Pediatric lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a clinical variant of lichen planus (LP) that can lead to scarring hair loss without prompt intervention. While various therapies exist, intralesional and topical corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment in pediatric LPP. Refractory cases may require systemic therapies, selection of which may prove challenging due to the lack of data regarding pediatric disease and effective treatment regimens. The objective of this case study is to present a new instance of pediatric LPP and identify all reported cases of pediatric LPP with an emphasis on treatment and response.

INTRODUCTION

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory papulosquamous dermatosis occurring in children in only 10–11% of cases.1Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a clinical variant of LP that demonstrates lymphocytic scarring alopecia.2 It is relatively uncommon in children, accounting for only 6.3% of reported childhood LP cases.3 Clinically, centrifugally growing plaques favoring the parietal and/or occipital scalp with perifollicular scaling and absence of follicular ostia are accompanied by pruritus and hair loss.2

Treatment for LPP poses a challenge for dermatologists. While several treatments are available and have indeed demonstrated clinical value, varying levels of patient improvement with these regimens suggests that the treatment algorithm for LPP is still largely undetermined.3

We describe a case of LPP in an African American adolescent treated with pioglitazone, accompanied by a literature review of published LPP cases in the pediatric population.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 15-year-old African American male with history of atopy, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and prediabetes who presented to dermatology clinic for a five-year history of scarring alopecia initially manifesting as pain, pruritus, and scale. Treatments prior to presentation included clobetasol 0.05% foam daily to the scalp with minimal improvement. Patient’s medications for his additional comorbidities included methotrexate, etanercept, and metformin.

Physical exam revealed perifollicular plugging and erythema of the lateral eyebrows and posterior vertex scalp along with scarring of the anterior vertex scalp evidenced by absence of follicular ostia (Figure 1). Biopsy was deferred as physical exam and dermoscopy findings were consistent with LPP. He was initiated on clobetasol 0.05% foam daily to involved areas of the scalp, tacrolimus 0.1% ointment daily to the brows and face, and doxycycline monohydrate 100 mg twice daily. In addition, he received intralesional Kenalog (ILK) injections to the affected scalp and eyebrows.

Improvement was appreciated at his four-month follow-up visit and he was continued on his initial treatments and additional ILK injections were performed. At follow-up two months later, active disease was still present as evidenced by erythema and perifollicular plugging of the vertex scalp, so a third round of ILK injections was administered, and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily was added to his regimen.

The patient showed consistent improvement over the next 8 months, as evidenced by eyebrow regrowth and the appearance of nascent hairs at the vertex scalp as well as a lack of perifollicular erythema and scale. The patient’s treatment regimen was subsequently maintained, and ILK injections were deferred. Four months later he began endorsing scalp pain and pruritus, and physical exam revealed spread of perifollicular erythema and worsening alopecia (Figure 2).

Regression in the patient’s condition prompted evaluation of an additional treatment to assist in controlling his disease. The addition of pioglitazone, a PPAR‐γ agonist, was considered. The persistence of progressive inflammation and hair loss in conjunction with the patient’s diagnosis of prediabetes formed the rationale for the use of pioglitazone in treatment of the his LPP. After discussion with his endocrinologist, pioglitazone (15 mg daily for three months followed by 30 mg daily for three months) was added to his regimen.

At his follow-up visit five months later, patient admitted to inconsistent use of pioglitazone but noted improvement in scalp symptoms. He tolerated the treatment without adverse effects. Physical exam revealed active but stable disease (Figure 3).

Discussion and Review of the Literature

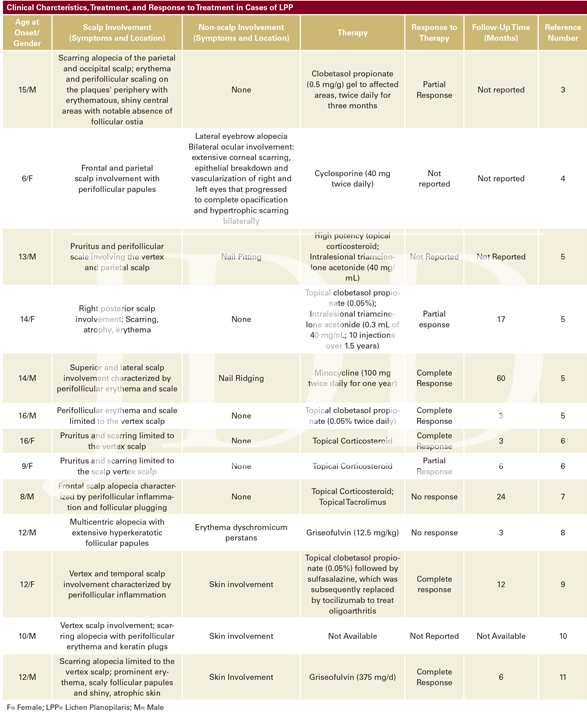

We conducted a literature review analyzing 13 cases of pediatric LPP, with particular emphasis on treatment and response to treatment. The review was conducted using the UAB School of Medicine library databases, limiting the search to articles containing the keywords “lichen planopilaris” and “pediatric.” We included only cases that were able to provide the following epidemiological data: age, gender, initial therapy, response to therapy and the duration to follow-up. Cases unable to meet these criteria were excluded. In addition, while some degree of scalp involvement was required for inclusion, non-scalp involvement was also noted and included skin, nail and/or ocular involvement (7 patients).

Table 1 provides an overview of 13 pediatric LPP cases focusing on clinical presentation, treatment, and their response to therapy. Response to therapy was designated as partial, complete or no response. These classifications were created to distinguish between the degree of resolution of lesions and tendency for recurrence. “Complete response” was assigned to patients whose lesions completely resolved without recurrence, whereas “partial response” was allocated to those who reported either improvement in the size/appearance of lesions and/ or improvement in symptoms. “No response” was assigned to patients who did not note any improvement in size/appearance of lesions, nor any improvement in symptoms. Follow-up time was recorded in months and included the entire reported duration of treatment and clinic visits.

Table 1 demonstrates that treatment for LPP remains varied, particularly in regard to use of systemic agents. While a number of therapies have been shown to be reasonably efficacious, a concise treatment algorithm for this disease remains a clinical challenge.3 Currently, treatment for LPP in children includes corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, systemic), tetracyclines, calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, cyclosporine), and antifungals (griseofulvin).

According to our review, 83% of pediatric patients treated with intralesional and/or topical corticosteroids achieved partial or complete response, suggesting a significant role for corticosteroids in treatment of pediatric LPP. These findings are supported by similar results obtained from two separate studies.3,11 Racz and colleagues’ systematic review of treatment options for LPP, although not limited to the pediatric population, demonstrated a 76% partial or complete response to high- or medium-potency topical corticosteroids.11 In addition, a review conducted in 2018 analyzing 11 cases of pediatric LPP and their respective treatments showed 80% of patients with scalp-limited LP achieving either partial or complete response to treatment with topical and/or intralesional corticosteroids.3 These findings, while promising, indicate that a percentage of patients do not adequately respond to topical and/or intralesional steroids, necessitating the escalation to other topical agents or systemic therapies.

Several systemic agents with varying degrees of efficacy exist. Treatment with topical and/or intralesional corticosteroids without additional immunomodulatory therapy was used in 6 cases of scalp-limited LPP. Of these, 3 cases resulted in partial response (50%) and another 2 in complete response (33.33%). The 6th case utilized a high potency topical corticosteroid and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, however the response was not reported (16.67%).

An additional 7 cases of scalp-limited LPP were reviewed, only 6 of which reported the therapy regimen used. Of these 6 cases, two utilized griseofulvin in the treatment plan. When griseofulvin (12.5 mg/kg) was utilized alone, no response when achieved. However, when used (375 mg/d) in conjunction with prednisone (20 mg/d) or topical betamethasone dipropionate a complete response was achieved. The remaining 4 cases reviewed used either antibiotics, immunomodulatory therapy other than corticosteroids or a combination of corticosteroids and immunomodulatory therapy. Those reporting complete response used minocycline (100 mg twice daily) or topical clobetasol propionate (0.05%) followed by sulfasalazine. No response was achieved in patients utilizing topical corticosteroids in addition to topical tacrolimus, and no response was reported for the use cyclosporine (40 mg twice daily).

Novel therapeutic options for pediatric LPP are being explored. Pioglitazone, a PPAR-γ agonist with a favorable side effect profile, has demonstrated both a theoretical benefit in LPP as well as promising results in affected adults.12-16 There are scant data evaluating the efficacy of pioglitazone in children with LPP; however, its successful use in adults could suggest pioglitazone’s potential benefit in pediatric patients.

CONCLUSION

LPP is a lymphocytic scarring alopecia characterized clinically by centrifugally growing plaques favoring the parietal and/or occipital scalp accompanied by perifollicular scale, pruritus, and tenderness. Clinical improvement in treatment of LPP in children has been achieved with several treatment regimens, including topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids, tetracyclines and antifungals such as griseofulvin. Per our review 83% of patients with scalp-limited LPP saw either partial or complete response to of their condition with topical and/or intralesional corticosteroids, suggesting a strong role for these treatment regimens in LPP.

While intralesional and topical corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment in pediatric LPP, resistant cases requiring systemic therapies pose a challenge due to the lack of data regarding pediatric disease. In our patient, lack of adherence with pioglitazone made evaluation of medication efficacy difficult. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of systemic agents in pediatric LPP.

DISCLOSURES

Consent statement: Informed consent to publish photographs was obtained from the parent.

REFERENCES

2. Góes HF, Dias MF, Salles SN, et al. Lichen planopilaris developed during childhood. Anais Brasileiros De Dermatologia. 2007;92(4):543–545

3. Bevans S, Theos A, Fowler P, et al. Pediatric ocular lichen planus and lichen planopilaris: One new case and a review of the literature. Pediatric Dermatology. 2018;35(6):859-863.

4. Christensen KN, Lehman JS, Tollefson MM. Pediatric lichen planopilaris: clinicopathologic study of four new cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):621-27.

5. Chieregato C, Barba A, Zini A, et al. Lichen planopilaris: report of 30 cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol.2003;42:342.

6. Abbasi NR, Orlow SJ. Lichen planopilaris noted during etanercept therapy in a child with severe psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:118.

7. Metin A, Calka O, Ugras S. Lichen planopilaris coexisting with erythema dyschromicum perstans. Br J Dermatol.2001;145:522-23.

8. Jayasekera, PS, Walsh ML, Hurrell D, et al. Case report of lichen planopilaris occurring in a pediatric patient receiving a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor and a review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016; 33(2):e143-6.

9. Sehgal VN, Bajaj P. Lichen planopilaris. Int J Dermatol.2001;40:516-17. γ

10. Sehgal VN, Bajaj P, Srivastva G. Lichen planopilaris [cicatricial (scarring) alopecia] in a child. Int J Dermatol.2001;40:461-63.

11. Racz E, Gho C, Moorman PW, et al. Treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(12):1461-70.

12. Ramot Y, Bertolini M, Boboljova M, et al. PPAR‐γ signalling as a key mediator of human hair follicle physiology and pathology. Experimental Dermatolog. 2019;29(3):312–321

13. Peterson EL, Gutierrez D, Brinster NK, et al. Response of lichen planopilaris to pioglitazone hydrochloride. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(12):1276-1279.

14. Baibergenova A, Walsh S. Use of pioglitazone in patients with lichen planopilaris. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(2):97-100.

15. Mesinkovska NA, Tellez A, Dawes D, et al. The use of oral pioglitazone in the treatment of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(2):355-356.

16. Spring P, Spanou Z, de Viragh PA. Lichen planopilaris treated by the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone: Lack of lasting improvement or cure in the majority of patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):830-832.

Source

Preda-Naumescu, A., Bevans, S. L., & Mayo, T. T. (2021). Pediatric Lichen Planopilaris Treated With Pioglitazone: A Case Study and Literature Review. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD, 20(7), 779-782.

Content and images used with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

Did you enjoy this case report? Find more here.