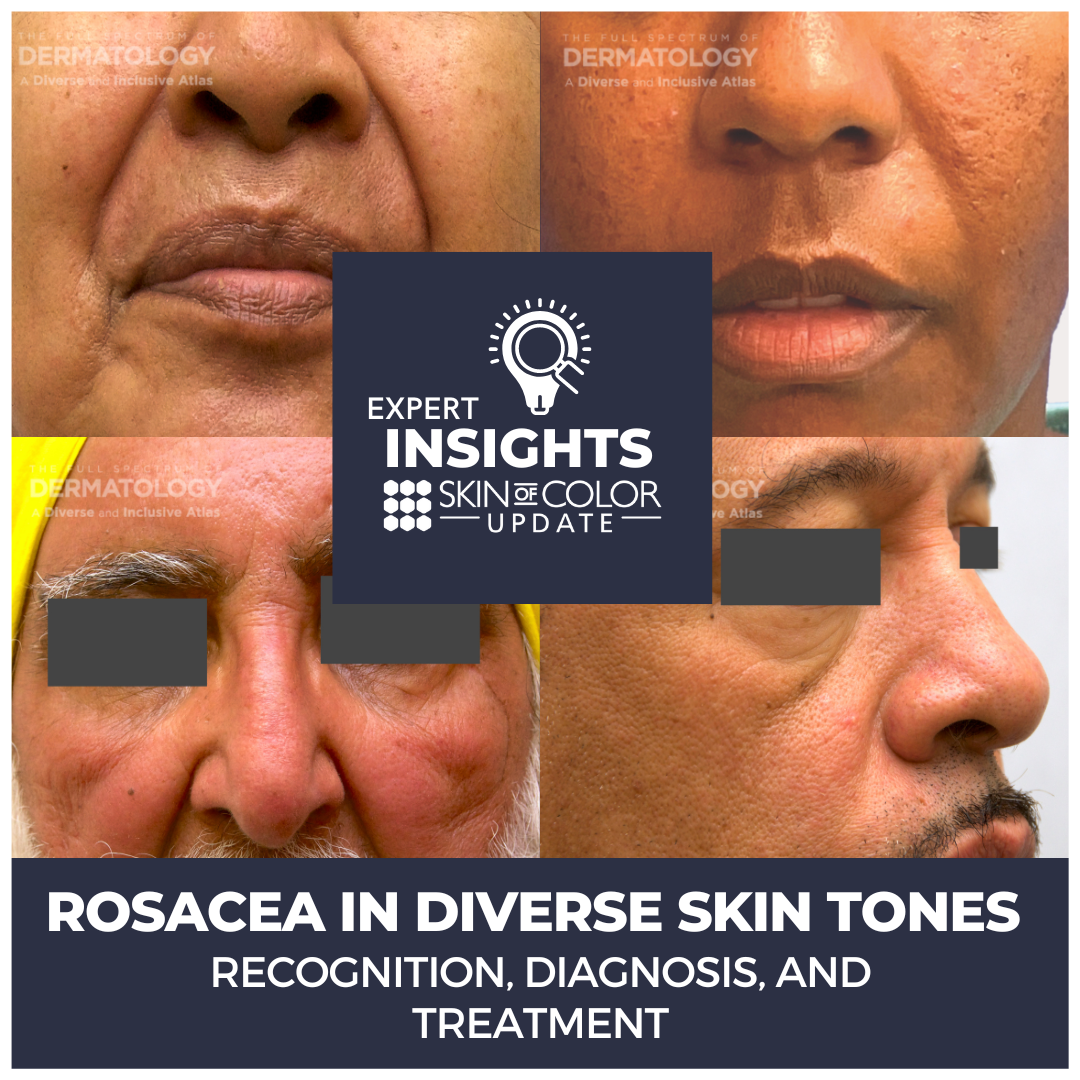

We have probably all seen a patient with rosacea. After all, it is quite common in middle-aged, fair-skinned women. Here, however, we will explore a talk given by Dr. Hilary Baldwin (Medical director of the Acne Treatment & Research Center in Morristown, NJ and Brooklyn, NY, and Clinical Associate Professor of Dermatology at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical Center) at the 2022 Skin of Color Update Conference on rosacea in diverse skin tones.

Rosacea Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

Dr. Baldwin was one of multiple authors that published this review of rosacea in skin of color (SOC)[1]. The authors highlighted that rosacea is not uncommon in darker skin. A survey of United States National Ambulatory Medical Care showed that about 8% of rosacea patients were black, Pacific Islander, Hispanic, or Latino [2]. The global prevalence is as high as 40 million, primarily in countries in Africa, Asia, and South America [3-5]

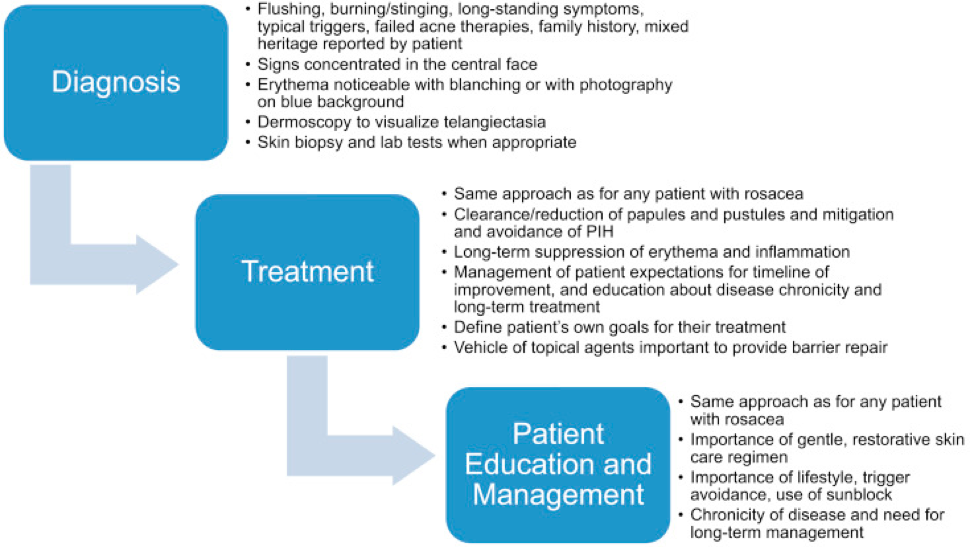

Clinical signs of rosacea include erythema, telangiectasias, papules and pustules, phymatous changes (less common in SOC), and rare postinflammatory changes [2]. Erythema, flushing and telangiectasias may be difficult to recognize in more richly pigmented skin. It may be easier to elicit symptoms to establish the diagnosis. Symptoms may include stinging, burning, and pruritus (most common). An episodic sensation of warmth and sensitivity to skin products and gritty, sensitive eyes with rheum has also been reported. 72% of people report worsening of symptoms with sun exposure [2]. Given this diverse presentation, it is no surprise that many patients have a misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis, which can lead to decreased quality of life and more advanced disease.

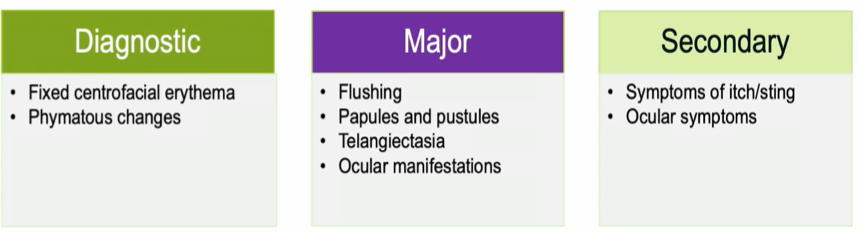

Updates in Consensus for Diagnosis

Previously, rosacea was classified by subtypes, including ocular, granulomatous, erythematotelangiectatic, and papulopustular. However, multiple consensus groups have recommended the transition to phenotypic descriptions [3, 7-9], as illustrated below:

Yet for patients with darker skin tones where erythema is more difficult to appreciate, phenotypic description may become a challenge, leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis.

Treatment of Rosacea in Skin of Color

The first step to treatment for rosacea in SOC, notes Dr. Baldwin, is listening to the patient’s symptoms and creating a patient-centered plan while managing expectations. Focus on what the patient cares about, which may be redness only or papules only, because treatment may be long-term and expensive. Treatment for rosacea patients of all skin tones is essentially identical. However, as with acne therapy, clinicians must be careful not to cause cutaneous irritation and resultant drug-induced hyperpigmentation. For topical therapy, the best tolerability data can be seen with ivermectin 1% cream, minocycline 1.5% foam, and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide 5%. Another option, of course is to bypass the skin altogether and treat with anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline.

Topical Treatments for Rosacea

Ivermectin 1% cream was shown to be highly effective and to have a superior tolerability profile to both azelaic acid 15% gel and metronidazole 0.75% Cream [10].

Minocycline 1.5% foam is a well-established molecule with multiple mechanisms of anti-inflammation [11]. It has low global rates of resistance [12] and is effective orally in rosacea. However, rare systemic adverse events can be significant [13]. In the pivotal phase 3 trials, 1.5% minocycline foam was shown to produce rapid and significant reduction in inflammatory lesion count with virtually no cutaneous adverse effects [14].

Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) has been shown to be an effective drug for treating the papules and pustules of rosacea; however, its use has been limited by concentration-dependent irritation [15-17]. This is especially true in rosacea patients who often complain of skin irritation at baseline. In a new formulation, benzoyl peroxide 5% has been microencapsulated in a silica shell that reduces the speed with which the benzoyl peroxide is released onto the surface of the skin. In the phase 3 pivotal trials, this resulted in early and significant reduction in mean inflammatory lesion count and high success rate with good tolerability. [18-19].

Oral Treatments for Rosacea

40 mg modified release doxycycline is the only oral medication that is FDA-approved for the treatment of rosacea. The unique formulation utilizing 30 mg immediate release and 10 mg delayed release beads provides anti-inflammatory activity without exceeding the antibiotic threshold. Safety and the absence of antibiotic resistance was noted in a 9-month safety study. During the phase 3 pivotal trials, 40 mg modified-release doxycycline was shown to be effective and well-tolerated [20].

Sarecycline, a tetracycline FDA approved for acne, has been studied in a 12-week placebo-controlled pilot study in patients with moderate-severe rosacea. Sarecycline has been shown to have a narrow spectrum of antibiotic activity. It has been shown to have 16- to 32-fold less activity against gram-negative gut flora than minocycline and doxycycline and to have a low incidence of spontaneous mutation. [21-23]. Its use was found to produce statistically significant improvement in the Investigator’s Global Assessment, reduction of inflammatory lesions, and reduction in burn, erythema, and pruritus without serious adverse events [24].

Skin Care Regimens for Rosacea

Rosacea is fundamentally a barrier deficient disorder. In addition to pharmacologic therapy, the best rosacea regimen includes good quality skin care [25]:

-

- Gentle, non-alkaline, fragrance-free emollient cleanser once per day in the evening

- Quality moisturizers that contain emollients, humectants, ceramides and other barrier-repair lipids, have a low pH, and are fragrance-free.

- Light, water-based cosmetics that do not require excessive cleansing to remove

- Physical sunblock (e.g., zinc oxide)

Summary and Takeaways

As we have highlighted, rosacea is a challenging disease to diagnose, treat, and educate patients with any skin tone. This is especially true in patients with more richly-pigmented skin who have historically been ignored with this diagnosis. It is recommended that clinicians keep a high index of suspicion and perform a thorough history and careful examination. This allows us to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, reduce progression of the disease, and treat with well-tolerated, evidence-based therapies. We leave you with this final diagram from a figure from one of Dr. Baldwin’s group’s papers that highlights the diagnosis, treatment, and education strategies to keep in mind. So, go forth and treat that common rosacea in all populations!

References

-

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, Desai SR, Rendon MI, Taylor SC. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: Review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, Feldman SR. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(10):13030/qt1mv9r0ss. Published 2014 Oct 15.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 Suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Cribier B. Rosacée : nouveautés pour une meilleure prise en charge [Rosacea: New data for better care]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017;144(8-9):508-517.

- Dlova NC, Mosam A. Rosacea in black South Africans with skin phototypes V and VI. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(6):670-673.

- Rueda LJ, Motta A, Pabón JG, et al. Epidemiology of rosacea in Colombia. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(5):510-513.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: The 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):148-155.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92(5):234-240.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):65-79.

- Stein Gold L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Long-term safety of ivermectin 1% cream vs azelaic acid 15% gel in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: results of two 40-week controlled, investigator-blinded trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(11):1380-1386.

- Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2):258-265.

- Sardana K, Gupta T, Garg VK, Ghunawat S. Antibiotic resistance to Propionobacterium acnes: worldwide scenario, diagnosis and management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(7):883-896.

- Wang L, Li XH, Wen X, et al. Retrospective analysis of 19 papulopustular rosacea cases treated with oral minocycline and supramolecular salicylic acid 30% chemical peels. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(2):1048-1052.

- Gold LS, Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, et al. Minocycline 1.5% foam for the topical treatment of moderate to severe papulopustular rosacea: Results of 2 phase 3, randomized, clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1166-1173.

- Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: I. Etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(3):327-344.

- Del Rosso JQ. The use of moisturizers as an integral component of topical therapy for rosacea: clinical results based on the Assessment of Skin Characteristics Study. Cutis. 2009;84(2):72-76.

- Lonne-Rahm SB, Fischer T, Berg M. Stinging and rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79(6):460-461.

- Raeesi M, Mirabedini SM, Farnood RR. Preparation of Microcapsules Containing Benzoyl Peroxide Initiator with Gelatin-Gum Arabic/Polyurea-Formaldehyde Shell and Evaluating Their Storage Stability. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(24):20818-20825.

- van Zuuren EJ, Arents BWM, van der Linden MMD, Vermeulen S, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J. Rosacea: New Concepts in Classification and Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):457-465.

- Fowler JF Jr. Combined effect of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline (40-mg doxycycline, usp monohydrate controlled-release capsules) and metronidazole topical gel 1% in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(6):641-645.

- Moore AY, Charles JEM, Moore S. Sarecycline: a narrow spectrum tetracycline for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris. Future Microbiol. 2019;14(14):1235-1242.

- Zhanel G, Critchley I, Lin LY, Alvandi N. Microbiological Profile of Sarecycline, a Novel Targeted Spectrum Tetracycline for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;63(1):e01297-18. Published 2018 Dec 21.

- Bikowski JB. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline for acne and rosacea. Skinmed. 2003;2(4):234-245.

- Rosso JQ, Draelos ZD, Effron C, Kircik LH. Oral Sarecycline for Treatment of Papulopustular Rosacea: Results of a Pilot Study of Effectiveness and Safety. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(4):426-431.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, Desai SR, Rendon MI, Taylor SC. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: Review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1722-1729.e7.

This information was presented by Dr. Hilary Baldwin at the 2022 Skin of Color Update conference held on September 9-11-2022. The above highlights from her lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Nishad Sathe.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on skin of color dermatology here.