To kick off ODAC 2021, Dr. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, tackled two clinical dilemmas that are frequently seen among pediatric patients in the dermatology office: poorly controlled atopic dermatitis and infantile hemangiomas. Dr. Kirkorian reviewed currently available systemic therapies for atopic dermatitis as well those in the drug development pipeline. She went into detail about how she utilizes her preferred systemic agent, cyclosporine, to stabilize severely affected patients, how she mitigates potential adverse events with lab monitoring and counseling, and how she transitions to safe, long term therapy. Dr. Kirkorian also reviewed diverse vascular anomalies among pediatric patients, identifying risk factors that indicate the need for intervention or further medical workup for infantile hemangiomas and teasing out mimickers. Let’s dive in!

The nitty-gritty for systemic therapy in pediatric atopic dermatitis

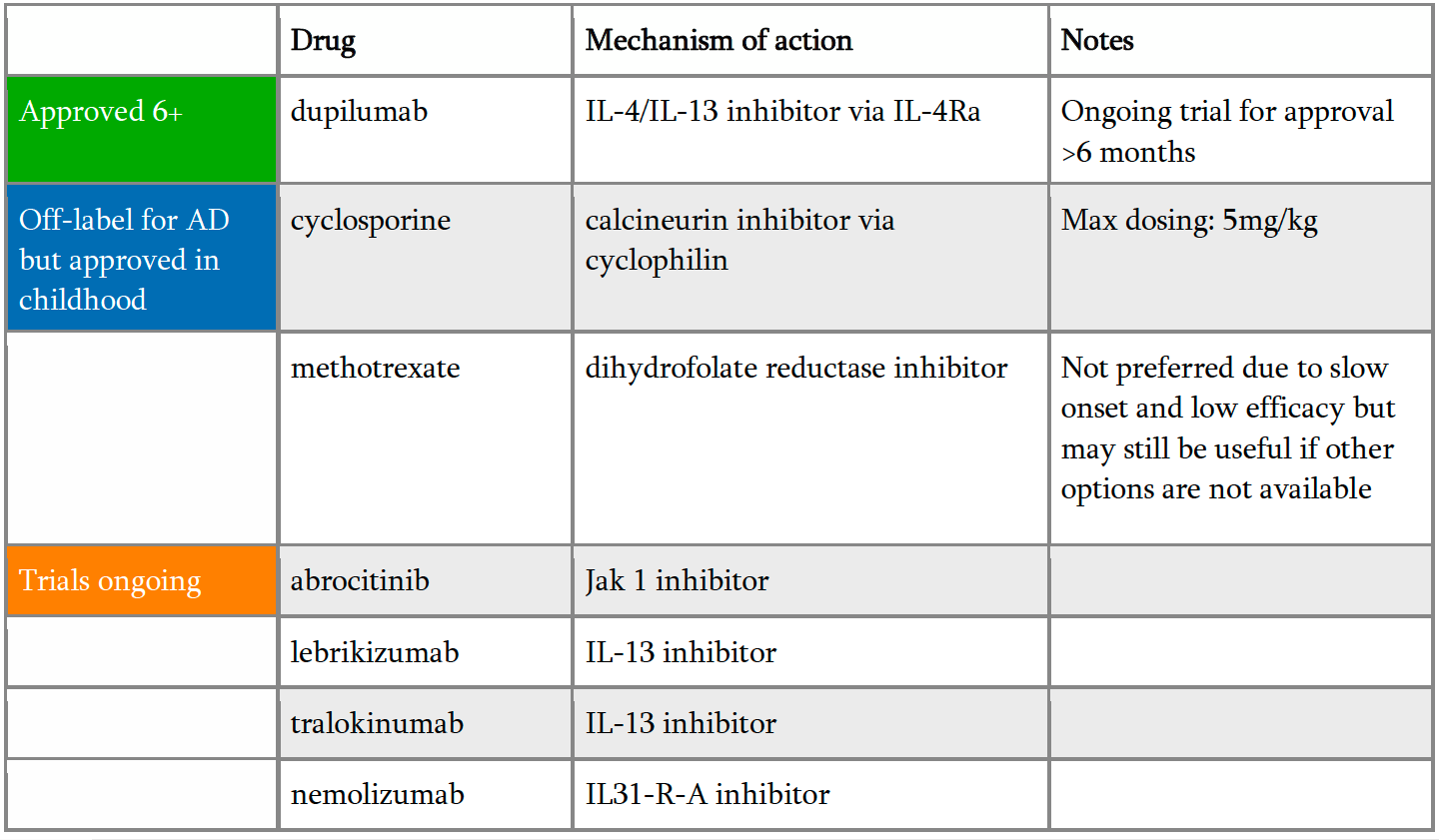

When topical therapy just doesn’t cut it, Dr. Kirkorian encourages providers to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with systemic medications. She stressed these children are frequently in crisis due to impaired sleep and disrupted learning; thus, a therapy that works fast and works well is essential. For Dr. Kirkorian, these are cyclosporine and dupilumab. While there are currently limited options for approved systemic medications, several new classes of biologics are currently in trials (Table 1).

Dupilumab has revolutionized treatment of atopic dermatitis and is currently approved for children over the age of 6 for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. However, it is frequently not so straight forward to get insurance coverage for this expensive injectable medication. Dr. Kirkorian outlined her strategy to get her patients better fast and transition them to safe, long term therapy:

-

- Document the investigator global assessment (IGA) or EASI score and failure of topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitor, and/or topical crisaborole.

- If possible, get dupilumab approved without step therapy insurance permitting.

- If insurance requires step therapy, initiate cyclosporine therapy for three months:

- Modified cyclosporine 5mg/kg (split into twice-daily dosing)

- Baseline vitals (blood pressure) and labs: CBC, CMP, lipids

- Repeat labs and blood pressure monthly for three months

- Handout provided to patient with adverse effects, drug interactions, statement about off-label usage. She recommends this be signed and uploaded to the EMR.

- After three months of cyclosporine, document improvement with therapy, state the contraindication to long term use and initiate the prior authorization for dupilumab therapy.

- Once on dupilumab therapy, start tapering cyclosporine by 50% every 2 weeks so the patient is off cyclosporine eight weeks into dupilumab therapy when it has reached 90% efficacy.

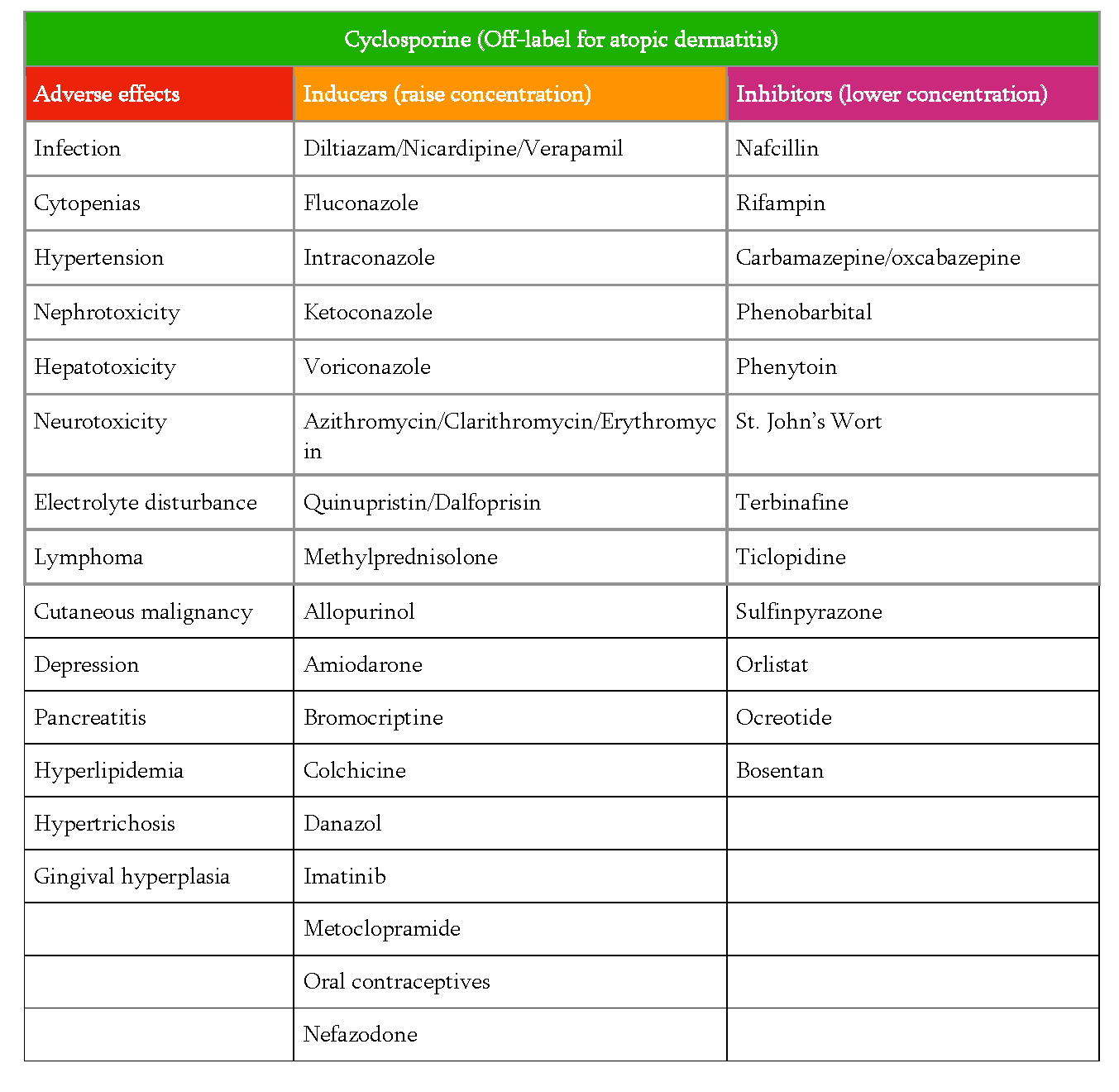

While Dr. Kirkorian considers cyclosporine safe for short term therapy, she stressed the importance of counseling to make sure the parents are aware of potential adverse effects and also agree to partner in the monthly lab monitoring. She recommended providing parents with a printed list of potential side effects (Table 2), reviewing them and then having the nurse review them a second time to make sure they have had sufficient time to understand and ask questions. Dr. Kirkorian also provides information in writing regarding medications that can affect the concentration of cyclosporine as well as counseling regarding avoiding live vaccinations while on treatment. The live vaccine schedule includes rotavirus (given at 2, 4, and 6 months old), varicella (given at 12-15 months with booster at 4 years), and MMR (given at 12-15 months with booster at 4 years). Patients with reproductive potential during cyclosporine therapy need counseling regarding risks of cyclosporine in pregnancy.

What about methotrexate? Dr. Kirkorian explained methotrexate is not her preferred therapy for pediatric patients for several reasons. Methotrexate onset is slow. Also, it is not as effective as cyclosporine to control atopic dermatitis. Lastly, the weekly dosing schedule increases the risk of dosing errors. Dr. Kirkorian advises if you are going to use methotrexate in a patient, provide a dosing calendar and have the parents sign it. She noted that methotrexate is still a very useful drug for many other dermatologist diseases in childhood and as an adjunctive treatment for atopic dermatitis (e.g. with dupilumab failure or waning efficacy).

When to worry: Vascular birthmarks in babies

When evaluating an infant with a vascular birthmark, how do you know if it is an infantile hemangioma? Dr. Kirkorian advised newborn photos can be very helpful. In the whirlwind of a new baby, it can be hard for parents to recall if the spot was present at birth or became noticeable shortly after birth. This is where photos from the first days of life can be very helpful. As opposed to congenital vascular tumors, infantile hemangiomas are very subtle, if at all present, at birth and then develop quickly in the first month of life with a “fire engine” red color and irregular borders. This is in stark contrast to congenital hemangiomas and port wine stains, which are fully formed vascular anomalies at the time of birth.

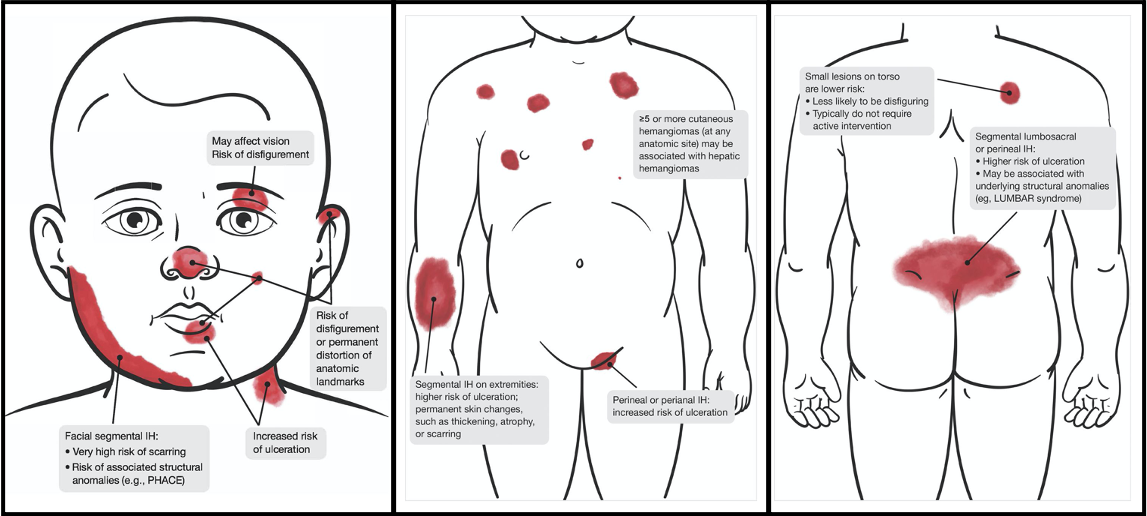

Why is this distinction so critical? Dr. Kirkorian reminded the location of infantile hemangiomas can be associated with developmental syndromes and also dictates prognosis and treatment options. Segmental infantile hemangiomas on the face could indicate PHACE(S) syndrome, which stands for posterior fossa malformation, hemangioma, arterial lesions, cardiac and aorta abnormalities, eye defects, and sternal cleft and/or supraumbilical raphe. Infants with suspected PHACE syndrome should undergo an echocardiogram, MRI/MRA of the brain with extension to the aortic arch, and ophthalmologic referral. The facial segment at highest risk is S1 (the lateral forehead extending into the scalp), and involvement of multiple segments increases the risk of PHACE syndrome. An infantile hemangioma on the mandible could be a marker for a laryngeal hemangioma and referral to ENT could be considered especially in the setting of stridor. According to Dr. Kirkorian propranolol treatment has been shown to be safe in patients with PHACE, however, an echocardiogram should be obtained before starting to evaluate for coarctation of the aorta. Propranolol should be administered three times daily with feeds at the lowest effective dose and concomitant use of topical timolol should be avoided. Propranolol has no effect on congenital hemangiomas or port wine stains.

While small infantile hemangiomas not located in “special sites” have a good prognosis, with 90% involution by age 9, large infantile hemangiomas or those in high-risk locations should be treated aggressively. This is because rapidly growing vascular tissue can damage structures such as cartilage or breast, or pose a risk of facial disfigurement. There can also be a risk to vision if there is occlusion of the visual axis or pressure on the eye.

Dr. Kirkorian identified these “special sites” as:

-

- Ears

- Eyes

- Lips

- Nose

- >1cm on the face

- >2cm on the scalp or body

- steep step off to adjacent tissue

- breast in a female infant

She also emphasized infantile hemangiomas with a steep step off to adjacent tissue are at risk to have significant fibrofatty residue later requiring corrective surgery. In female infants, breast hemangiomas have a risk of causing breast hypoplasia during development and also need special consideration. These “high risk” hemangiomas are noted in an important Clinical Practice Guideline published in Pediatrics (Krowchuk, D. et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019)

With these high-risk infantile hemangiomas, the clock is ticking. Dr. Kirkorian stressed they need treatment before they have significant damage to structures or ulceration. According to pediatric guidelines, these babies should be referred by one month old to a specialist. It is imperative they are evaluated within two weeks of referral to Dermatology due to the high rate of growth early in life. Please consider working young babies with hemangiomas into your schedule urgently if possible, reminded Dr. Kirkorian.

What about treatment in COVID times? Dr. Kirkorian feels it is safe to use propranolol in healthy full-term babies over five weeks old using telemedicine. (Frieden, I. J. et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020).

Now back to congenital hemangiomas. Again, these are fully formed vascular tumors the baby is born with due to somatic mutations in GNAQ or GNA11. They typically present as blue nodules with a striking ring of parlor. Congenital hemangiomas are classified by their involution: rapidly involution congenital hemangioma (RICH), partially involuting congenital hemangioma (PICH), or non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH). Dr. Kirkorian reminded us that propranolol has no treatment role with these tumors, and they are glut-1 negative. Management options are limited to excision or observation.

In babies with a vascular tumor and profound thrombocytopenia, tufted hemangioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma should be considered. These are vascular malformations associated with risk of Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, a consumptive coagulopathy that can be life-threatening. Kasabach-Merritt syndrome should be managed by experts in vascular anomalies at a children’s hospital; first-line treatment of choice today is systemic sirolimus.

Other vascular anomalies that can be seen include venous malformations, blue and purple nodules that bulge with crying or the Valsalva maneuver, and lymphatic malformations. These can be treated with sclerotherapy, excision, or medical management. Evaluation and treatment for these rarer vascular malformations generally should be approached through a Vascular Anomalies Clinic as they often require multidisciplinary care.

What are some scary mimickers of infantile hemangiomas? Dr. Kirkorian reminds us acute myelogenous leukemia, metastatic neuroblastoma, pediatric dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and infantile myofibroma have been reported as congenital blue vascular nodules. Ultrasound can be helpful to determine if there is high flow in the lesion which would be consistent with infantile hemangioma. If the mass is solid, it needs a biopsy.

Dr. Kirkorian’s spotlight on these hot topics in pediatric dermatology provided great insight, and her expertise was welcomed. What a way to kick off the first night of ODAC 2021!

This information was presented by Dr. Yasmine Kikorian at the 2021 ODAC Virtual Conference held on January 14-17, 2021. The above highlights from her lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Edita Newton, second-year dermatology resident at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Clinical Images courtesy of Derm In-Review and the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on medical dermatology topics here.