The numbers are staggering when it comes to the management of skin cancer in the United States and worldwide. Signs of chronic exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun and/or indoor tanning bed use include solar lentigines, hyperpigmentation, wrinkles and pre-cancerous lesions called actinic keratoses. Actinic Keratoses (AKs) best identified as scaly, pink macules and papules, result from long-term UV radiation exposure. Actinic Keratoses have a strong predilection for sun exposed skin such as the head, neck, ears, hands, and upper extremities. While the data is conflicted, risk for AKs to acquire sufficient mutations to progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with the potential to become an invasive form of the disease, ranges from 0.025-20% per actinic keratosis.¹

About 38% of Caucasians over the age of 50 have at least one AK in the United States. The high burden of disease costs about 920 million dollars per year and likely this number does not factor in every aspect of the evaluation, treatment, and potential complication of the disease.²

During the 2022 ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic and Surgical Conference, Dr. C. William Hanke provided a comprehensive overview on the burden of disease and treatment options for actinic keratoses. His talk highlighted an important 2019 single-blinded, randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) for the treatment of actinic keratoses. Of the four treatment options available to the patient population, ingenol mebutate gel and methyl amniolevulinate photodynamic therapy (MAL-PDT) are not available in the United States. Of the two other treatment options, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 5% cream and imiquimod 5% cream, there is equitable adherence of about 88 percent and cosmetic results of 90 percent in both groups. However, the cumulative probability of treatment success was higher in the 5-FU cohort of about 75 percent versus 54 percent in the imiquimod group. The authors’ concluded 5-FU is the first line, most cost-effective treatment for diffuse AK burden in the head and neck region at the 12-month follow-up.³

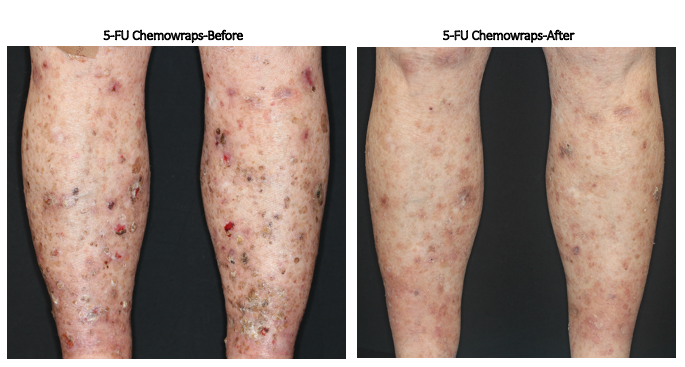

Of note, Dr. Hanke’s clinical expertise has led to the use of 5-FU under occlusion with weekly “chemo wraps.” This process is completed in the clinic setting for extensive actinic damage of the upper and lower extremities. The images below highlight use of an Unna boot to achieve 5-FU under occlusion with dressing changes occurring in the office on a weekly basis for two to four weeks based on need and clinical response. The second image is notable for the pre- and post-treatment with 5-FU chemo wraps for the lower extremities. The images are notable for its highly effective reduction of actinic burden.

Another treatment option would be to combine Calcipotriol and 5-FU for synergistic effects that allow for a shorter treatment duration of twice per day application for 4 days. While there is more of an inflammatory response, inflammation peaks at day 10 and usually resolves within 2 weeks. Unfortunately, 5-FU alone cannot achieve the same degree of significant reduction in complete or partial AK reduction when used for 4 days only when compared to the combination therapy of Calcipotriol and 5-FU.4

As of December 2020, tirbanibulin 1% ointment, a microtubule inhibitor, was approved for management of AKs with a once daily application for 5 days. There was a 44-54% complete clearance on the face and scalp and a 72% partial clearance when reevaluated post-treatment on day 57. However, this new medication is extremely costly with the lowest GoodRx pricing nearing one thousand dollars.5

As a big proponent of photodynamic therapy (PDT), Dr. Hanke makes a strong case for its use in photo-rejuvenation, reducing AK burden and even possibly for curing superficial SCCs and basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Photosensitizing drug + Light source = Cellular Destruction

Photosensitizers that are approved in the United States includes 5-aminolevulinic acid (10% and 20% formulations of 5-ALA) to be used with Blu-U, IPL, PDL, or 633 nm red LED. The mechanism of action of PDT is the following:

ALA uptake by cells ⇒ALA converted to protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) ⇒PpIX activation by intense light ⇒ cell necrosis/death

While advances have been made with PDT, there are some elements of this treatment protocol to keep in mind:

-

- Incubation time for ALA application (15-60 minutes)

- Pain

- Down time or recovery (at least 2-3 days)

As Dr. Hanke eloquently stated in his lecture, there is a ‘symphony of variables’ that contribute to PDT’s efficacy, including:

-

- Incubation time of ALA

- Length of light exposure

- Type of photosensitizing drug

- Type of light source (blue, red, laser, IPL, daylight, white light LED)

- Occlusion time (extremities only)

- Distance of light source from target

- Cooling (pre-op, intra-op, and post-op)

- Curettage (pre-treatment for hyperkeratotic lesions)

- Pre-treatment with 5-FU +/- calcipotriol, imiquimod, tretinoin)

- Pre-treatment with microneedling, fractionated laser or microDA

- Use of H1 antihistamines (post-op symptom relief)

- Number of treatment sessions

- Skin temperature during treatment

- Skin preparation technique

Also noted in Dr. Hanke’s lecture were smaller case series and studies performed that determined the efficacy of red light PDT with 10% ALA for AKs and SCC in situ (SCCis) on the trunk and extremities. For the AK burden on the neck, extremities, and trunk there was a 67% complete clearance and in a one-year follow up only 14% recurrence rate. In the SCCis study, all 12 patients had biopsy proven superficial malignancy with a mean diameter of 1.83 centimeters (cm). The 10% ALA was applied for 3 hours, and each patient had 1-2 PDT treatments about 10 days apart. At the end of the study’s 4-week follow-up every patient had clinical and histologic clearance.6

Another noteworthy takeaway from Dr. Hanke’s lecture included a head-to-head study for the use of 10% ALA gel versus 20% ALA solution with blue light therapy. With a one-hour incubation time with the topical medication and exposure to blue light for 15 minutes, this led to significant reduction in AK burden on the face and scalp after the completion of just two treatments. Of note, the 20% ALA solution led to greater local skin reactions when compared to the 10% ALA gel. This maybe a consideration for individuals with very sensitive skin.7

Given the significant burden of non-melanoma cutaneous cancer (NMSC), PDT treatment was trialed for the treatment of biopsy proven superficial type basal cell carcinoma. The European study, conducted in 2018, studied 10% ALA versus MAL with four PDTs treatments over the course of 12 weeks and a one year follow up. For the ALA arm of the study, there was a 72-95% lesion clearance with less than 10% recurrence rate.8

Though these findings are promising the significantly increased time burden of the PDT treatment method for NMSC should be noted when comparing to standard therapies such as excision or electrodesiccation and curettage.

Dr. Hanke’s extensive and detailed lecture provided clarity and therapeutic options for the treatment of AKs in nearly every patient population. Furthermore, his talk delved in the nuances of PDT treatment for superficial type non-melanoma skin cancers. As with any treatment option, it is important to consider patient’s demographics, co-morbidities, risk factors, pain or discomfort tolerance and ability for short and long-term follow up. I hope the readers of this post can appreciate that not only is the burden of UV radiation exposure high but that there are a myriad of effective treatment modalities.

References

-

- Quaedvlieg PJ, Tirsi E, Thissen MR, Krekels GA. Actinic keratosis: how to differentiate the good from the bad ones?. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(4):335-339.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(2):350-358. doi:10.1111/bjd.14852

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized Trial of Four Treatment Approaches for Actinic Keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(1):106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 Trials of Tirbanibulin Ointment for Actinic Keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(6):512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Cervantes JA, Zeitouni NC. Photodynamic therapy utilizing 10% ALA nano-emulsion gel and red-light for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in-situ on the trunk and extremities: Pilot study and literature update. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2021;35:102358.

- Nestor MS, Berman B, Patel J, Lawson A. Safety and Efficacy of Aminolevulinic Acid 10% Topical Gel versus Aminolevulinic Acid 20% Topical Solution Followed by Blue-light Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis on the Face and Scalp: A Randomized, Double-blind Study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(3):32-38.

- Morton CA, Dominicus R, Radny P, et al. A randomized, multinational, noninferiority, phase III trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BF-200 aminolaevulinic acid gel vs. methyl aminolaevulinate cream in the treatment of nonaggressive basal cell carcinoma with photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):309-319. doi:10.1111/bjd.16441

This information was presented by Dr. C. William Hanke at the 2022 ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic and Surgical Conference held January 14-17, 2022. The above highlights from his lecture were written and compiled by Dr. Freba Farhat.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Medical Derm here.