Authors Adam J. Friedman MD, Kimia Momeni BS, and Mikhail Kogan MD present a case of a young man with psoriasis managed with topical cannabinoids.

Introduction

Case

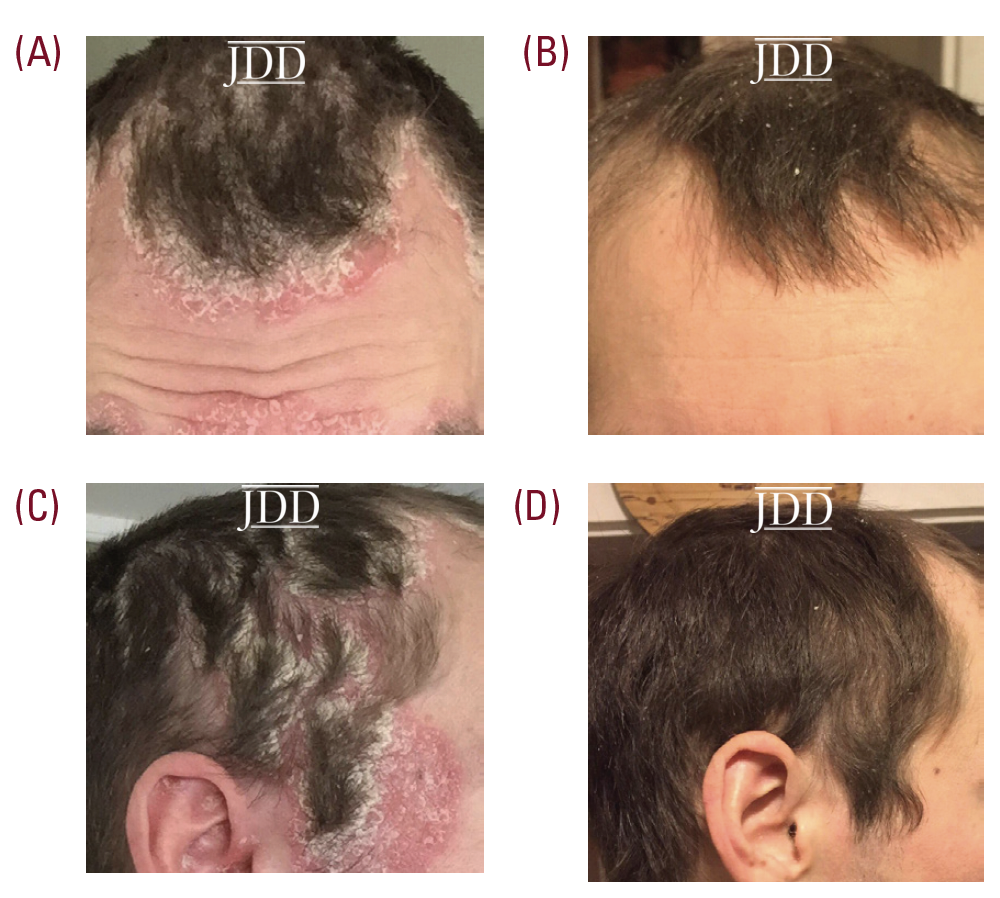

A 33-year-old male patient, with no significant past medical history, presented with a one-year history of psoriasis. Of note, he reported a strong family history of psoriasis with his sister and his father. Disease course began two years prior to diagnosis with erythematous, scaly plaques in sebaceous areas, which progressively worsened (Figures 1A and 1C); he tried over-the-counter topical hydrocortisone steroid cream that failed to control his symptoms. The patient saw his primary care physician who prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. This appeared to reduce erythema on the patient’s face, but for only a short time and the disease spread to his trunk and other areas of his body. Upon follow up, apremilast was recommended, however, he was uninterested only because of cost and side effect profile and wished to pursue a natural approach. After reviewing the pros and cons of utilizing topical medical cannabinoids, the patient was provided with samples of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) distillate cream with medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil, beeswax, and sunflower lecithin, THC soap infused with a scent-free hemp soap, 5 mg/mL, and a hair oil with THC distillate dissolved into jojoba oil, 5 mg/mL. The patient was advised to apply the cream and oil to patches on body skin and to use the oil on the hair-baring areas daily as well as to use the soap when showering. The patient reported improvement within two days of initiating this regimen. Following 2 weeks of use, the patient reported continued improvement and clearance (Figures 1B and 1D). Two months after beginning treatment, the patient’s wife reported that he was only using the products once a week at the first sign of a flare, saying that the symptoms resolved quickly, and he did not require further medication for the next week.

Seven months after initial use, the patient reported that he continues to use the products regularly for maintenance; he uses the soap to prevent activity of areas with high density of hair follicles and follows up with the creams every few days to control skin dryness.

Discussion

As cannabis has become increasingly legalized and decriminalized across the United States, research has expanded, thought not at the same rate as its over the counter commercialization. Cannabis was shown to have therapeutic benefits for conditions such as chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, fibromyalgia, nausea, anorexia, and epilepsy.2,4 In recent years, preclinical research elucidating the biological mechanisms supporting cannabinoid products to treat dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, has increased.3 To better appreciate the preclinical data, the pathophysiology of psoriasis will be reviewed in brief: Psoriasis is characterized by dysregulation of the skin immune system resulting in marked proliferation and keratinization of epidermal cells. Over-activation of Th1 and more importantly, Th17, inflammatory responses in psoriasis produces cytokines like IL-17 and IL-22 that set off cascades of events resulting in increased keratinocyte proliferation, expression of keratins 6 and 16, and inflammatory cell infiltration.4

Through the literature supporting the use of cannabis for the treatment and management of psoriasis is still in its infancy, there is evidence showing that cannabis may be an effective treatment through multiple potential mechanisms. Activation of the endocannabinoid system in the skin reduces inflammation through shifting the pro-inflammatory Th1 response to an anti-inflammatory Th2 response via cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CBr2) activation.5 More specifically, it has been shown that: THC and cannabidiol (CBD)decrease the production and release of proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and interferon (IFN)beta, from lipopolysaccharideactivated microglial cells6; CB2r deficiency in mice results in an exaggerated acute inflammatory response in a dorsal air pouch inflammation mouse model, and conversely, CB2r agonism was also shown to block the endothelial adhesion and transmigration of human neutrophils in a CB2r- dependent manner7; and THC and CBD decrease IL-17 secretion in a dose-dependent manner (at 0.1–5 μM) from MOG-stimulated encephalitogenic T cells in the presence of spleen-derived antigen presenting cells.8

The endocannabinoid system also plays a role in regulating keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, which are pathologically increased in psoriasis. For example, CB1r activation by cannabinoids such as anandamide (AEA) inhibits keratinocyte differentiation and decreases production of keratin K6, a marker of keratinocyte hyperproliferation.9 The potential therapeutic effects of cannabinoids in psoriasis also include activation of non-cannabinoid receptors such as GPR55, which reduces inflammation caused by nerve growth factor, and PPARα and PPARα, which reduces epidermal hyperplasia via suppressed proliferation of keratinocytes.10

This case highlights the need for clinical research in this area. Topical cannabis products are now commercially available for patients in close to two-thirds of the states in US. As more states consider legalization of medical cannabis, likely access and popularity of topical cannabis preparations will increase. While schedule 1 DEA controlled substance significantly restricts clinical research on medical cannabis, reporting similar cases and proceeding with observational studies seems to be the most natural next step. While there is clear consumer, medical practitioner, and industry interest, to date, there is a paucity of FDA approved and narrowly indicated products available.11 More research, investment, and acceptance is needed to fully capitalize on the potential of cannabinoids in dermatology.

Disclosures

References

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017 Jan 12. Available from: https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK423845/ doi: 10.17226/24625

3. Derakhshan N, Kazemi M. Cannabis for refractory psoriasis-high hopes for a novel treatment and a literature review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2016;11(2):146– 147. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574884711666160511150126

4. Eagleston L, Kalani NK, Patel RR, et al. Cannabinoids in dermatology: a scoping review. Dermatology Online Journal. 2018;24(6). June 15, 2018

5. Cabral GA, Griffin-Thomas L. Emerging role of the cannabinoid receptor CB2 in immune regulation: therapeutic prospects for neuroinflammation. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e3

6. Kozela E, Pietr M, Juknat A, Rimmerman N, Levy R, Vogel Z. Cannabinoids Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol differentially inhibit the lipopolysaccharide- activated NF-kappaB and interferon-beta/STAT proinflammatory pathways in BV-2 microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;15;285(3):1616-26.

7. Kapellos TS, Taylor L, Feuerborn A, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 2 deficiency exacerbates inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. FASEB J. 2019.;33(5):6154-6167

8. Kozela E, Juknat A, Kaushansky N, Rimmerman N, Ben-Nun A, Vogel Z. Cannabinoids decrease the th17 inflammatory autoimmune phenotype. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8(5):1265-76.

9. Maccarrone M, Di Rienzo M, Battista N, et al. The endocannabinoid system in human keratinocytes: evidence that anandamide inhibits epidermal differentiation through CB1 receptor dependent inhibition of protein kinase C, activating potein-1, and transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33896–903.

10. Sertznig P, Seifert M, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and the human skin: importance of PPARs in skin physiology and dermatologic diseases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:15–31.

11. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA and Cannabis: Research and Drug Approval Process. Washington, D.C. 2020.

Source

Friedman, A. J., Momeni, K., & Kogan, M. (2020). Topical cannabinoids for the management of psoriasis vulgaris: report of a case and review of the literature. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 19(8), 795.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this case report? Find more here.