Tomorrow when we arrive into clinic (or this afternoon if you are reading this during your lunch break), we will invariably be greeted with patients who struggle with one of the most common diseases we treat – acne. More than likely, we will reach for topical retinoids, topical antibiotics, and the occasional systemic antibiotic. Evidence supports the short-term use of systemic antibiotics to gain control of acne and help our topical regimens overcome the disease process. Yet, in an era when concerns of antibiotic resistance are ever-present and our knowledge of the microbiome is ever-increasing – are we doing the right thing? How can we be stewards of proper antibiotic use in light of resistance concerns while simultaneously bringing out the best skin for our patients?

During the 2020 GW Virtual Appraisal of Advances in Acne Conference, Dr. Neal Bhatia, Director of Clinical Dermatology at Therapeutics Clinical Research in San Diego, CA, helped us fine-tune our use of these effective, but sometimes misused, elements of our armamentarium against acne. In his lecture, Use of Antibiotics in Acne, Dr. Bhatia displayed his eminent ability to breakdown important research and guidelines to help us answer clinically relevant questions.

This review will provide an overview of his talk, including:

-

- Discussion of the American and European guidelines on the treatment of acne – focusing on where systemic antibiotics fit in and alternatives to their use

- Breakdown of recent studies, including anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline vs standard dose, new formulations of minocycline, and sarecycline pivotal trials

- Tips on when and how to use oral antibiotics in a concerted effort to treat acne

Before we get into the full review, here are my “practice barometers” – what I took away from the lecture that may change my practice or confirm my standards:

![]() Consider anti-inflammatory dose antibiotics, photodynamic therapy, hormonal therapies, and other adjuncts in a patient who needs longer-term control, but is not a candidate for isotretinoin

Consider anti-inflammatory dose antibiotics, photodynamic therapy, hormonal therapies, and other adjuncts in a patient who needs longer-term control, but is not a candidate for isotretinoin

![]() Re-evaluate acne patients at 6-8 weeks after starting oral antibiotics to assess the efficacy

Re-evaluate acne patients at 6-8 weeks after starting oral antibiotics to assess the efficacy

![]() Continue with a low threshold for isotretinoin in patients resistant to topicals

Continue with a low threshold for isotretinoin in patients resistant to topicals

![]() Consider sarecycline as anti-inflammatory antibiotic for use in acne

Consider sarecycline as anti-inflammatory antibiotic for use in acne

Let’s start this off with a question

Per capita, what specialty writes the greatest number of oral antibiotic prescriptions? Answer: dermatologists. It should be no surprise that the majority are in the tetracycline class. These tetracyclines have multiple effector points on the pathogenesis of acne – but how? Prior to comedogenesis, there are elevated inflammatory markers in uninvolved skin of patients with acne (increased CD4+ T-cells, increased macrophages, follicular IL-1 expression, aberrant integrin expression). So, what comes first, the comedone or the inflammation? Note, a similar discussion is occurring in hidradenitis suppurativa. Either way, tetracyclines are able to inhibit the activation or impact of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), kallikrein 5 (KLK5), and human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 (hcap18) which lead to inflammation in acne lesions. In that light, maybe our script pads are being used correctly!

When to consider non-tetracycline antibiotics

I am sure we have all considered, or even prescribed, other antibiotics for treatment of acne. Each comes with advantages and disadvantages.

-

- Azithromycin is well tolerated, and relatively safe in pregnancy. But some studies show an increased risk of miscarriage

- TMP-SMX has well-known issues, including allergy and severe cutaneous adverse reactions, but treatment can be a great success in some patients

- Amoxicillin also comes with allergy baggage, but can be considered for a pregnant patient and may have a lower cost

- Cefalexin is commonly used by our surgical colleagues and is helpful in treatment of skin infections with low clinical concern for MRSA, but will use of this for acne result in increased antibiotic resistance?

- Minocycline, and then doxycycline, is better at reduction of C. acnes when compared to TMP-SMX and erythromycin

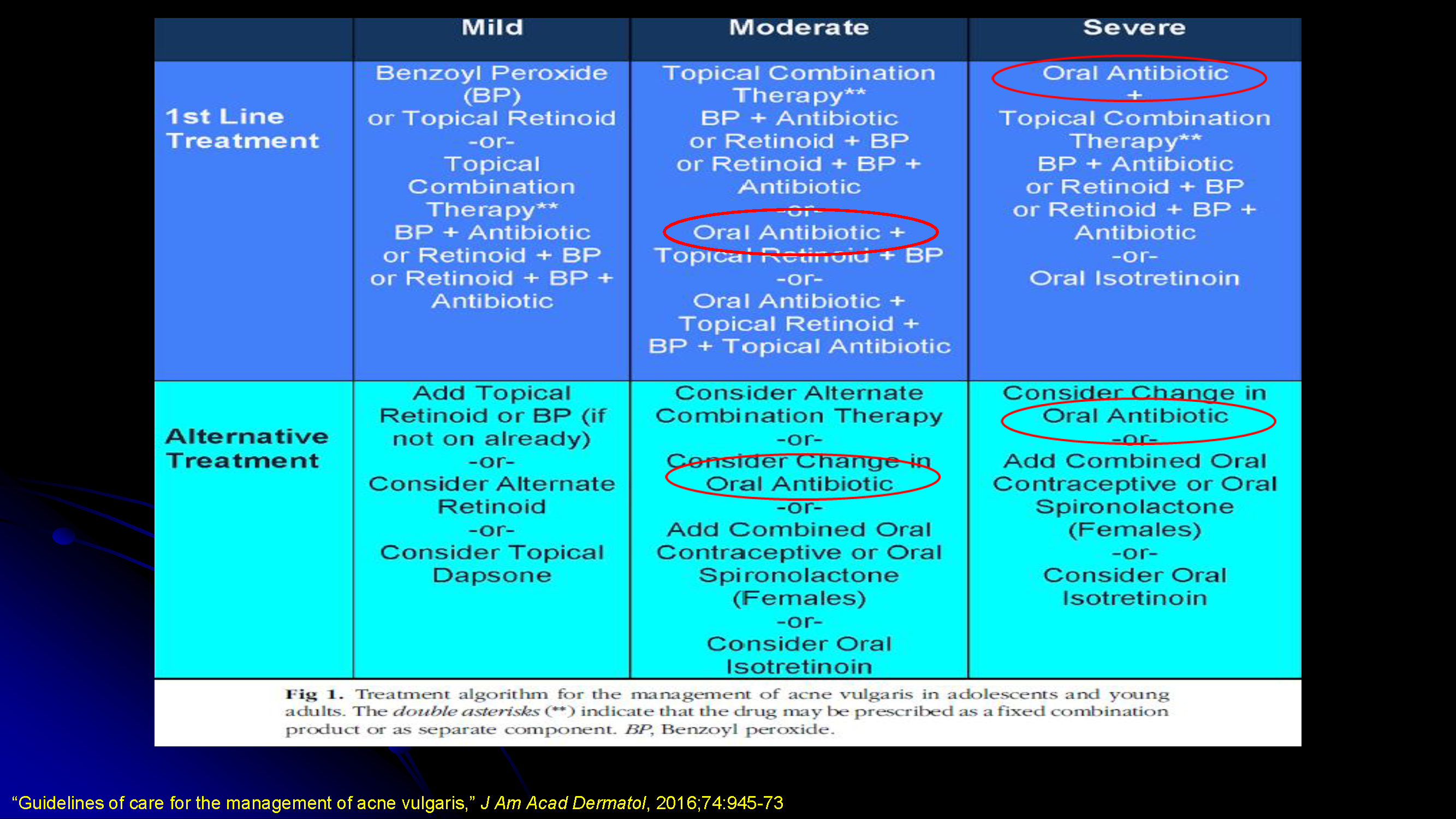

Review of the treatment guidelines

Guidelines and consensus statements in the JAAD support the use of systemic antibiotics in patients with moderate to severe acne – but only when used with the right patient1,2. The following are considerations in determining whether systemic antibiotics are appropriate:

-

- Assess risk-benefit ratio to balance patient need and public interest in maintaining effective antibiotics (i.e. reduce resistance to antibiotics)

- Oral antibiotics should only be used when topicals are failing and/or acne is extensive (i.e. trunk)

- Efficacy of doxycycline and minocycline are considered comparable

- Other forms of systemic antibiotics should be limited to those patients who cannot tolerate tetracycline-class antibiotics or in which use is contraindicated (i.e. pregnant patients or children below age 8)

- Consider macrolides first (azithromycin and erythromycin) before TMP-SMX, penicillins, or cephalosporins

- Benzoyl peroxide and/or retinoids should be used in combination with systemic antibiotics for a more comprehensive management and to help get patients off antibiotics more rapidly

- Avoid oral and topical antibiotics as monotherapy (rapid development of resistance)

- Evaluate response to oral antibiotics at 6-8 weeks and limit use to 3-4 months

- Consider anti-inflammatory dosing to minimize potential for resistance

Anti-inflammatory dosing

So, it seems we are prescribing the right medicine. But do we use a low dose? Regular dose? Dr. Bhatia presents a study that shows slightly better results with inflammatory lesion counts when treated with doxycycline 40mg modified-release as opposed to the traditional doxycycline dosed at 100mg daily in patients with moderate to severe acne3. Use of this dosing may be preferable as:

-

- GI side effects and sun sensitivity were reduced

- The 40mg dose is below the antimicrobial level which may reduce resistance issues

- From a side effect standpoint, while the study does not mention if doxycycline hyclate or monohydrate was used, it was clear that the low-dose regimen had fewer side effects overall

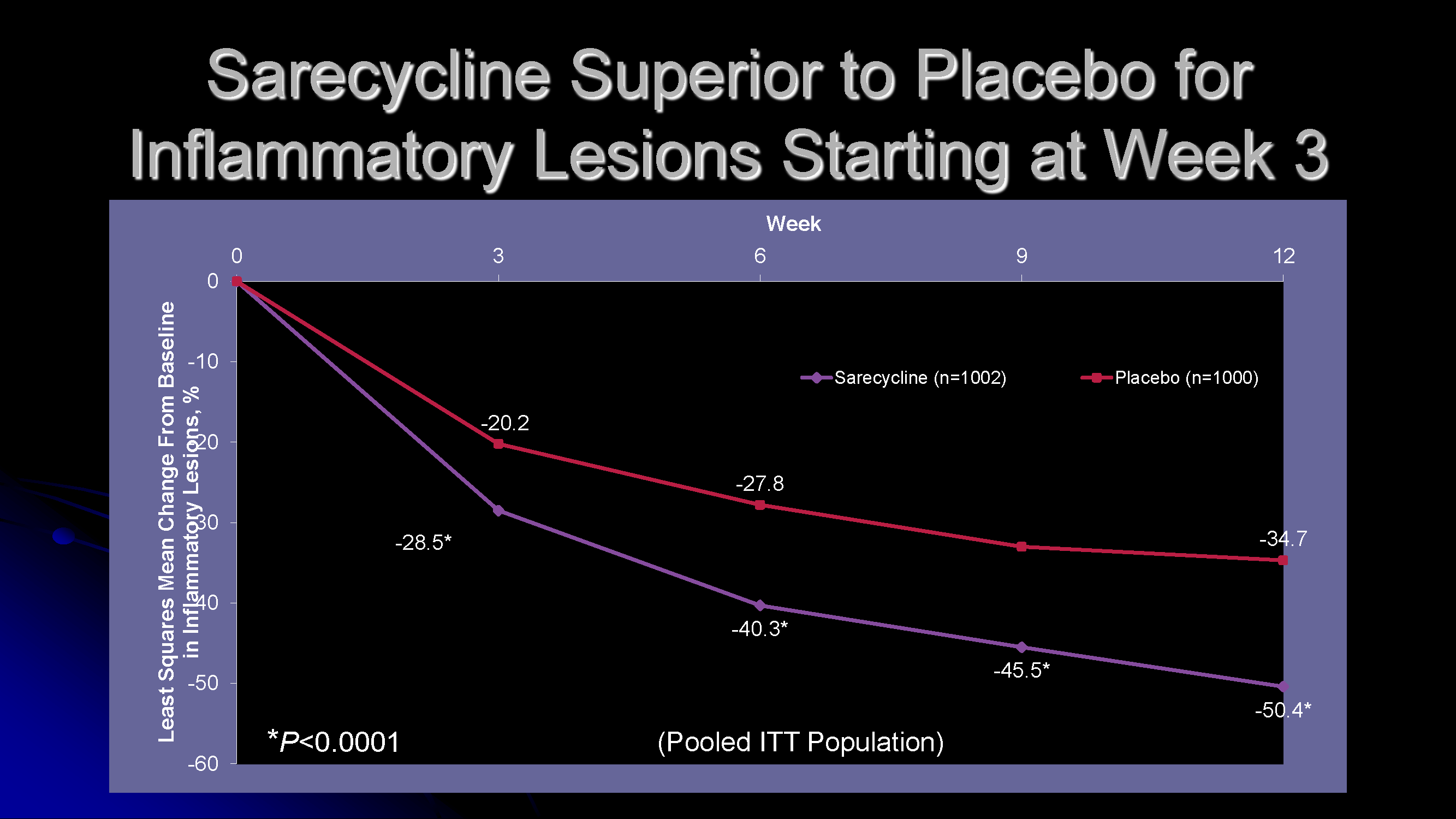

What’s new in antibiotics for acne? Sarecycline.

Here’s a breakdown of this new medication and the two Phase 3 studies that brought it to approval.

-

- Approved for ages 9 and up – once daily weight-based dosing, can be taken with or without food, and has good anti-inflammatory activity

- Similar adverse event warnings to other tetracyclines – teeth staining before 8 years of age, increased intracranial pressure, pseudomembranous colitis

- Studies – participants 9-45 years of age, moderate or severe acne (IGA 3 or 4), 20-50 inflammatory lesions, ≤100 non-inflammatory lesions, ≤ 2 nodules, 1.5mg/kg/day, once-daily dosing, 12-week study vs placebo. 60mg, 100mg, and 150mg tablets.

- Continuous, steady improvement to 12-week end of study, primary end-point: ≥2-grade improvement and IGA of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear)

- Non-inflammatory lesions counts were also noted to be improved compared to placebo

Other important pearls:

-

- Important to optimize combination of topicals and hormonal control when using systemic antibiotics

- Rifampin is the only antibacterial that reduces efficacy of oral contraceptives

- Doxycycline – monohydrate has less GI side effect vs. hyclate (but typically more expensive)

- Doxycycline vs. minocycline:

- Doxycycline – more GI side effects, sun sensitivity, and vaginal candidiasis

- Minocycline – longer duration side effects – hyperpigmentation, drug-induced lupus, etc.

- Tips to reduce doxycycline side effects:

- Take tablet with glass of water and food

- Remain upright for a few hours after dose and do not take immediately before bedtime

- Advise stringent sun protection

- Avoid dairy, metal ions, vitamins, and fortified cereals within 3 hours of dose

- Minocycline:

- Advantages – lipophilic, better reduction of C. acnes, unaffected by dairy

- Disadvantages – need to weight base dose, headache, vertigo, drug-induced lupus, pigmentation (increased risk with: 200mg/day or 50 gram total dose)

- Minolira (new version of minocycline) – reaches maximum concentration faster than Solodyn when taken with or without food

Final Thoughts

-

- Avoiding antibiotics in the treatment of acne, if possible, is a good thing

- Consider: Do you need antibiotics? What is your exit strategy?

- When do you reach for oral antibiotics? Which one do you use and why? How do you fight antibiotic resistance? What alternatives do you use to oral antibiotics?

Please share your comments and join the discussion at the end of this post, and on Instagram @nextstepsinderm!

This information was presented by Dr. Neal Bhatia at the GW Virtual Appraisal of Advances in Acne Conference held July 30th, 2020. The above highlights from his lecture were written and compiled by Dr. James Contestable, staff dermatologist at Naval Medical Center Camp Lejeune. Images of slides courtesy by Dr. Neal Bhatia

Clinical images of acne patients used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

References

-

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jun;82(6):1576]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-73.e33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

- Thiboutot DM, Dréno B, Abanmi A, et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians: An international consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2 Suppl 1):S1-S23.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.078

- Moore A, Ling M, Bucko A, Manna V, Rueda MJ. Efficacy and Safety of Subantimicrobial Dose, Modified-Release Doxycycline 40 mg Versus Doxycycline 100 mg Versus Placebo for the treatment of Inflammatory Lesions in Moderate and Severe Acne: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Controlled Study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(6):581-586.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The author is a military service member.

Did you enjoy this article? Find more on Medical Dermatology here.