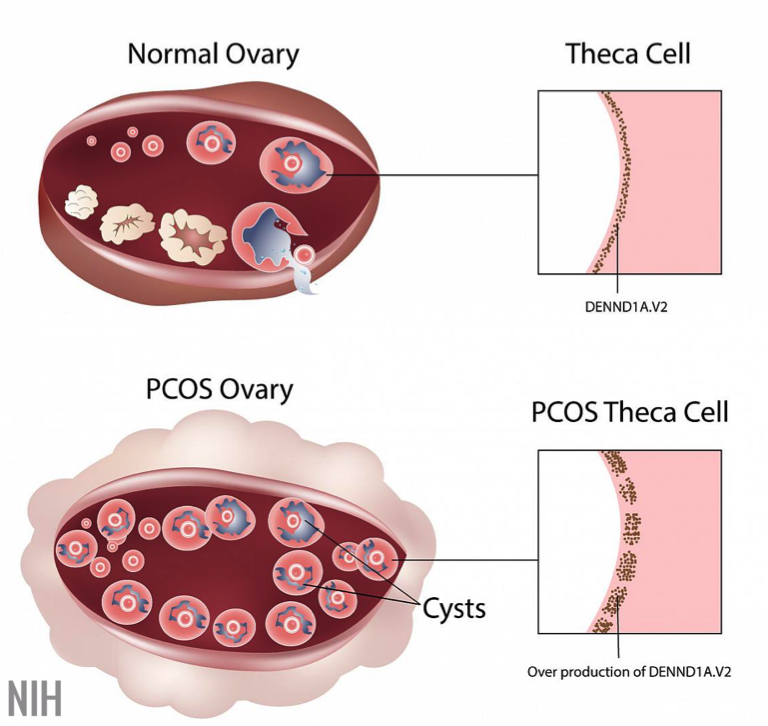

- Polycystic ovaries by ultrasound (checking number of antral follicles and ovarian volume, [see Fig 4])

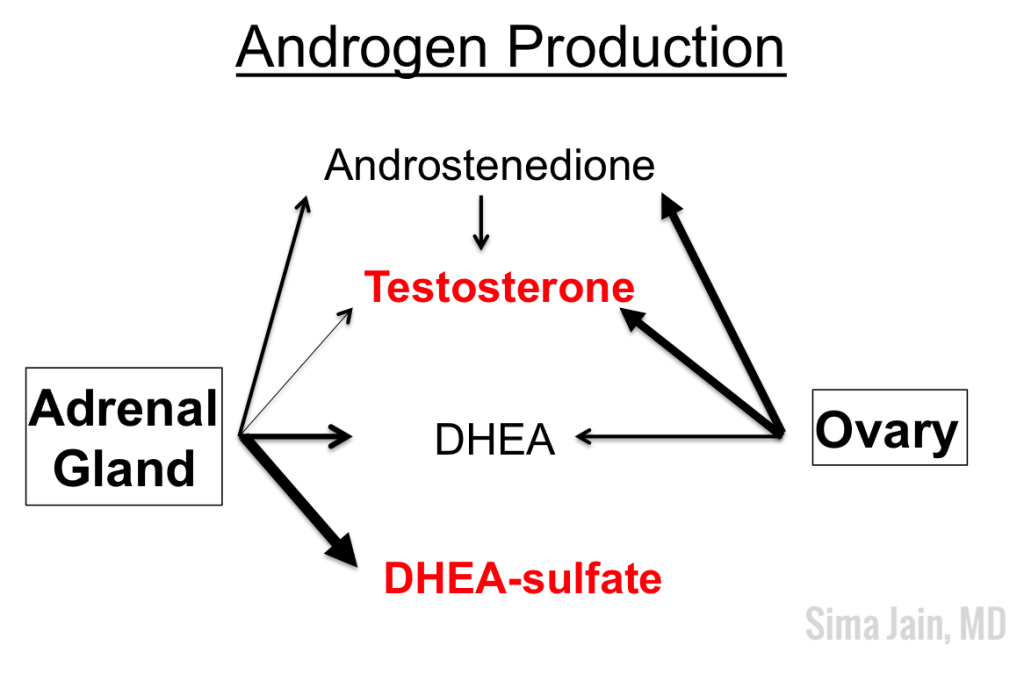

The first criterion of oligo-anovulation describes irregular menses with lack of proper ovulation. It is not abnormal for women of childbearing age to have some variation in menstruation (21-35 days), but if the patient regularly goes beyond 35 days without menstruating, it is considered oligomenorrhea. Amenhorrhea (complete absence of menstrual periods) may also be seen. Hyperandrogenism, the second diagnostic feature, can be seen clinically (acne or hirsutism on exam) or biochemically (laboratory studies showing elevated testosterone or dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA], see Fig 5). The third criterion is related to the chronic state of anovulation often seen in PCOS patients. Since no egg matures or is released due to the abnormal hormonal milieu, ovulation does not occur and the follicles accumulate in the ovaries. The increased number of small cysts have a polycystic appearance with a characteristic ‘string of pearls’ appearance on ultrasound of the ovaries.

Since a dermatologist may be the first or only physician a young female patient with hormonal acne sees, it is imperative for us to be aware of the clinical clues that suggest hyperandrogenism. First, it is important to inquire if the patient’s menstrual cycles are regular to screen for oligomenorrhea and potential anovulation. Be mindful if the patient is on an oral contraceptive pill, as this can mask underlying oligomenorrhea since the external hormones are essentially regulating the menstrual cycle. In addition to discussing the menstrual history, it is important to inquire about potential hirsutism by asking if the patient has noticed increased hair growth to the face (sideburn area, chin, upper cutaneous lip), chest, abdomen and/or inner thighs. Many patients do not realize that increased hair growth may be related to acne and often feel embarrassed to bring it up on their own. A third important feature to be aware of is hair loss to the scalp. It is not uncommon for patients to say they have noticed thinning of their hair or increased shedding, especially to the front of their scalp.

When examining the patient, the distribution of hormonal acne is important as it often involves the lower half of the face, especially along the jawline. Other suggestive features include the presence of terminal hairs with a male pattern distribution (see Fig 6), scalp hair loss with retention of the frontal hairline and excess weight. The pattern of hair loss is consistent with androgenetic alopecia (also known as female pattern hair loss) and there is often decreased hair volume with a noticeable widening of the midline part of the scalp (see Fig 7). Often, a significant variation in hair shaft diameter is seen on dermoscopic exam with this type of hair loss. Lastly, if the patient is overweight, it is not uncommon to see the presence of velvety hyperpigmentation on the lateral neck and axillae consistent with acanthosis nigricans (see Fig 8) due to a state of hyperinsulinemia.

If the evaluation points toward hyperandrogenism, laboratory evaluation and ultrasound imaging may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis. The second part of this series will focus on the remaining work up for PCOS and the different treatment options for hormonal acne.

Photo Credits:

Figures 1, 3, 5-8 Courtesy of Sima Jain, MD

Figure 2 Courtesy of Derm In-Review

Figure 4 Courtesy of NIH

Did you enjoy this post? Find more on Medical Derm topics here.